![]()

1

Arnold Gesell:

The Maturationist

FREDRIC WEIZMANN

York University

BEN HARRIS

University of New Hampshire

Arnold Gesell (1880–1961) was both a psychologist and a pediatrician. From the 1920s to the 1950s, his teaching and writing made him the foremost expert on parenting and child rearing until overtaken in popularity by his successor, Benjamin Spock. Although there is an institute that bears Gesell’s name, his influence today comes not from his students or followers but rather from an idea that he popularized and embedded in the national psyche: the widespread belief that there is a timetable of child development, a set of age-related stages through which infants and children pass, with each stage being characterized by typical behaviors. Although others, most famously Sigmund Freud, had also proposed stage theories of child development, no one had documented or laid out the landmarks of development so precisely or so comprehensively. One still hears parents explain the behavior of their toddler by referring to “the terrible twos,” or talk of a child “passing through a stage,” and parents or professionals still speak of “developmental readiness” or “school readiness.” These were ideas embodied in Gesell’s books, which bore titles such as The Mental Growth of the Preschool Child (1925b) and The Child From Five to Ten (1977).

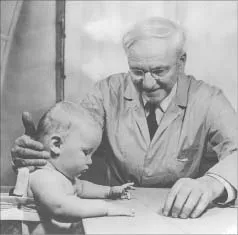

Figure 1.1 Arnold Gesell and infant. (Courtesy of Yale University, Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library. With permission.)

SHAPED BY HIS FAMILY AND ENVIRONMENT

To write about this famous developmentalist, we begin by examining the development of his ideas, which were greatly influenced by his family, community, and schooling. Arnold Gesell was the oldest of five children, raised in a loving, tightknit family. From his family, he developed the talents, work habits, and view of humankind that made him unique as a developmental theorist and researcher.

His father, Gerhard, had a photography business in Alma, Wisconsin, a Mississippi River town so small that it had only two streets. Gerhard documented the life of the town, its environs, and residents in studio portraits and outdoor photos. He pictured social clubs, individuals, and the working life of town and river. Arnold learned from him how to see adults and children in context, in settings that defined their lives and shaped their behavior. Looking at the artfully composed photographs by the father, one is struck by how much Arnold’s theories put each child in a frame consisting of its age, family, and level of maturation.

The young Gesell also learned from his father humanitarian and republican values: As Arnold explained in a funeral oration in 1906, his father “hated all injustice, cruelty and oppression” (Gesell, 1906, p. 2). An orphan who had a “neglected and miserable childhood,” the elder Gesell had come to the United States from Germany as a teenager and enlisted in the Union Army to defend the young republic (Gesell, 1906, p. 3). Having rejected the old world’s reverence for monarchs, Arnold’s father believed that Americans had begun to worship wealth as their new aristocracy. He believed, as did Arnold, that social solidarity and familial love should replace the love of material possessions.

While his father served as the family’s patriarch, Arnold’s mother, Christine, provided youthful energy and a desire for upward mobility. A former school teacher who married at age 18 (her husband was 35), she gave birth to Arnold 9 months later. Among her gifts to Arnold was a love of both learning and teaching. Always the teacher, she demonstrated that anything in life could be turned into a song, a poem, a school lesson, a play, or a family pageant, to be learned and taught—acted out—with a role for everyone.

In today’s parlance, we would say that every day was full of teachable moments for the Gesell family (for a photo of the Gesell family, see Figure 1.2). And Arnold expressed this as an adult, publishing the architectural plans that he made for the bungalow he built in the desert when recovering from tuberculosis (Gesell, 1910). He also published a description of a baby basket he designed and built for train travel after his son was born. Unlike B. F. Skinner’s account of his “Baby in a Box” (Skinner, 1945), Gesell’s article was full of loving details about caring for the baby, both in and out of his invention (Gesell, 1911).

From parents and community, Arnold Gesell also learned to be upright, hardworking, and successful. His responsibilities were part of a vision in which both the individual and society were evolving. With the help of good habits and right living, humans were moving away from selfishness and ignorance toward socialist enlightenment. Consistent with this view, Arnold Gesell came to see each child as shaped by both heredity and environment, with habits and social influences intervening between the two. As Arnold’s family nurtured him and served as a buffer between him and the outside world, so each child’s abilities and habits would change how the world affected him or her. This philosophy, that maturation could be aided by a thoughtfully engineered environment, became one of Gesell’s messages to the world. It also reflected his experience as a child and young adult and was part of the broader progressivism of his time. Unfortunately, as discussed in this chapter, it was a message that was often obscured and overshadowed in his writing and theorizing.

