1.1 Branding the Modern Family: 1950s and Now

After it premiered on the American Broadcasting Company (ABC) in September 2009, Modern Family was quickly declared a game changer, especially because the family sitcom as a subgenre had gone missing and was presumed dead. Some of the praise for the writing team’s skill at telling interlocking stories about three families within a larger extended family was tempered after “Game Changer” (1.19) aired in 2010. The episode has been critiqued for being a program-length commercial. At its center is a product integration story arc about the desire of forty-something suburban “doofus dad” Phil Dunphy to acquire an iPad on the day Apple released the tablets. The comedy comes from the fact that it is also Phil’s birthday, which gives the early adopter great joy and then becomes the situation that delays Phil’s gratification until the end of the episode. The comic mishaps begin after his wife Claire decides that she should be the one to wait in the pre-dawn line at Apple store. The episode ends with Phil’s loving tribute to his iPad, the perfect endorsement for Apple’s new tablet. While Kevin Sandler has written a compelling analysis of the product integration dynamics of the episode, I want to consider the related issue of how the product integration functions as a form of character differentiation of Phil as “the early adopter” willing to try out new tech devices and later trade in barely worn-in products for even newer models. Phil is emblematic of an audience desired by advertisers. He is part of what I call the “think young” consumer cohort, an adult who uses his acquisition of the latest trendy tech devices to signal his youthful self-perception. The “think youngs” have been targeted by advertisers at least since Pepsi coined its 1961 tag-line for those who think young. As part of this consumer cohort, Phil is an adult who consumes like an adolescent because he desires to be seen as much younger than the age listed on his driver’s license.

Modern Family also introduces the related concept of the peer-ent, a term Phil uses to describe himself and his act like a parent, talk like a peer parenting philosophy. The writers use the line, like many in the series, for some good-natured fun at Phil’s expense, particularly for his desire to be an honorary member of the millennial generation. In consumer terms, Phil is a character who is more embraced than mocked. Modern Family favorably represents him as an early adopter and, thus, flatters those who see themselves as part of this consumer group. By categorizing Phil as a “think young,” we can modify his motto into earn like a parent, and spend like a teen, thereby, drawing attention to the general validation in U.S. consumer culture of the “think young” worldview.

FIGURE 1.1 Act like a parent talk like a peer counsels Modern Family’s Phil Dunphy, but his “peer-enting” is not working on his teen daughter Haley.

A sequence in “The Incident” (1.4) connected to Phil’s initial coinage of the term “peer-ent” captures how he is both the peer-ent whose parenting tips are gently mocked and the “think young” consumer type whose spending habits are validated by the sitcom and its corporate underwriters. Two discontinuous beats establish that Phil and his eldest daughter Haley use the same MacBook style laptops, visually signaling their mutual belonging in the “think young” consumer cohort. Phil’s youthful self-conception prompts him to decide to have a talk with Haley about her frustration with Claire’s rules. Before doing so, Phil explains in direct address to the camera in the series’ pseudo-documentary insert sequences that the secret to his closeness with his kids is his peer-enting philosophy: act like a parent, talk like a peer. After a cross cut from the faux interview insert, a shot frames Phil as he is about to enter Haley’s room where she sits up on the bed with her open laptop. The cross cut returns to the direct address sequence in which Phil explains that he learned peer-enting from his dad, who initiated father-son talks with, “What’s up sweathog?” The reference is to Welcome Back, Kotter, ABC’s late-1970s tween-inclusive sitcom with an emphasis on the peer-enting style of a Jewish high school teacher.1 Striking what he clearly thinks of as a “chillaxed” pose, Phil enters Haley’s room and flips her desk chair around so he can sit on it backwards. Casually leaning forward, he suggests to Haley that they should talk to each other, “like a couple of friends kicking it in a juice bar.” The comic beat comes from Haley’s confused interjection, “What’s a juice bar?” Phil begrudgingly modifies his statement, “Okay … a malt shop … whatever.” Still, he believes she is accepting him as a peer until she ignores him to answer a cell phone call and then tells her friend she isn’t doing anything important, “just talking to some dork I met in a malt shop.” The reaction shot of Phil is one of many that gently pokes fun at him. Yet, such sequences encourage empathy for Phil mixed in with the laughter at his humorous miscalculations. His goofiness is also tempered by the conservative dynamics of the series, which imply that he is ultimately a good dad and an even better provider who can support a stay-at-home wife and three children, seemingly with plenty of time to spend with his three kids and money to spend on himself and them.

Phil Dunphy’s characterization is definitely of a 21st-century “think young” peer-ent, but an earlier iteration of the type existed in the 1950s in the sitcom persona of Ozzie Nelson. In accounts of 1950s culture, Ozzie Nelson is more typically described as the Father Knows Best-style father and icon of conservative containment culture.2 I argue against such characterizations, and demonstrate that Ozzie’s television persona embodied the original “think young.” As producer, director, and writer of The Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet (ABC 1952–66), Nelson leveraged the brandcasting potential of the then young medium of television. The former big band leader and his “girl singer” wife Harriet starred in this sitcom with their two sons, David and Ricky. For the purposes of this chapter, I want to focus on how Ozzie Nelson turned his whole family and then each individual member into brand representatives not only of “The Nelsons,” but also of Hotpoint, Coca-Cola, Kodak, and a host of other corporate underwriters of the sitcom. The ways in which Nelson innovated the integration of brands into the story space over the series’ fourteen-year run on ABC is instructive, not only for how sponsorship worked in 1950s sitcoms, but also for how current strategies have their origins in Nelson’s early experiments in the use of the new medium as a brandcasting platform.

