![]()

1 INTRODUCTION

The change from horse-drawn to motor traffic was a revolution, and nothing less than a corresponding revolution in roads and road user will suffice to put things right.

Alker Tripp, Road Traffic and Its Control1

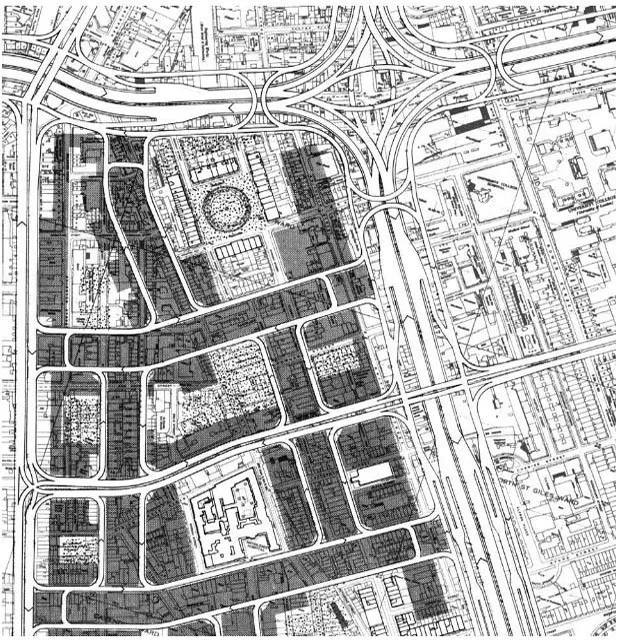

In 1963, the UK Buchanan Report on Traffic in Towns laid out a vision of urban design for the motor age. This envisioned cities of multi-lane motorways and multi-storey car parks, with tower blocks and pedestrian decks set above labyrinthine systems of distributor roads and subterranean service bays. Central London was shown transformed into a vast megastructure complex sprawling across Fitzrovia and Bloomsbury, vividly demonstrating the ‘radically new urban form’ demanded by the motor vehicle.2

The image opposite was merely intended as an illustration of the Report's implications – demonstrating what could be required if society chose to take the accommodation of motor vehicles to its logical conclusion. Had this choice been taken up, the result would have been a dramatic transformation of towns and cities – and not least of the portion of inner London illustrated.

A bustling commercial street, Tottenham Court Road, would be transformed into a multi-lane motorway, terraced and flanked on either side by parallel collector-distributor roads, forming a traffic canyon some 100 m wide, accommodating a dozen lanes of traffic. Its four-level intersection with Euston Road would occupy an area that could accommodate a hospital or university ().3

Such surgery would scarcely be contemplated today. Already, by the early 1960s, the wisdom of highways-driven city redevelopment was being questioned by radical urban writers such as Jane Jacobs, who saw streets as the lifeblood of cities rather than mere traffic channels; and subsequently by Christopher Alexander, who saw streets as multi-functional urban ‘patterns’.4

1.1 • Inner London transformed. In this illustration from Traffic in Towns, the north-south commercial street Tottenham Court Road is replaced by a multi-lane motorway, severing the Fitzrovia district (west) from Bloomsbury (east).

But, in the vision presented in Traffic in Towns, the role of Tottenham Court Road as an urban ‘seam’ between Fitzrovia to the west and Blooms- bury to the east would disappear as those districts became separated, insular precincts. Shops would be marooned on the pedestrian deck, away from passing trade. Buses would be abandoned in the limbo of the district distributor level. The familiar urban ‘patterns’ of the grocery store by the bus stop, and the pub on the street corner, would be lost. There would be no pub on the corner, since no building would interfere with the requisite junction visibility requirements. There would be no crossroads, since these would be banned on traffic flow and safety principles. Indeed, there would be no ‘streets’: just a series of pedestrian decks and flyovers.

The vision was more than a fleeting urban hallucination from the 1960s. It expressed principles that were to become the prevailing norm for urban road layout, not only in Britain, but around the world. It was no less than a snapshot of an unfolding urban revolution.5

REVOLUTION

What was this urban revolution all about? At heart, the traditional pattern of urban structure constituted by streets was swept away by a brave new system of vehicular highways separate from buildings and public spaces. Richard Llewelyn-Davies called this the ‘revolutionary, even cataclysmic, impact of modern transport planning on the form of towns’.6 In the second half of the twentieth century, as the car and the modern highway took a grip on urban design, city form underwent perhaps its most dramatic transformation in thousands of years.7

The cataclysm of Modernism was not just about comprehensive redevelopment and the introduction of a new kind of infrastructure – that had happened before, when the railways entered the Victorian city. What modern road planning did was to alter the fundamental relationship between routes and buildings. It effectively turned cities inside out and back to front.