EDUCATION AND TRAINING

Born in 1880, Arnold was educated in Alma through high school. In his graduating class of six, he was charged with presenting a discussion of electricity. Characteristically inventive and independent, he designed and built a large electromagnet, connected it to a power source, turned it on, and lifted an iron into the air—suspending himself from its handle (Gesell, 1952; Program for Commencement, 1896).

To prepare for a career in education, Arnold enrolled in a nearby teachers’ college, Stevens Point Normal School. There he combined his studies with captaining the second-string football team and editing the campus newspaper. Foreshadowing his success as a dispenser of advice based on rhetoric as much as on science, Gesell became a champion debater and speaker. In his second year he gave an oration on John Brown, the antislavery martyr. In it, one hears the voice of Gesell’s father, rooting for the underdog and admiring Brown for battling the forces of oppression. According to Arnold, Brown’s “deeds were neither actuated by revenge or ambition, nor tainted by vain or selfish desires, but prompted purely by a benevolent love for his oppressed fellow creatures to whose cries he opened his heart” (Gesell, 1898, p. 3).

The following year he won debate contests—first at home, next among all Wisconsin Normal Schools, and finally with winners from five Midwest states (Our Oratory, 1899). His oration, “The Spirit of Truth,” expressed his optimism and belief in social evolution. “Although the past has been dark with despair,” he noted, “the brighter era is fast coming, when man will develop, not by physical struggle, but by appeals to reason and to justice; not by catastrophe but by peaceful evolution” (Gesell, 1899, p. 77).

Two years of normal school courses qualified him to teach high school, which he did in the town of Stevens Point, Wisconsin, for 2 years. Next he enrolled at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, where he studied history with Frederick Jackson Turner and took courses in education and psychology. His senior thesis was historical, showing how colleges and universities developed in Wisconsin and Ohio—foreshadowing his career advocating school restructuring. At Madison he continued to excel as an orator and was elected president of the Athenaean Debating Society. Selected to deliver a commencement oration to a crowd of 2000, he spoke on the problem of child labor and its handling by British reformers.

At Wisconsin, the psychologist with the greatest influence on Gesell is someone ignored by biographers: Michael Vincent O’Shea, professor of education who taught Gesell while writing a text with the wonderfully progressivist title, Education as Adjustment (O’Shea, 1903). In O’Shea’s classes, students were given the scientific evidence that supported the culturally popular ideas of progressive evolution and psychological recapitulationism.

Figure 1.2 Arnold Gesell Family Burlesque (Arnold Gesell with sword). Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society [WHi 4597]. With permission.

In a course titled “Mental Development,” Gesell was taught Herbert Spencer’s (1862/1904) idea that both man and society were evolving upward. Although this was a distortion of Darwinian theory, it resonated with Gesell, who believed that socialism would arrive only after the birth of new generations of altruistic, groupminded individuals. At that time, the social order would no longer be based on selfishness. Greed would be replaced by the motives of cooperation and mutual aid.

Gesell also learned from O’Shea (1901) that childhood recapitulates the history of the human race. As he explained in an article assigned to students, “the child’s body must … retrace the steps which have been taken in the creation of the human body throughout racial history; and we are coming to see that this is the method by which the Creator works in developing not only the corporeal part of man’s nature but the mental as well” (O’Shea, 1901, p. 90). G. Stanley Hall, with whom Gesell did graduate work, was also a strong and influential propounder of this view.

Based upon this principle, Gesell’s lifelong calling became observing, protecting, and guiding the child through the environment. As O’Shea explained, the job of the educator and psychologist is “helping [the child] along, more rapidly, aiding it to overcome obstacles along the way and preventing it from arrest of growth somewhere while en route” (O’Shea, 1901, p. 90). Upon such help depended the progress of the human race.

