1

WHAT’S THE STORY WE WANT?

As of this writing, the twenty-first century is almost 20% behind us. And when we consider that a child born today may live to see the year 2100, “21st century learning” seems downright inadequate as the blueprint to prepare students. Isn’t it time we considered educating for the twenty-second century? This chapter will orient us to the path ahead.

Given our context is sustainability and social justice, you can just about guarantee that you’re in for a sobering account of the world’s problems: climate change, racial inequality, violence … the list, unfortunately, goes on. You’ll hear some of those troubles in the pages to come—intellectual honesty demands it—but simply asking, What’s wrong with the world? sets us up for apathy. A litany of woes can weigh us down so hard that it becomes impossible to look up and imagine a way out. That’s why I’ll start our journey with a different question: What’s the story we want for ourselves, our students, and our communities, near and far?

In workshops and courses over the past 22 years, I’ve posed this question to people of all ages and backgrounds: children, preservice educators, inservice teachers, college professors and administrators, self-identified “conservatives” and “progressives,” veterans, Catholic nuns, and other people of faith. Sometimes I use one of these variations:

What do we need for a fulfilling life?

What do we need to be happy and healthy?

What does it take to thrive as individuals and communities?

Regardless of the wording or audience, the answers have been remarkably the same. Before I reveal them, take a moment and respond yourself. Tip: Try organizing your responses by category, such as physical needs, social needs, economic needs, among others.

All done? Here are the responses I hear every (and I mean every) time. Drumroll, please.

Clean water and air;

Healthy, affordable foods appropriate to cultures and communities;

Health care;

Supportive and loving relationships: family, friends, neighbors;

Educational opportunities: schools, books, Internet, informal learning;

Economic opportunities: jobs, access to financing;

Transportation, energy, infrastructure;

Fair governance structures; and

Recreation and self-expression: hobbies, art, music, sports, etc.

This list reflects common “ingredients” essential to a fulfilling life (Ben- Shahar, 2007). While I’ve heard these responses countless times, I never tire of seeing people light up when—often for the first time—they speak about what they want, not what they fear, avoid, or lament. And when I ask a related question—What do we want for our students?—the responses again are strikingly similar: high-quality learning and opportunities for LL student A to become well-rounded people, involved citizens, and contributing members of society. The conversation expands, and we consider whether the goals apply across places, cultures, and generations. The answer has been an overwhelming yes, albeit with variations. For example, some participants raise the fact that education must adapt to the local context, while others point out that definitions of beauty are culturally determined. Absolutely. Through these discussions, participants acknowledge that, while specifics can and should vary, the desire to thrive is widely shared and (as some participants say) a “timeless” goal.

Here’s the punch line: I have yet to meet anyone who does not want strong families, healthy communities, and students who fulfill their potential. But it’s this very universality that calls out the elephant in the room: Who is responsible for the provision of healthy foods, safe housing, education, and other “ingredients” of thriving? Are they a social right, or are individuals responsible for acquiring them through their own efforts? Is it a combination of both? This eternal debate requires extended inquiry; however, I raise it now because I’ve found that no matter where people fall on the issue, they tend to agree on a basic premise: Everyone should at least have a fair shot in life. Even firm advocates of individual responsibility acknowledge that the proverbial “level playing field” is a central value of our democracy. In this way, we establish fairness and opportunity as conditions for thriving.

The vision and values I hear again and again are hardly anecdotal; indeed, they are articulated at the global level through the Earth Charter (EC), an “international declaration of fundamental values and principles for building a just, sustainable, and peaceful global society” (Earth Charter Initiative, 2016). The EC began taking shape before the 1992 Rio Earth Summit, and after a decade of global-level consensus building, the EC was launched in 2000. Underscoring the “great peril and great promise” of the future (Preamble), the EC is built upon four pillars: Respect and Care for the Community of Life; Ecological Integrity; Social and Economic Justice; and Democracy, Nonviolence and Peace. The EC Initiative continues today through education and community-level actions.

Before we get all Pollyanna, let’s be clear that we can’t rest on a vision, bring it in for a hug, and call it a day. Far too many individuals, schools, and communities are not thriving, and we must determine how to change this and define our ethical obligations as educators. There’s no feel-good consensus for that. But imagining a happier story better positions us for success than simply wringing our hands. Articulating a vision is inherently motivating because it illuminates a destination and holds up the goals worth striving for. It also prompts us to celebrate progress we’re already making, whether it’s better achievement or a stronger local economy. This mindset enables us to say, “Yes, there are problems, but there are also solutions—and some are happening now.”

Is this idealistic? Yes (and I’ve shared the pitfalls of that). But we are failing our students if our curriculum sends the message that the problems are too big and it’s pointless to try. We don’t want the takeaway to be, “Forget about thriving, kids. The best we can hope for is to simply survive.” That’s not the stuff of schoolwide themes.

With this framing (and perhaps your own goals defined), here are questions we’ll explore throughout the rest of this chapter:

What supports thriving and well-being?