Starting with Ozzie & Harriet as a case study, this chapter explores the brand-casting that occurred at the series level in the 1950s and early 1960s through corporate underwriting of some of the costs of television programming. The chapter ends with an analysis of product integration on ABC’s The Middle, to demonstrate that branded entertainment of the present is not a millennial development. Rather, it is a return to the dramatized advertisements and sponsor entwinements pioneered by Ozzie Nelson and other 1950s television producers working in the single and alternating sponsorship financing models.

One of the reasons why Modern Family offers product integration modes of characterization is that the rules of the game of broadcast advertising have changed dramatically. In what television scholars call “the classic network era,” sitcoms garnered the kind of high ratings which networks could leverage to convince advertisers to pay a premium to put their products in front of all those “eyeballs.” In this system, networks staged upfront presentations at which they would pre-sell the projected audience attention to the 30-second commercial spots that played in story breaks as part of “magazine concept” advertising (a.k.a. participating advertising). Although many factors contributed to the decline of the effectiveness of the 30-second spot, and hence of broadcast advertising, it is easy to point to the invention and then broad adoption of DVRs, among other timeshifting technologies, and the availability of placeshifting devices such as iPad tablets. Whatever the exact mixture of complex factors leading to this broadcast ratings decline, American companies who had been buying time on broadcast television were worried about the effectiveness of traditional spot advertising. Networks began to offset their anxieties with various kinds of branded entertainment deals.

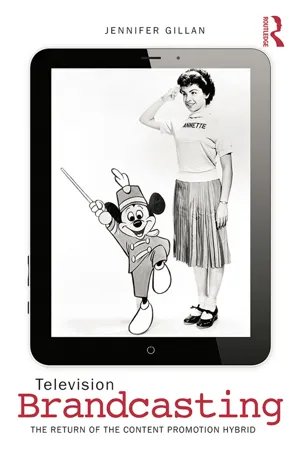

I detailed some of the recent deals in my earlier book, Television and New Media: Must-Click TV. I looked at the creative product integration strategies on NBC series including 30 Rock and The Office.3 In Television Brandcasting I am more interested in demonstrating that these strategies only seem new because they are a departure from classic network-era strategies. They are actually a return to the content–promotion hybrid strategies utilized in midcentury American television programming.

Later in this chapter, I consider the dramatized advertisements that were essential parts of the 1950s corporate sponsorship of programming on the era’s new media platform: broadcast television. At the time, television’s function as an advertising platform for corporate products and a circulation platform for corporate self-representations was evident because television personalities of all kinds openly endorsed products. Sitcoms played a particularly important role in this process, not only because sitcom sets could double as product showcases, but also because the stars could stand in or outside of their television homes and recommend particular brands to viewers whom they would directly address as friends in content–promotion hybrids airing after the credits or in a break in the story.

1.2 Sponsored Credit Sequences

The credit sequences of several midcentury series establish a now common consumerist and aspirational representation of the American family on television. In them, images of families posed as if for official portraits are entwined with product endorsement: the all-male family of My Three Sons for Hunt’s Ketchup and Chevrolet, the nuclear family of Leave It to Beaver for Plymouth and Ralston-Purina, the mother knows best family of The Donna Reed Show for Campbell’s Soup and Singer Sewing machines, and, most significantly, “America’s Favorite Family” from The Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet for Coca-Cola and Kodak. The Nelsons were definitely the sponsors’ favorite family as they had willingly entwined their television personas with the suburban family messaging of several corporations starting with Hotpoint, a General Electric division. As series producer, Ozzie Nelson integrated Coca-Cola into scenes set at his television family’s backyard cookouts and teen parties, and shot a variety of dramatized advertisements for Kodak. One of the more significant ones featured Harriet Nelson as a trusted advisor to new suburbanites to whom she recommends the practice of home videography as a way to both preserve memories of family fun and togetherness and to promote a desired self-representation. Before turning to an analysis of Ozzie & Harriet’s precedent-setting sponsor entwinements and an evaluation of those strategies over the sitcom’s 14-year run, I first establish how industrial time (e.g., commercial and promotion spots) is blocked off, segmented, and sold in the U.S. television industry. I then consider why star sitcoms were so effective at conveying consumer advice to viewers. Finally, I discuss why “typical American,” suburban sitcoms became the preferred sponsor-vehicle by the end of the 1950s.

Branding, not entertainment, is the main imperative of television as an industry. In the classic network era, broadcast television typically employed participating sponsorship, or magazine concept advertising (a variety of spots and sponsors), making branded entertainment of the 2000s (e.g., Ford’s 24 and Maybelline’s Lipstick Jungle) and product integration deals (e.g., Hiro and Ando’s Nissan Versa on Heroes) seem new. Yet, these sponsor strategies actually are some of the oldest in the U.S. TV industry. Corporate sponsors shaped the look of 1950s television schedules, often exerting pressure on networks and producers to offer them programming that provided an appropriate context in which to place or integrate their products.4 By the mid-1950s, s...