Gesell and G. Stanley Hall

Upon graduation, Gesell served as principal of Chippewa Falls High School for a year. He then won a fellowship to pursue a doctorate in education at Clark University, studying with its president, G. Stanley Hall. As Gesell had learned from Professor O’Shea, Hall and his child study movement shared his own evolutionary view of human traits and emotions. Evolutionary theory provided the framework for Hall’s thinking about development. In the late nineteenth century, the study of development was closely tied to evolutionary theory. (For a historical survey of the relationship between the study of embryological development and evolutionary theory, see Laubichler & Maienschein, 2007, especially Part I.) Embryologists studying biological development had documented the close resemblances among embryos of diverse species, relationships that provided key support for evolutionary theory. In an 1860 letter written to the American biologist Asa Grey, Darwin (1896, p. 131) wrote that embryological evidence provided “by far the strongest single class of facts in favor of” his theory. The growing popularity of evolutionary theory also coincided and overlapped with a general growth of interest in childhood development beginning in Europe during the last half of the nineteenth century.

As noted earlier, Hall was also a strong believer in recapitulationism. To prove that the developmental sequences through which the child and adolescent pass mirror the stages through which the human species and human civilization had passed, Hall’s students used historical and observational data to show that lower instincts such as selfishness, fear of fire, and fear of water were replaced by higher ones as humans grew and societies became more advanced. At the highest level of development, one found a social order based on cooperation and mutual aid—similar to the utopias of American socialists, writings of the Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin, and the teaching of several religious orders.

The idea of recapitulation itself fell out of favor after 1910 (e.g., Davidson, 1914; Gould, 1977; Rasmussen, 1991). In the post-1900 world of genetics and experimental embryology, there was little room for the idea that individual heredity and development were directly driven by the evolutionary history of the species. Gesell acknowledged and accepted these criticisms. In a tribute to his former teacher, Gesell (1925b, pp. 126–127) acknowledged that Hall “… exaggerated the doctrine of recapitulation.” Gesell also went out of his way to deny explicitly the parallelism between the growth of culture and the growth of the individual espoused by Hall, stating that “such pretty parallelisms can nowhere be found except in the pages of a book” (Gesell & Ilg, 1943, p. 65).

Despite this difference, Gesell may be viewed as the inheritor of Hall’s mantle. Hall had introduced the child study movement to the United States in the early 1880s, and it remained influential for the next quarter century (Siegel & White, 1982). The aim of this movement was to place knowledge about child development on a firm scientific basis and to use this knowledge to improve education and the welfare of children. Hall argued for the development of a scientific pedagogy built around child study and was a strong advocate for research in child development and education. Although not really a coherent movement, those associated with it were united in their conviction that empirical research provides a sound basis for achieving practical goals. The methods Hall and others used were not primarily based on experimentation but more on naturalistic methods including questionnaires, observations, journals, parental diaries, autobiographical accounts, physical measures, and other such data (Hulbert, 2003; Siegel & White, 1982; Smuts, 2008). Although he departed from Hall’s recapitulation-based hereditarianism, Gesell continued to situate his developmental perspective in the context of evolutionary theory. Gesell’s reliance on systematic observation, and his attempts to link empirical findings on child development to public policy also connect his work to Hall’s.

In the spirit of Hall, Gesell wrote a dissertation on jealousy in animals and humans, viewed from a Darwinian perspective. In it, he offered a pedagogy of control for parents whose children showed an excess of the jealous instinct: “Develop in your children a robust spirit of self-worth…. Let them have a hobby … [as] a haven of consolation, when buffeted by rivalry … [so that they may] say after reflection, ‘I am glad to be myself’” (Gesell, 1906, p. 487). This anticipated the mental hygiene movement, with its emphasis on a properly engineered environment for children.

Postdoctoral Explorations

In fall 1906, Gesell accepted a postdoctoral job that would seem odd today. He became a teacher at a boy’s camp near Holderness, New Hampshire. Camp Asquam was a famous summer camp created by Winthrop Talbot, MD, in the 1880s. There, the sons of wealthy families were given a regimen of fresh air, sports, and outdoor culture. To Talbot, the benefits of this regimen could be seen and measured: in lung capacity, strength, and other developmental markers (Maynard, 1999). Hired to teach elementary school, Gesell joined the staff during an ill-fated attempt to run the camp year-round. Although he loved the outdoors, Gesell disparaged his boss’s grandiose plans and disliked working there; he resigned in early 1907. Next, he moved to New York City and taught school at night from February to July 1907. Significantly, he lived at the East Side Settlement House, which provided health and social services to the urban poor (Harris, 1999).

What stunned Gesell in New York were the dreary, overcrowded slums. As he later explained to an audience of teachers in training...