![]()

Chapter 1

The World of Cause and Effect

The human mind is a wonderful analogue processor. It is the most sophisticated learning processor that we know. And it learns by telling stories for itself, stories of how things are, how they came to be, what is really happening, what will happen next, and why – in short, by thinking causally, filtering out the causally relevant from the causally irrelevant. Parents will know both the joy and the frustration of that period of their child’s life when he or she endlessly asks ‘why?’.

At the heart of learning and development lies causation: as Hume remarks in his work An Inquiry Concerning Human Understanding: ‘on this are founded all our reasonings concerning matter of fact or existence’ (Hume 1955: 87). Whether or not the world itself develops and emerges through cause and effect is largely immaterial; in order to avoid circularity, this book assumes that we think and we learn in part through cause and effect. Causation is both an ontological and an epistemological matter. This is unremarkable. However, how this happens is truly marvellous, for, as this book will argue, it involves a sophisticated process of evaluation and filtering, weighing up competing causal influences and judging exactly what each shows or promises. Whether we simply impose our way of thinking – in terms of cause and effect – on unrelated objects and events in order to understand them for ourselves, regardless of the fact that such cause and effect may or may not exist ‘out there’ in the objective world – i.e. that cause and effect is a theoretical construct used heuristically for humans to understand their world – is debatable. Pace Wittgenstein, the limits of our ways of thinking may define the limits of our world. The world may be disordered, unrelated and, in terms of cause and effect, insubstantial, but it’s nearly all we have; it’s all we can do in order to understand it.

Are we to believe Russell (1913: 1), who wrote that ‘the law of causality, I believe, like much that passes muster among philosophers, is a relic of a bygone age, surviving, like the monarchy, only because it is erroneously supposed to do no harm’, or Pearson (1892), who considered causation to be a mere ‘fetish’ that should be overtaken by measures of correlation, or Pinker (2007: 209), who reports some philosophers as saying that causation is as shoddy as the material used in Boston tunnels and should be kissed goodbye, or Gorard (2001), who writes that ‘our notion of cause is little more than a superstition’? I think not. Maybe causation has little mileage for philosophers, but for social scientists it is a fundamental way of understanding our world, and we have to engage it. Indeed Pinker (2007: 219–20) shows how causation is deeply entrenched in our everyday language, in such phrases as causing, preventing, moving in spite of a hindrance, and keeping still despite being pushed.

There are several reasons why understanding and using causation are important (e.g. Lewis 1993; Salmon 1998: 3–10). For example, causation:

- helps us to explain events;

- helps us to get to the heart of a situation;

- helps us to understand why and how things happen;

- helps us to control our lives;

- helps us to manipulate our environment;

- helps us to predict events and outcomes;

- helps us to evaluate proposals and policies;

- helps us to establish ‘what works’;

- helps us to plan for improvements;

- can inform policy making;

- helps us to build knowledge cumulatively over time;

- helps us to control events to some extent;

- helps us to attribute responsibility and liability;

- is the way we think.

Understanding and using causation may not be straightforward. Indeed Glymour (1997: 202) argues that there is no settled definition of causation, but that it includes ‘something subjunctive’. Causation is a multi-dimensional and contested phenomenon. Humeans would argue that temporality is a marker of causation: one event has to precede or proceed from another in time for causation to obtain. Hume provides a double definition of causation (see his work A Treatise of Human Nature; Hume 2000: 1.3.14: 35):1

An object precedent and contiguous to another, and where all the objects resembling the former are plac’d in a like relation of priority and contiguity to those objects, that resemble the latter.

An object precedent and contiguous to another, and so united with it in the imagination, that the idea of the one determines the mind to form the idea of the other, and the impression of the one to form a more lively idea of the other.

He adds to this in his Inquiry:

An object followed by another, and where all the objects similar to the first are followed by objects similar to the second. Or, in other words, where, if the first object had not been, the second had never existed.

(Hume 1955: 87)

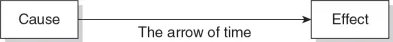

The Humean model of priority and contiguity is represented in Figure 1.1. Note that the boxes of cause and effect are joined (the ‘contiguity’ requirement) and touch each other in time; there is no gap between the boxes and the arrow. Further, the cause only ever precedes the effect (the ‘priority’ requirement).

These are starting points only – indeed, they conceal more that they reveal – and this chapter will open up the definitions to greater scrutiny. Though Hume is concerned with regularities, other views also have to do with inferences and probabilities, and this opens the door to a range of issues in considering causation.

Figure 1.1 Priority and contiguity in cause and effect

A fundamental tenet from Hume’s disarmingly simple yet profound analysis is that causation cannot be deduced by logic nor, indeed, can it be directly observed in experience (see also Fisher 1951; Holland 2004). Rather, it can only be inferred from the cumulative and repeated experience of one event following another (his ‘constant conjunction’ principle, in which the individual learns that if one event is followed by another repeatedly then it can be inferred that there is a probability that the two may be connected). This is questioned by Ducasse (1993), who argues that recurrence is not a necessary requirement of causation, that it is irrelevant whether a cause-and-effect event happens more than once, and that it only becomes relevant if one wishes to establish a causal law (Hume’s ‘regularity of succession’). Indeed Holland (1986: 950) suggests that Hume’s analysis misses the effect that other contiguous causes may have on an effect.

Our knowledge of causation is inductive and the uncertainty and unpredictability of induction inhere in it. As a consequence, knowledge of causation is provisional, conjectural and refutable. It is learned from our memory – individual or collective – as well as perhaps being deduced from logic or observation (see also Salmon 1998: 15). Indeed, so strong is the inferential nature of causation that we can, at best, think in terms of probabilistic causation rather than laws of causation. This is a major issue that underpins much of this book.

