eBook - ePub

Around the Tuscan Table

Food, Family, and Gender in Twentieth Century Florence

This is a test

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In this delicious book, noted food scholar Carole M. Counihan presents a compelling and artfully told narrative about family and food in late 20th-century Florence. Based on solid research, Counihan examines how family, and especially gender have changed in Florence since the end of World War II to the present, giving us a portrait of the changing nature of modern life as exemplified through food and foodways.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Around the Tuscan Table by Carole M. Counihan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences sociales & Anthropologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Food as Voice in Twentieth-Century Florence

Introduction

Non è nemmeno che s’abbia più desideri, fifty-year-old Valeria commented in 1984: It’s not that we have any more unfulfilled desires. We eat whatever we want every day. If we have any desires it’s to eat the old cheap foods like minestra di pane (bread and bean soup), or cornmeal gnocchi (dumplings). We eat meat all the time. Instead, in the old days, we really craved meat and we ate it enthusiastically. Now when we go out, what do we eat? More or less the same things that we always eat at home. When Sunday comes, it is a day like every other…. You no longer have any yearning for anything. Non hai mica più voglia di niente.

Valeria touched on a major accomplishment of Italian society in the second half of the twentieth century, which was to overcome centuries of food scarcity and to provide dietary abundance for most people. Yet she also touched on the bittersweet side of that abundance, which was the loss of longing. As she and other Florentines spoke about food, they revealed rich dimensions of their lives. Eating played an important role in people’s family life, sociability, celebrations, and pleasure. Everything to do with food was important and interesting. Tastes were rich and delicious, smells fragrant and pungent, hungers strong and deep. Florentines bonded and argued at meals, and renewed or ruptured relationships through giving, receiving, or refusing food. The division of labor around food revealed gender roles and relations. Cooking for some women was an expression of creativity and caring; for others it was a burdensome obligation. In pregnancy and breast-feeding, women created relationships with their children. In eating, Florentines connected to their environment, ensured their survival, and affirmed a variegated cuisine and culture. Their foodways expressed values and habits central to their lives. This book uses food as a lens to describe Florentines’ changing family, gender relations, and ideology throughout the massive transformations of the twentieth century.

Food-Centered Life Histories as Voice

For many people, food is a powerful voice,1 especially for women, who are often heavily involved with food acquisition, preparation, provisioning, and cleanup. Food-centered life histories have fit my desire to use ethnography to give voice to traditionally muted people—people not part of the political-economic or intellectual elite, especially women. I began my study in Florence on women, and conducted multiple interviews with some, but eventually also included men to have a full picture of gender. My goal is to make the food-centered life histories carry the purpose of the testimonios, which the Latina Feminist Group (2001, 2) defines as “a crucial means of bearing witness and inscribing into history those lived realities that would otherwise succumb to the alchemy of erasure.”

The food-centered life histories of the twenty-three Florentines I interviewed between 1982 and 1984 speak out against “the alchemy of erasure,” for the lives they describe are already gone due to the rapid pace of change in the second half of the twentieth century. The core of Tuscan cuisine rooted in mezzadria peasant farming persisted at the dawn of the new millennium, but there were changes in daily meal routines, diet, cuisine, and food labor that revealed significant changes in Italian culture.

In the food-centered life histories, I asked questions about experiences and memories centered on food production, preservation, preparation, consumption, and exchange. I asked about past and present diets, recipes, everyday and ritual meals, foods for healing, eating in pregnancy, breast-feeding, eating out, and processed foods. As Florentines spoke about these topics, they provided rich data on individual perceptions of food and culture in twentieth-century Italy. This book uses their interviews to contribute the largely missing voices of the consumers themselves to the burgeoning social science literature on Italian foodways conducted by historians, ethnographers, and sociologists.2 As much as possible, this book foregrounds Florentines’ descriptions of their lives, and my words provide context and structure.

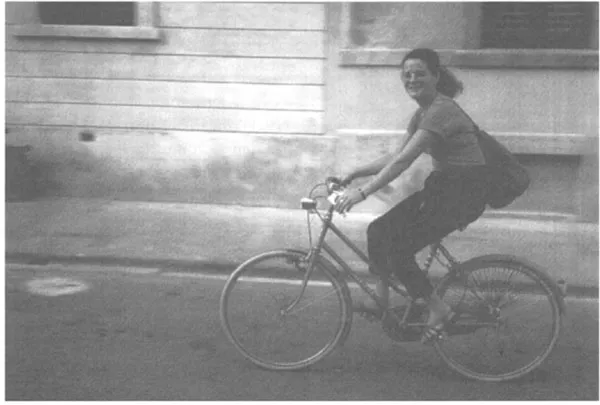

I first came to Florence as a student at Stanford-in-Italy in 1968 and returned after college graduation in 1970. I spent the next fourteen years living off and on in Italy, spending about six years total there, first holding a variety of temporary jobs and later conducting ethnographic fieldwork in Sardinia and Florence (see Figure 1.1). I had a long-term relationship with a Florentine I call Leonardo,3 and the principal data for this book come from fifty-six hours of food-centered life histories tape-recorded in Italian with Leonardo’s twenty-three living relatives in 1982–84.1 interacted with Leonardo’s relatives on many occasions between 1970 and 1984 and did participant observation of many meals. In 1984, two of my subjects recorded all their family food expenditures for one week. Eight kept weeklong daily food logs, recording what, when, and where they ate as well as their feelings before and after eating, covering a total of fifty-three days. I collected approximately two hundred recipes through observation, informants’ descriptions, and two women’s handwritten cookbooks.

