![]()

Chapter 1

Group Care Practice with Children Revisited

Leon C. Fulcher

Frank Ainsworth

SUMMARY. Using a comparative analysis group care for children and young people is examined as an occupational focus, as a field of study and as a domain of practice in programs that range from residential institutions to group homes and kin group foster care. Structural issues that shape the interplay between organizational dynamics and interpersonal processes are considered, as well as the ways in which group care services have evolved historically and continue to feature prominently in the health, education, justice and welfare systems of both developed and developing countries.

[Article copies available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service: 1-800-HAWORTH. E-mail address: <[email protected]> Website: <http://www.HaworthPress.com> © 2005 by The Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved.] KEYWORDS. Group care, residential care, residential treatment, group homes, youth work, youthwork, group work, at-risk youth, deinstitutionalisation, mainstreaming, least restrictive environment

After receiving many requests for a new edition of Group Care for Children (Ainsworth & Fulcher, 1981) and Group Care Practice with Children (Fulcher & Ainsworth, 1985), originally published in the United Kingdom, we decided to develop a single volume drawing on selected materials from these publications. Interestingly, over the past two decades the term “group care” has acquired a wider currency as evidenced by the number of subsequent publications that now use this terminology (Ainsworth, 1997; Anglin, 2003; Carman & Small, 1989; Davison, 1995; Epstein & Zimmerman, 2003; Gitelson & Emery, 1989; Levy, 1993; Powell, 2000; Rossenfeld & Wasserman, 1990; Zimmerman, Epstein, Leichtman, & Leichtman, 2003).

In this new volume the aim has been to once again draw together materials from both sides of the Atlantic and draw on knowledge from Australia and New Zealand–and South Pacific island nations influenced by trans-Tasman policy and practice perspectives–as well as Indonesia and Malaysia. These perspectives have become familiar to the authors since publication of the original volumes through experiences that have confirmed the continuing relevance of the concepts and issues identified in the 1980s. Added to this are views about various developments that have influenced the field since that time. Former contributors to the original volumes were invited to reflect on developments that have taken place in their substantive fields of enquiry since publication of the original materials and to re-visit those themes still considered central to “best practice” in the field of group care. In so doing our commitment to comparative international and historical methods of enquiry has been maintained while addressing the continuing development of services for children and young people.

GROUP CARE AS A FIELD OF STUDY

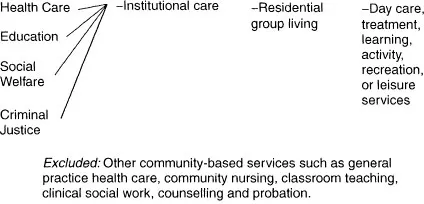

By way of introduction to this new volume, the notion of group care is again set out and examined as a unique field of study. A number of devices are used in order to achieve this. First, it is noted how group care facilities are found in each of society’s major resource systems: health care, education, social welfare, and criminal justice. This is achieved by highlighting the presence of comparable large institutions in each of these systems: mental hospitals in health care, boarding schools in education, orphanages and community homes in social welfare, and prisons or reformatories in criminal justice. The extent to which institutions such as these reflect the historical development of the field of group care is also acknowledged, as is the manner in which client populations in each type of institution may overlap. The presence of different types of institution in each of society’s major resource systems is highlighted in Table 1.

Attention is also directed towards the emergence in each of the four resource systems of a range of smaller group living situations; these are often developed in response to criticisms of the debilitating nature of life in large institutions. These smaller group living situations are identified as residential nurseries, family group homes, peer group residences, hostels, refuges, shelters, or semi-independent group living units. Finally, it is noted how there has been the apparently simultaneous growth across all four resource systems of various types of day service provisions, each with a designated centre of activity where services are delivered to individuals through the medium of group care, as illustrated in Table 2.

Thus it is possible to delineate a composite profile of the group care field as it incorporates institutional care, residential group living, and day care services operating across all four of society’s major resource systems, as shown in Figure 1.

What is excluded are community-based services such as general practice health care, community nursing, classroom teaching, clinical social work, counselling, and probation. As a result of the foregoing analysis, it is possible to delineate the field of group care.

TABLE 1. Large Institutions Across the Major Resource Systems

|

| Health Care | Education | Social Welfare | Criminal Justice |

|

| Asylums Mental Hospitals Hospitals for the Mentally Retarded General Hospitals | Day & Boarding Schools for Normal, Maladjusted, & Emotionally Disturbed Children Hotels Residential Colleges Halls of Residence | Orphanages Prisons Lodging Houses Reformatories Emergency Care Centres Community Homes | Prisons Reformatories Remand/Detention Centres Training Schools |

(Ainsworth & Fulcher, 1981, p. 4)

Group care incorporates those areas of service such as institutional care, residential group living (including–but not necessarily requiring–twenty-four hour, seven day-per-week care), and other community-based day services covering lesser time periods that supply a range of developmentally enhancing services for groups of consumers. The location of a service in the group care field results from identifying how each type of service places emphasis on shared living and learning arrangements in a specified centre of activity. (Ainsworth & Fulcher, 1981, p. 8)

