![]()

CHAPTER ONE

A people in rebellion

American colonists on the eve of the Revolution shared a common identity that set themselves apart from Britons elsewhere. The New World settlers had forged a society and culture from multi-ethnic elements (English, Dutch, German, Scots-Irish and other Europeans), affected also by contact with native Americans and African slaves. A sense of destiny beckoned from the lure of a spacious frontier. The recent victory in the French and Indian War, the culmination of a long duel for a continent, left impressions of pride and invincibility. If challenged to defend against external encroachment upon their liberties, Americans were capable of translating their commonality into independence and union.

A revolutionary movement for the repudiation of parliamentary authority had formed during the decade since 1763. Protest forced the British government to retreat from levying taxes upon the colonies. Parliament, though insisting on plenary power in America, conceded to demands of the colonists to refrain from internal taxation and eventually also external taxes for revenue. Without new provocation the patriot cause seemed on the decline. But new parliamentary measures, in response to American reaction to the Tea Act of 1773, triggered a war.

“An Act to allow a Drawback of the Duties of Customs on the Exportation of Tea …” renewed the 3d. tea impost duty (first imposed by the Revenue Act of 1767) and aimed at ensuring a monopoly of tea sold in America by the British East India Company. With inland duties rebated in England, tea could be sold cheaper than before in America, interfering with merchants’ profits made from retailing smuggled tea. Boston rebel leaders now saw the opportunity once again to exploit the “no taxation without representation” issue when East India tea arrived in Boston harbor. The destruction of the tea by a riotous assembly on the night of December 16, 1773 led to a get-tough policy from the home government. Because of the impossibility of fixing culpability upon individuals parliament responded with punitive measures. More than submitting to a levy of import duties, colonists now faced strident curtailment of liberties.

The Boston Port Act (March 31, 1774), to be rescinded only if Massachusetts indemnified the East India Company for its loss of property, provided for the closure of shipping in Boston harbor. The customshouse was moved to Marblehead and the seat of the Massachusetts government to Salem. The British ministry calculated that severe measures against one colony would not arouse hostility from others, given the well-known sectional rivalry among the northern, middle and southern colonies. To compound the harshness of the Port Act, parliament also enacted the Massachusetts Government Act, intended as a permanent reform, which made councillors appointed by the crown rather than elected by the lower house of the legislature, forbade town meetings without approval by the governor other than for the purpose of annual election, and conferred on the governor authority to appoint all judicial and other officials, including sheriffs and jurors. The Administration of Justice Act, considered also one of the Coercive Acts, allowed crown officials indicted for capital offenses to be tried in England or another province. The three laws collectively underscored the far reaching powers of parliament as infringements on the fundamental rights of Englishmen. Edmund Burke, a member of parliament, correctly gauged the issue that would confront parliament as a result of passing the acts of coercion: it was no longer a question of the “degrees of Freedom or restraint in which they [the colonists] were to be held, but whether they should be totally separated from their connexion with, and dependence on the parent Country of Great Britain.”1

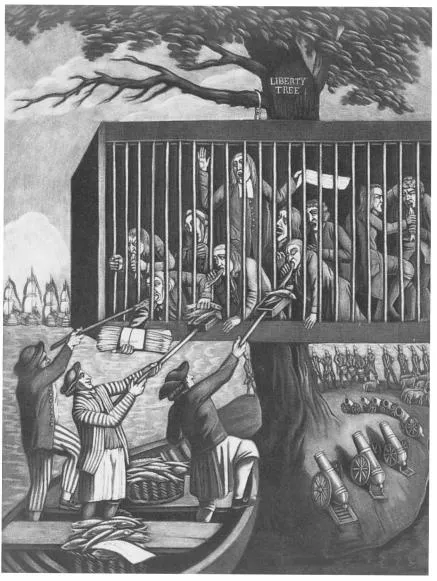

“The Boston Suffering a Common Cause”

Colonists everywhere made the plight of Boston and Massachusetts their own. On June 1, 1774, “being the day when the cruel act for blocking up the harbor of Boston took effect,” many Philadelphians, “to express their sympathy and show their concern for their suffering brethren in the common cause of liberty,” closed their shops and refrained “from hurry and business;” muffled church bells rang throughout the day in the city, crowds attended religious services, and flags of ships in the Philadelphia harbor were hoisted at half-mast.2