Fig. 1.1 The author heading off for an interview in summer 1984

I returned to Florence in March 2003 and visited many of my previous informants, met the several new additions to their families, caught up on family history, and asked about current food habits. I did focus group interviews at two university-level classes: one in Italian at the University of Florence and one in English with third-year students at the Scuola Superiore per Interpreti e Traduttori, also in Florence.

The heart of the book consists of the edited interview transcriptions. It took me several years, but I eventually transcribed the tapes into over one thousand pages of text. I sorted my interviews into themes, selected representative passages, translated them into English, and wove them together. Creating a coherent narrative was a complex process and involved shaping the original flow of words in three main ways. The first was through translation. Interviewees spoke to me in colloquial Florentine Italian, and I have tried to stay as close to the original as possible while also providing idiomatic equivalents of untranslatable Florentine expressions.4

The second way I have shaped Florentines’ words has been through the process of editing their spoken narratives into a coherent written text. This editing has involved eliminating repetition; deleting unnecessary expressions like “I don’t know,” “You see,” and “Understand”; adding occasional words for clarity and context; and sometimes changing the order of sentences or paragraphs to construct a more logical progression of ideas. To indicate our different voices, I interweaved their words in italics with mine in Roman type.5

Finally, I shaped the many diverse interviews into a narrative about modernity, family, and gender. In the twentieth century, Florentine foodways evolved from a centuries-old, localized, sharecropping system toward a global market economy, revealing a changing cultural philosophy in beliefs and practices of consumption. My subjects described a set of gender relationships and self-definitions grounded in the extended, closed, male-headed family. They ate a “Mediterranean” diet, scantily in the first half of the twentieth century but with increasing abundance in the second half. This diet, however, was already being modified by the postmodern, ever-larger agro-food industry that continued to grow in 2003, but which Florentines and other Italians shaped by alternative food practices.

Food as Voice of Modernity

This book looks at how Florentines spoke through food about the complex changes in their lives that I consider together as “modernity.” By modernity, I mean the processes of social and economic change engendered by capitalism, technology, and informational and bureaucratic complexity that transformed Italy (and the globe) in the twentieth century. Modernity involved a transition from a localized subsistence and market economy that provided most people with barely enough to survive to a fully market, wage labor economy of conspicuous consumption, with altered social relations and meaning systems viewed here through the lens of food.6

The transition to modernity in Italy was born out of the rubble of the two World Wars and the intervening years of Fascist rule. It was jump-started by the massive U.S. aid that poured into Italy through Marshall Plan funds and private investment after World War II. It was marked by increasing abundance as the war receded and the economy rebounded. It was an abundance that the children born after the war took for granted in ways that still astounded their parents in the 1980s. We should have talked about the past more, said Baldo, born in 1930, lamenting his children’s lack of understanding of the conditions of his childhood when he had only two outfits, and if they were dirty, he stayed home, because he had nothing else to wear. His family ate watery soup and ate it willingly, because that’s all there was, and it staved off hunger. After the war, most Florentines achieved a much higher standard of living, and they gradually lost some of the traditional foods of their hungry childhoods. They lived farther from the land in urban apartment buildings or row houses, participated in an ever more fully commodified economy, and increasingly ate foods produced primarily for exchange and profit rather than for subsistence.

These changing foodways accompanied a changing Florentine value system.7 My older subjects grew up taking great pleasure in food but avoiding gluttony. Eating brought deep feelings of pleasure and consolation, but also concerns about immoderation. Medical and nutritional beliefs stressed balance in types and quantity of foods. Too much food disturbed the equilibrium between desire and satiety, and between measure and excess. When my older subjects were young before and during the Second World War, consumption was highly valued because it was scarce and precarious. Yet their children, born after the war in the context of the Italian economic miracle, grew up in a world where consumption was obligatory, taken for granted, and essential to full personhood—a transformation lamented by the older people.

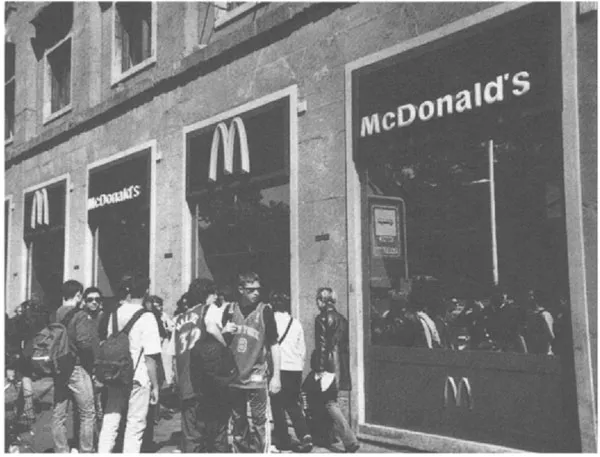

Fig. 1.2 McDonald’s in Florence, frequented heavily by young people, in March 2003