We have to step back and ask ‘What actually is a cause?’ and ‘What actually is an effect?’: an event, a single action, a process, a linkage of events, a reason, a motive? One feature of causation is its attempt to link two independent, in principle unrelated events. ‘Minimal independence’ (Sosa and Tooley 1993: 7) is a fundamental requisite of causation, or, as Hume remarks, every object has to be considered ‘in itself’, without reference to the other, and ‘all events seem entirely loose and separate. One event follows another, but we never can observe any tie between them. They seem conjoined, but never connected’ (Hume 1995: 85). Does X cause Y, when X and Y are independent entities? Does small class teaching improve student performance? Does extra homework improve student motivation? The relationship is contingent, not analytic, i.e. the former, in itself, does not entail the latter, and vice versa; they are, in origin, unrelated. Indeed, in rehearsing the argument that the cause must be logically distinct from its effect, Davidson (2001: 13) argues that, if this is true, then it is to question whether reasons can actually be causes, since the reason for an action is not logically distinct from that action (see also Von Wright 1993).

One of the significant challenges to educationists and policy makers is to see ‘what works’. Unfortunately it is a commonly heard complaint that many educational policies are introduced by political will rather than on the basis of evidence of whether they will actually bring about improvements. The move to evidence-based education has to be clear what constitutes evidence and what that evidence is actually telling us (Eisenhart 2005). In the world of medicine, a new drug might take ten years to develop, to undergo clinical trials, to meet the standards required by the appropriate authorities, and even then only between 1:2,000 and 1:10,000 drugs that have been tested are actually approved for human use. Now look at the world of education: policies and initiatives are introduced on the most slender of evidence, and a signal feature of many educational initiatives and interventions is their lack of a rigorous evidence base. There is an urgent need to understand causation in order to understand what works, for whom and under what conditions; what interventions are required; and what processes occur and with what effects. Understanding causation is vital here.

There have been several recent moves to ensure that educational policy making is informed by evidence rather than political will. For example, the Social, Psychological, Educational and Criminological Controlled Trials Register (SPECTR) has been established, with over 10,000 references (Milwain 1998; Milwain et al. 1999; Davies 1999; Evans et al. 2000), evidence is appearing in the literature (e.g. Davies 1999; Oakley 2000, Davies et al. 2000; Evans et al. 2000; Levačić and Glatter 2000), and an Evidence-Based Education Network has been established in the UK (http://www.cem.dur.ac.uk). The University of London’s Institute of Education has established its ‘EPPI-centre’: the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/EPPIWeb/home.aspx), and it has already published very many research syntheses (e.g. Harlen 2004a; 2004b). The Campbell Collaboration (http://campbellcollaboration.org) and the What Works Clearinghouse (http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/) produce an evidence base for decision making. There is a groundswell of opinion to suggest the need for evidence to inform policy making (Davis 1995; Cohen et al. 2000: 394; Levačić and Glatter 2000; Ayres 2008). We should know whether something works, and why, before we put it into policy and practice.

There is a need to bring together the worlds of research, practice and theory. Goldthorpe (2007a: 8) berates social scientists for their inability to have developed laws and to have linked research with the development of cumulative theory, as has been done in the hard sciences. This book seeks to address this matter in part. It introduces and opens up an understanding of causation. It deliberately avoids the formulaic presentations that one reads in philosophical works and works on logic. That is not to demean these; on the contrary, they are essential in clarifying and applying concepts of causation. However, it places these into words, so that the novice reader can grasp their significance for the approach adopted here.

Causation – cause and effect – is no simple matter. If only it were, but it is not! This book indicates why causation is far from being as straightforward as policy makers might have us believe. It is complex, convoluted, multi-faceted and often opaque. What starts out as being a simple exercise – finding the effects of causes and finding the causes of effects – is often the optimism of ignorance. One can soon become stuck in a quagmire of uncertainty, multiplicity of considerations, and unsureness of the relations between causes and effects. The intention of this book is to indicate what some of these issues might be and how educational researchers, theorists and practitioners can address them. The book seeks to be practical, as much educational research is a practical matter. In this enterprise one important point is to understand the nature of causation; another is to examine difficulties in reaching certainty about causation; another is to ensure that all the relevant causal factors are introduced into an explanation of causation; and yet another is to provide concrete advice to researchers to enable them to research causation and cause and effect, and to utilize their findings to inform decision making.

A final introductory note: readers will notice that the term ‘causation’ has been used, rather than, for example, ‘causality’. This is deliberate; whilst both terms concern the relation of cause and effect, additionally ‘causation’ is an action term, denoting the act of causing or producing an effect. It expresses intention (Salmon 1998: 7). This is close to one express purpose of this book, which is to enable researchers to act in understanding and researching cause and effect.

Implications for Researchers:

- Consider whether the research is seeking to establish causation, and, if so, why.

- Consider what evidence is required to demonstrate causation.

- Consider whether repeating the research is necessary in order to establish causation.

- Recognize that causation is never 100 per cent certain; it is conditional.

- Decide what constitutes a cause and what constitutes the effect.

- Decide what constitutes evidence of the cause and evidence of the effect.

- Decide the kind of research and the methodology of research that is necessary if causation is to be investigated.

- Decide whether you are investigating the cause of an effect, the effect of a cause, or both.

- Causation in the human sciences may be probabilistic rather than deterministic.

![]()

Chapter 2

Tools for Understanding Causation

This chapter traces in some key concepts in approaching and understanding causation, and, in doing so, indicates some of the historical antecedents of the discussion. As the chapter unfolds, it indicates an ever-widening scope of the concept of causation, beggaring naïve attempts to oversimplify it. At each stage of the discussion implications are drawn for educational researchers.

There are d...