The Boston Port Act caused “innumerable hardships.” Provisions and other necessities could only be ferried into Boston by way of Salem or Marblehead, and other goods traveled a round about way by land through Boston neck. Wood boats had to load and unload at Marblehead. The inconveniences added to the price of commodities. “Our wharfs are entirely deserted,” complained a well-to-do Boston merchant; “not a topsail vessel to be seen there or in the harbor, save the ships of war and transports.” It was “no uncommon thing to hear the carriers and waggoners,” who brought goods in by land, “when they pass a difficult place in the road, to whip their horses and damn Lord North.”3

The interruption of commerce at Boston put mariners and laborers out of employment. Propertyless and as wage earners, these underclass workmen, one fourth of Boston’s population, did not have the resources for survival as did merchants and established artisans. The Boston town meeting on May 13, 1774 formed a Committee of Ways and Means, which along with the Overseers of the Poor, was charged with finding aid for the newly unemployed. The Overseers of the Poor, after a few weeks, won exemption from this responsibility since they already had the burden of caring for the regular indigent. Thus the town government revamped the Ways and Means Committee into a Committee of Donations, which had the primary functions of receiving aid sent to Boston and establishing a work relief program. The Committee of Donations interviewed applicants for eligibility for public assistance. From funds obtained, the committee put the new welfare recipients to work repairing roads, making bricks at a new brickyard, cleaning docks, building wharfs and houses, and digging wells for use at fires. Moneys were also spent to set up looms for spinning and to buy materials to supply ropemakers, blacksmiths, and shoemakers. Some of those in the relief program complained because they had “to work hard for that which they esteem as their right without work.”4

New England towns quickly came to the aid of “the industrious poor” in Boston, sending grain, sheep, cattle, codfish, and money. “United we stand—divided we fall,” declared the New Hampshire Gazette of July 22, 1774. “Supplies of provisions sent from all the Colonies are pouring into Boston for the support of the suffering poor there,” wrote Reverend Ezra Stiles of Newport, Rhode Island. “All the Colonies make the Boston Suffering a common Cause, and intend to stand by one another.”5 The Continental Congress several months later resolved that “all America ought to .contribute towards recompensing” the people of Boston “for the injury they may thereby sustain.”6

Substantial contributions flowed from local committees in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Because of the difficulty of bringing commodities to Boston, goods were auctioned on the spot or carried to a New England port such as Providence and converted into cash or bills of exchange to be forwarded to Boston. Typical of cover letters accompanying gifts to the Boston Committee of Donations was that of a Bucks County, Pennsylvania committee, giving notice that it had resolved “That we hold it as our bounden duty, both as Christians and as countrymen, to contribute towards the relief and support of the poor inhabitants of the Town of Boston, now suffering in the general cause of all the Colonies.” Philadelphia Quakers sent a total of £3,910 2s. Much of this money was dispensed among the some 5,000 refugees who had escaped to rural towns, thus enabling them to purchase food and firewood.7

Figure 1 “Bostonians in Distress.” A London cartoon depicts Bostonians caged because of the closing of the city’s port in 1774. The nearly starving inhabitants are fed codfish supplied from neighboring towns. Library of Congress.

Southern colonists joined in the relief effort for Boston. Baltimore sent rye and bread, and Queen Annes County, Maryland, one thousand bushels of corn. Twenty Virginia gentlemen at Williamsburg subscribed £10 each, and Alexandria, Norfolk, and at least nine Virginia counties gave assistance. The German and Scots-Irish farmers of Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley sent many barrels of flour along backcountry wagon roads to Alexandria for shipment. Elsewhere in Virginia, Chesterfield County collected 1,426V2 bushels of grain, and Henrico County provided a shipload of provisions. Fairfax County pledged £273 in specie, 38 barrels of flour, and 150 bushels of wheat “for the benefit and relief of those (the industrious poor of the town of Boston) who by the late cruel act of Parliament are deprived of their daily labour and bread … to keep that manly spirit that has made them dear to every American, though the envy of an arbitrary Parliament.” Settlers in the Cape Fear region of North Carolina dispatched a sloop loaded with provisions; South Carolina supplied several cargoes of rice, and from Georgia came 200 barrels of rice and £122 in specie.8

The gifts to Boston were gratefully acknowledged by the Committee of Donations, which used the opportunity to stress the mutuality of interests of all colonies in condemning the victimization of the people of Boston by the British Coercive Acts. Even before resistance hardened, Americans united in sympathy.