In the 1980s, children were fussy about food and strangers to the parsimony that their parents espoused, as were their children in 2003. They ate what they wanted, demanded variety, and brooked no expense in going out to eat. They ate some of the foods of the past out of nostalgia and genuine appreciation, but rejected others as distasteful. They ate and invented new foods, further from the traditional roots of Tuscan cuisine, dependent on processed ingredients, quick to make, easy to clean up, higher in meat and fats, and lower in vegetables, fiber, and legumes. In the last two decades of the twentieth century, they began to consume more junk food, and by 2003, there were four McDonald’s outlets in Florence (see Figure 1.2). Florentines ordered take-out pizza and could choose from over four hundred restaurants, of which approximately fifty-five offered foreign cuisines from ten different countries. From a value on highly pleasurable but measured consumption of quintessentially Tuscan foods emerged the commodification of food, its re flection of an ever-wider world, and a growing commitment to consumption for its own sake.

Food as Voice of Family and Gender

In talking about foodways, Florentines not only opened a window into their experiences of social change, but also revealed family and gender relations through men’s and women’s roles in production and reproduction. By production I mean the work involved in making the raw materials, products, and money that ensured survival. By reproduction I mean the labor involved in having offspring, feeding and clothing them, and socializing them to be capable members of society. Engels (1972, 71) defined the relationship between production and reproduction as “the determining factor in history” in regard to gender relations— an insight that has been pursued by several recent feminist scholars.8 Engels underscored how the privatization of the reproductive labor so universally associated with women was a key force in their subordination. He noted that in the “old communistic household” women’s work was “public” and “socially necessary,” but in the monogamous, nuclear family “household management lost its public character. It no longer concerned society. It became a private service; the wife became the head servant, excluded from all participation in social production” (Engels 1972, 137).

Throughout the twentieth century, peasant and working-class Florentine women had almost total responsibility for reproduction, and some may have felt like “the head servant.” Although women consistently participated in production, their labor was often undervalued and underpaid. Men gained status by performing socially valued production, their main role. They worked hard outside the home, but most were largely free of responsibility for reproductive labor in the home. Having primary responsibility for home and food contributed to Florentine women’s low status, as it has historically done for women the world over.9 This gender division of labor persisted throughout much of the twentieth century, and only at the turn of the millennium were there signs that young men and women were coming closer to parity in work inside and outside the home. This study hopes to contribute to feminist anthropology by using food as a conceptual lens to show how diverse arrangements of production and reproduction affected gender power in evolving twentieth-century Florence.

Chapter 2 describes the overarching structure of Florentine cuisine and its reflection of class, culture, and ideology. Chapter 3 locates the roots of Florentine foodways in history, beginning with the mezzadria peasant mode of production, which under rare optimal conditions produced a diversified, delicious, and healthy cuisine. But the peasants’ ability to have adequate food competed with landlords’ efforts to squeeze maximum surplus out of them, making scarcity a chronic threat. Women crossed the boundaries between production and reproduction because they worked in the fields, courtyard, and garden, as well as in the house. Their work was visible and recognized, but valued economically lower than the work of men who were legal heads of households. Two world wars and twenty years of fascism dealt a deathblow to the mezzadria system and its family structure, and launched the “Italian economic miracle” and transition to a fully capitalist mode of production.

Chapter 4 describes the Florentine diet and principal foods eaten by my subjects in the 1980s, and differences both from the first half of the twentieth century and from its close. Their foods still showed their roots in the peasant cuisine of the past but evinced changes due to prosperity and urban residence. These changes accelerated in the last two decades of the twentieth century, and by 2003 major changes had occurred in food, diet, and meals.

Chapters 5 and 6 describe how Florentine production, reproduction, and gender relations shifted as peasants migrated to the city and became laborers, artisans, and entrepreneurs. When families left the land, women’s chores were privatized and lost social value, yet they were still a compelling component of women’s identity and interfered with their ability to work outside the home. In the 1950s, ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, many Italian women were full-time housewives—a relative historical anomaly that the close of the millennium was reversing. In the 1980s, men accepted their privilege of irresponsibility in the home and women complied in the imbalance in...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- 1: Food as Voice in Twentieth-Century Florence

- 2: Florentine Cuisine and Culture

- 3: Historical Roots of Florentine Food, Family, and Gender

- 4: Florentine Diet and Culture

- 5: Food Production, Reproduction, and Gender

- 6: Balancing Gender Differences

- 7: Commensality, Family, and Community

- 8: Parents and Children: Feeding and Gender

- 9: Food and Gender: Toward the Future

- 10: Conclusion: Molto, Ma Buono?

- Appendix A: Life Synopses of Subjects in 1984

- Appendix B: Glossary of Italian Terms

- Appendix C: Recipe List: Recipes Collected from All Subjects

- Appendix D: Recipes

- Notes

- Bibliography