The cata clysm of Modernism

Over the course of history, all sorts of urban activities have taken place on the main streets: they were not just for through passage, but for meeting, trading, hawking, busking, bear-baiting, public speaking and pillorying. If anything, there seemed to be a natural relationship between the busiest, most vital streets and the most significant urban places (Figure1.2).

1.2 • Dunbar in 1830. The high street is the widest street and the most significant urban space in the village. The main street has wells and a weigh-house – this hints at the variety of urban activities present.

Modernism not only broke this relationship between movement and urban place: it reversed it. It proposed an inverse relationship between movement and urban place. The movement would now be the movement of fast motor traffic; the urban places would become tranquil precincts.

In the UK, Alker Tripp had already promoted the idea of turning existing arterial streets into segregated highways for motor vehicles, like railways, barred to public access. The main streets would have their buildings turned back to front, and side roads disconnected. As Tripp calmly put it: ‘Roads- ends need not be closed up with bricks and mortar; a row of posts will suffice for the present.’8 Colin Buchanan later commented:

It is when one considers carefully the full implications of Alker Tripp's theory – the searing of the town with a railway-like grid of roads and the literal turning of the place inside out – that the first qualms arise and one asks whether, if this is the price to be paid for the motor car, it is really worth having.9

Despite these qualms, Buchanan made the founding principle of Traffic in Towns the distinction between roads for traffic and those providing access to buildings. This directly echoed the approach of Tripp two decades earlier, who asserted that these two functions were ‘mutually antagonistic’, and must be separated in two kinds of urban road.10

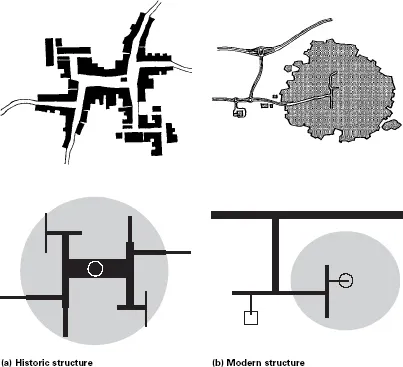

This, in a sense, turned the road system itself upside down. Formerly major streets became backwater access roads or pedestrian precincts. The most important traffic routes were no longer streets. The relationship between main routes and central places was reversed (Figure1.3).

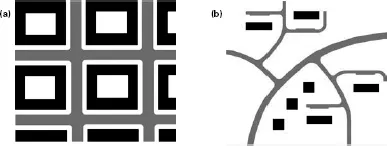

1.3 • Caricature of historic and modern settlement structures. (a) The market square is centre stage, and the intensity of circulation dissipates outward from this core. The routes out of town are of a relatively low standard. (b) The main flows and highest standard routes are on the national network outside the town. The relationship between notional centre and main routes is reversed.

The historic pattern of accessibility focused on the centres of settlements became replaced by accessibility distributed around the urban periphery. Whole settlements became, in the words of the writer Alex Marshall, ‘appendages off a freeway ramp’.11 At the scale of urban streets and blocks, modern road systems also turned pockets of the urban fabric ‘inside out’, inverting streetspace as the focus of public space.

Tripp prefaced his comments on how streets should be redesigned with the telling phrase ‘from the traffic point of view’. With hindsight, this point of view seems to have been built into much of urban planning policy in the second half of the twentieth century, often appearing to have priority above all others. And as a central plank of Modernist policy it was adopted enthusiastically by engineers, architects and planners alike. The circulation system has always formed the ‘backbone’ of settlements; but traditionally it was streets that performed this spinal role. In contrast, Modernism filleted the city – stripped the spine and ribs out from the urban flesh, and set up the road network as a separate system.

The dissembly of the street

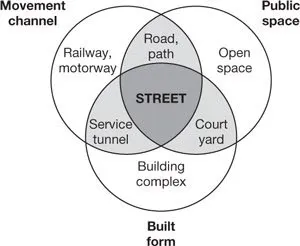

The urban street had traditionally united three physical roles: that of circulation route, that of public space, and that of built frontage. These three elements may be loosely equated with the linear concern of the transport engineer (the street as a one-dimensional ‘link’ in the traffic network), the planar concern of the planner (streetspace as land use) and the three- dimensional concern of the architect or urban designer (Figure1.4).

1.4 • Elements of the street.

However, the revolutionary rhetoric of Modernism passed a death sentence on the street. Modernism set up a new urban model that liberated the forms of roads and buildings from each other. Rather than being locked together in street grids, the Modernist model allowed roads to follow their own fluid linear geometry, while buildings could be expressed as sculpted three-dimensional forms set in flowing space (Figure1.5).12 Each

1.5 • Traditional versus modern layouts. (a) Fit of roads and buildings. (b) Roads and buildings follow their own dedicated forms. form could follow its own dedicated function, resulting in a divergence of forms and quite separate geometries for buildings and roads. The street, in official vocabulary, ceased to exist.13

The schism of Modernism

This effectively amounted to a schism in urban d...