Organization for Resistance

The united effort in providing material support for the citizens of Boston paved the way for the exercise of the popular will in the displacement of the established political authority in the royal and proprietary colonies. Massachusetts set the example by taking actions in violation of the Massachusetts Government Act. Town meetings convened in its defiance. Councillors and other officials appointed under the new system were intimidated to prevent them assuming office. Massachusetts also took the initiative to inaugurate an economic boycott of British goods.

On June 5, 1774 the Boston Committee of Correspondence, which had been in existence since 1772 when created by a Boston town meeting, drew up a Solemn League and Covenant, calling for merchants to pledge not to import British products after October 1, 1774. Many Massachusetts towns soon followed suit. Nine of 12 Massachusetts counties by the end of summer 1774 held county-wide conventions which issued declarations of rights and affirmed a boycott. A convention of Worcester County in late August proposed the convening of an extralegal Provincial Congress to act in place of the regular legislature. Mobs prevented holding sessions of the courts of common pleas and general sessions at Worcester, Springfield, Great Barrington, Taunton, and Plymouth.9

Mass meetings for the purpose of protesting against the Coercive Acts appeared throughout the colonies. In New York City, May 16, 1774, a large gathering voted to name 51 citizens “to be a Standing Committee” to correspond “with our sister Colonies,” to take such “constitutional measures” for “the preservation of our just rights,” to maintain the “public peace,” and to support the formation of “a general union … throughout the Continent.” A Committee of Mechanics, consisting mainly of craftsmen, pressured not too successfully the conservative Committee of 51 toward radical action. No effort was made to install a boycott, the matter being left to a general congress in the future. The Committee of 51 continued to direct the revolutionary movement in New York until spring 1775, when it was replaced by a committee of 60 persons, and then by another one of 100 members, and ultimately by a Provincial Congress. On July 19, 1775 a mass meeting in New York City elected delegates to a Continental Congress.10 A large assemblage of Philadelphia citizens on June 18, 1774 gathered in the State House yard and chose 43 persons as a committee, which met in Carpenters Hall and adopted “six spirited resolves” denouncing parliament’s usurpation of power. Mass meetings at Annapolis and Baltimore, Maryland, in May 1774 resulted in the establishment of committees of correspondence and a call for an economic boycott of Great Britain.11

During spring and summer 1774 seven colonies held provincial conventions or congresses. Virginia led the way in the use of a colony-wide convention to garner power away from the legislature, which would be similarly accomplished by other colonies in creating provincial congresses. When the Virginia General Assembly approved a resolution for observing a fast day on June 1 to show sympathy for the plight of Boston, Governor Lord Dunmore dissolved the legislature on May 26. The next day 89 of 103 burgesses met at the Raleigh Tavern in Williamsburg and proceeded to condemn the Boston Port Act and British taxation and to recommend a boycott of “all Indie goods and whatsoever but saltpetre and spice.”12 A committee of correspondence was formed to keep in touch with actions of other colonies and to promote the creation of a general congress. On May 30 a rump meeting of burgesses called for a convention representing all the colony to be held on August 1. The first Virginia convention met August 1–7 at Wilhamsburg, with delegates from 60 of the 61 counties. The convention adopted complete non-importation to begin November 1 and, if this did not produce redress from the British government, also non-exportation commencing August 10, 1775. Counties were ordered to appoint committees to enforce the boycott and to keep merchants from raising prices. Delegates were elected to serve in the Continental Congress.

Maryland had the distinction of holding the first Provincial Congress, June 22–6, 1774, with 92 delegates from all the counties; trade relations with Great Britain were broken off, and delegates to a Continental Congress were selected. In July New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey followed with similar action. Seventy-one representatives from most of North Carolina’s counties and boroughs met on August 25–7 at New Bern and decided to boycott East India tea immediately and other British goods after January 1, 1775; no slaves were to be brought into the colony after November 1, 1774.13

In Charleston, South Carolina’s influential citizens, many of them members of the Common House of Assembly, had met periodically since 1773 to review British measures. From this arrangement came a meeting of a General Committee of 104 persons from the ranks of merchants...