TABLE 2. Range of Day Services Across the Major Resource Systems

|

| Health Care | Education | Social Welfare | Criminal Justice |

|

| Day Hospitals Day Clinics Health Centres Day Nurseries | Youth & Community Centres Recreation & Leisure Centres Day Nurseries Day Schools Intermediate Treatment Units Alternative Schools | Day Care Child Care Centres Play Groups Activity Programs Intermediate Treatment Units | Community Service Centres Day & Project Centres Intermediate Treatment Units |

(Ainsworth & Fucher, 1981, p. 8)

FIGURE 1. The Field of Group Care Across the Major Resource Systems

(Ainsworth & Fucher, 1981, p. 8)

In making such a statement, efforts were made to resist a superficial dichotomy that has prevailed in the human services where institutional care is located at one end of the continuum of care with day services located at the other extreme (Jones & Fowles, 1984). Such a dichotomy between institutional and community-based services is resisted since it is based primarily on a social policy perspective and fails to acknowledge the structural, organizational, and interpersonal processes that require stronger emphasis (Glaser & Strauss, 1967).

All forms of institutional care, residential group living, and day services operate with a group focus using the physical and social characteristics of a service centre to produce a shared life-space (Lewin, 1952; Redl, 1959) between those in receipt of care and those who provide it. By identifying the field of group care as it spans each of society’s four major resource systems and by drawing attention to common characteristics of programs in this field, it is possible to identify group care as a discrete area of practice that needs to take its rightful place alongside other services offering benefits to children, young people, and their families.

THE PURPOSE OF GROUP CARE FOR CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE

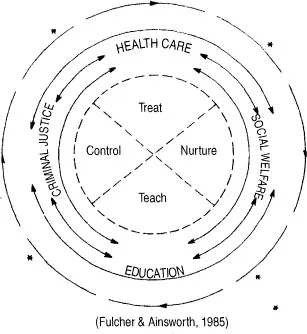

Before examining the methodological basis of group care practice with children and young people, some comment is necessary about the purposes or functions of group care identified in Group Care for Children: Concept and Issues as “supplying a range of developmentally enhancing services for children and young people” (Ainsworth & Fulcher, 1981, p. 8). Health care, education, social welfare, and criminal justice are, of course, much broader in conception than the field of group care as defined above. In fact, each system has evolved over time in response to widely held notions of personal and societal need. It is thus worth clarifying the central notion or purpose that underpins each of the systems in question. The major purpose for health care is to treat, for education to teach, for social welfare to nurture, and for the criminal justice system to control.

Inevitably, each system embraces value preferences, organisational features, and occupational characteristics that reflect its own primary purpose or tasks. As far as group care services for children and young people are concerned, this creates a dilemma irrespective of the resource system that sponsors such services. In each instance, these functions must be woven firstly and importantly around what Maier (1979; 1981) described as the “core of care” as without such expression and care experience by the individual patient, student, client, or inmate, developmental change is unlikely to occur, and treatment, learning, development, or rehabilitation goals will not be achieved.

Yet experience has shown that such a care ethos is difficult to achieve. It is frequently compromised, since most group care centres are dominated by the single–yet simplistic–purpose that underpins the sponsor of its resource system. This results in an incomplete response to the personal and behavioural needs of children and young people who are searching for developmentally enhancing services.

FIGURE 2. Resource System, Underlying Purpose, and Areas of Overlap in Group Care

Figure 2 enables one to explore some of these issues more clearly. First, it is possible to examine a largely static portrayal of the ways in which each of society’s resource systems reflects a single purpose and how group care centres, sponsored by that system, are likely to emphasize a specific purpose or primary task. By including illustrations of group care services that combine more than one purpose or that seek to transcend the boundaries between systems, the intention has been to offer a more dynamic or interactive perspective, for example, residential treatment centres for emotionally disturbed children that provide both education and psychiatric services (i.e., social welfare, education, and health care), a children’s hospital that provides schooling for long-stay patients (i.e., health care and education), or a detention centre for young offenders that offers in-house education and psychiatric services (i.e., criminal justice, education, and health care). It is worth noting, however, that centres seeking to transcend boundaries–and thereby address broader conceptions of children’s developmental needs–are all too often faced with controversy.

Public debate frequently surrounds the operation of what might be called hybrid programs. This is the case even when a multiple focus or a blending of functions may be in the best interests of young people and their developmental progress. Having made this point, it is thus possible to proceed to a consideration of the methods or skills basis of group care practice.

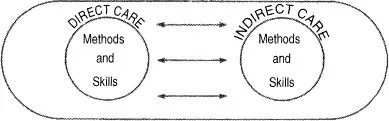

GROUP CARE METHODS AND SKILLS

In Chapter 9 of Group Care for Children, about the training of group care personnel, Ainsworth (1981) divided practice into direct and indirect care as a way of starting to map out group care practice methods and skills. The intention of Figure 3 below is to highlight the ways in which both areas of skills have to interact in a dynamic yet ordered manner if responsive care is to be guaranteed.

FIGURE 3. Group Care Methods and Skills

Direct care involves working face-to-face with children and young people, while indirect care involves work carried out for and on behalf of children but not necessarily with them directly. Such a distinction helps to clarify the tasks carried out by different practitioners and the variety of activities that take place in any group care program. Of course, it is important to guard against the static picture that Figure 3 can convey, for there is no wish to reduce complex relationsh...