Where are the major plots, in and out of schools? Where is the story headed?

Who’s benefiting? Who’s bearing the burdens?

How is it all connected?

These are big questions with big answers, so let’s get started.

What Supports Thriving and Well-Being?

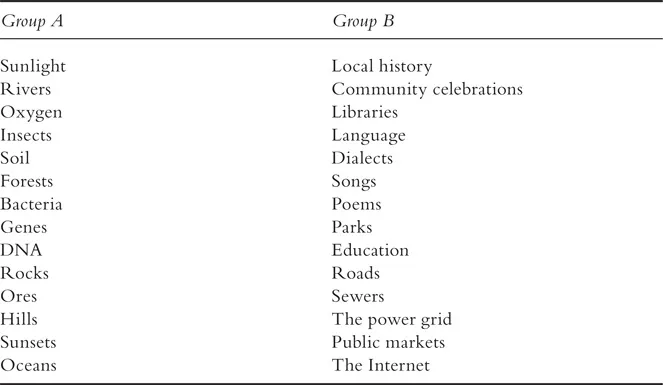

Let’s start with an activity. Review Table 1.1, noting the difference between the items in Groups A and B. If you said that Group A items are from nature and that those in Group B are human-created, you are correct.

TABLE 1.1 What Supports Our Well-Being?

Copyright 2011. Creative Change Educational Solutions. Used with permission.

The Commons

Together, the elements in the table are examples of the “Commons,” the shared ecological and cultural gifts that support well-being (Rowe, 2013). The ecological/environmental Commons include oxygen, water, sunlight, and other things that sustain life for humans and “more-than-human” beings (Martusewicz, Edmundson, & Lupinacci, 2011, p. 86). The human-created, social/cultural Commons include roads, public education, language, and other elements that contribute to community well-being, locally to globally. Again, this varies by culture; not everyone relies on sewers or formal schooling, for example.

Defining the Commons reveals another important reality: We not only have shared goals, but we share the essentials needed to reach those goals. Explore this more in Activity 1.1.

Activity 1.1. Explore the Commons

Review the two lists again. What else would you add to each? What other Commons contribute to our well-being? (We’ll use “Commons” as a singular noun, e.g., the sun is a Commons.)

Are there items from either list that aren’t needed to thrive? Consider how your answers may vary based on individual needs, cultures, community, or time frame.

Choose at least one term from each list and describe how they work together to support well-being. Examples: oceans and sunsets (from Group A) can inspire songs and poems (from Group B). Generate as many connections as you can. (Optional: Write each word on a separate sticky note or file card; use a different color for each list if possible. Then arrange the individual items into clusters or webs to show the connections.)

After you’ve generated your connections, remove a few items from your cluster. For example, if you connected sunlight, soil, roads, and public markets, toss out soil or roads. What happens to the rest of the cluster?

Bring it outside: Take a quick tour around your campus or neighborhood. What are examples of ecological and cultural Commons? How do they work together?

Interdependence

The relationships among the Commons as uncovered earlier illustrate our next concept: interdependence. Our well-being depends on healthy relationships between ecological and social systems. Humans are animals, and we are every much a part of the environment as the polar bear. And while we might not recognize it (yet), everything humans make takes materials out of the environment and puts wastes back into it. This is not a tree-hugger view of the world: It’s the ironclad laws of nature, as we’ll explore later. As you can see, humans are not the only species that matter. If we are to thrive, so must everything else. Going forward then, our definition of “community” will include not only people but also the elements and relationships innate to the Commons. We will study what’s really there: connections and systems, not merely components that exist independently (Meadows, 2008).

Understanding the basics of the Commons equips us to tackle a more layered question: To what extent is the way we’re doing things moving us toward the Story We Want while also sustaining the shared ecological and cultural gifts the story depends on? This is the yardstick we’ll apply to assess whether we’re headed in the right direction. With this tool in hand, let’s think about some of the “plots” unfolding in the world today.

Where Are Major Plots In and Out of Schools? Where Is the Story Headed?

To put the present in perspective, let’s take a quick look back to a historical turning point that launched the “modern” world of today: the Industrial Revolution (about 1760). Industrialization introduced profound social and economic changes: the advent of large-scale manufacturing and agriculture; sweeping medical advances; cars, planes, refrigeration, and other technologies that reshaped everyday life. This industrialization paralleled dramatic improvements in global life span, literacy rates, and more. Over the same time frame, the global human population swelled from 1 billion to 7.5 billion.

Before we conclude that industrialization inevitably improves well-being for all, let’s remember that this transition and its modern manifestation (globalization) have left many people behind. Moreover, these changes have been fueled by ever-expanding mining, drilling, and deforestation—an “extractive economy” that has degraded the ecological systems it depends on (Hornborg, McNeill, & Martinez-Alier, 2007). Because it’s impossible to separate the economy from human well-being and the environment, we’ll keep them all in mind as we assess global trends.

The United Nations 2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are arguably the most comprehensive set...