![]()

Chapter 1

From diagnosis to clients

Constructing the object of collaborative development between physiotherapy educators and workplaces

Jaakko Virkkunen, Elisa Mäkinen and Leila Lintula

The need for boundary crossing and co-development in professional education

The ongoing change in the techno-economic paradigm

Current developments in Western societies have been characterised by the buzzwords ‘information society’ and ‘knowledge society’. Freeman and Louça’s (2001) and Perez’s (2002) analyses and theories concerning the interplay between technological revolutions and societal development nevertheless give an articulated meaning to these words that helps to further understanding about ongoing transformation in professional and vocational education. According to these theories, a technological revolution takes place when a combination of radical innovations emerges that brings a new, cheap resource into the economy and leads to the creation of a new kind of infrastructure. Water wheels and canals, steam power, electricity and steel, the internal-combustion engine, oil and the chemical industry have been such epoch-making technological revolutions. Currently we are living in a long economic wave based on the information and communications technology revolution.

According to Perez (2005), the surge that starts from a technological revolution has two qualitatively different phases. In the first, the installation phase, flexible financial capital is invested in the industries directly connected to the new technology. The new technology is developed and new infrastructures based on it are built, but it is still applied in a limited way because its use is confined by the existing institutional structures. This phase typically ends with the bursting of the financial bubble of overinvestment in the new technology. Then the second phase starts, involving general deployment. The driver in this development is industrial capital, and the new technologies are used throughout the economy and society to reform the way in which activities are carried out. Gradually the techno-economic paradigm is transformed. New ideas about organisation, management, effectiveness and efficacy emerge and become the self-evident common sense of the era.

According to these authors the installation phase of the ICT-based surge of cheap information started in the early 1970s. The transformation of the techno-economic paradigm has, however, only become speeded up since the 1990s. The long period of economic growth after the Second World War, which lasted until the 1970s, was fuelled by the triumph of the techno-economic paradigm of the ‘motorisation wave’. This in turn was based on cheap energy and transportation, and was characterised by the application of

• mass production and mass markets;

• economies of scale (product and market volume);

• product standardisation;

• functional specialisation/hierarchical organisation;

• centralisation.

The application of economies of scale and centralisation led to increasing complexity in work organisations. The resulting increase in the need for coordination was counteracted through the creation of semi-independent units, sharp divisions of labour and standardisation in products and processes.

The emerging new techno-economic paradigm of the global ICT and hightech economy, according to Perez (2002: 18), is characterised by

• globalisation, interaction between the global and the local;

• decentralised integration and network structures;

• knowledge as capital and intangible value added;

• adaptability, heterogeneity and diversity;

• the segmentation of markets and proliferation of niches;

• economies of scope and specialisation combined with scale;

• inward and outward cooperation and the formation of clusters;

• instant contact and action, instant global communications.

The new information and communication technologies make it possible to coordinate complex systems real-time, which leads to the integration of functions and activities that earlier had to be separated. The increasing importance of scientific and technological knowledge and innovation, on the one hand, and the segmentation of markets on the other, increase the need for continuous innovation and the application of scientific and technological inventions in various fields of activity. It is also clear that traditional ideas about occupations, qualifications and careers are losing some of their relevance in the new conditions.

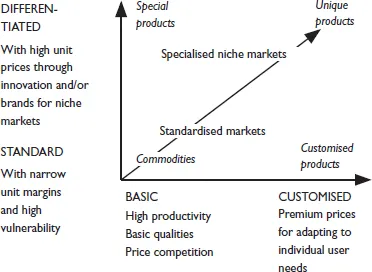

According to Perez (2005: 24–25), the structure of economic activities in the developed Western economies is changing as a result of changes in the international division of labour and re-specialisation triggered by the technological revolution and globalisation. The changes take place not so much on the level of whole industries as on the level of functions and activities within them. The trend is from the production of standardised basic commodities to the production of specialised, unique or customised products. These forms of production are knowledge- and information-intensive, although in different ways (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Tendencies of change in the nature of productive activities in the developed countries (adapted from Perez, 2005: 24–25)

The transformations of vocational education

The structures and conceptions of vocational education have changed with the changes in economic activity and the techno-economic paradigm. Until the late 1970s it was seen in Finland as part of the respective industries. It was carried out in educational institutions that were tightly connected to the industries and organisations that employed the qualified workforce they produced. In the major reform of middle-level vocational education that started in 1978 college education was moved from the industries to the school system under the Ministry of Education. The curricula were standardised and broadened in order to give the students qualifications that gave them occupational mobility and opened the door to further studies. A conceptual distinction was made between broad ‘educational occupations’ and the actual jobs in working life. ‘Educational occupation’ was a generalisation concerning the kinds of jobs for which an educational programme was supposed to qualify the students.

The reform, which was consolidated in 1987 through new legislation, could be seen as the late completion of the adaptation of vocational education to the techno-economic paradigm of mass production. This paradigm affected vocational education in two ways: first, through the specific concept of the object of vocational education; and second, through the application of the principles of mass production to educational work.

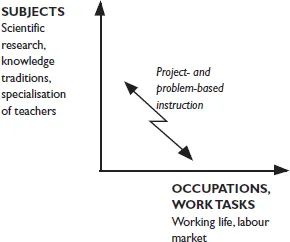

In mass production work is divided into standardised jobs, the content of and necessary qualifications for which are standardised and defined for long periods of time. Job descriptions and the specification of qualifications was therefore the natural starting point of educational planning in the era of mass production. The competences to be produced were derived through the definition of statistically typical tasks and related competences in a class of jobs. Although there was strong pressure to focus on task qualifications in the training, it was difficult to organise curricula on the basis of tasks (Young, 2004): it was easier to divide the curriculum content by subject (Figure 1.2). Attempts have been made to integrate task- and subject-based teaching through problem and project-based instruction (Kilpatrick, 1918; Wilkerson and Gijselaers, 1996). However, the ideas of occupations and generalised job descriptions, task competencies and task-based planning have remained at the core in the planning of vocational and professional education.

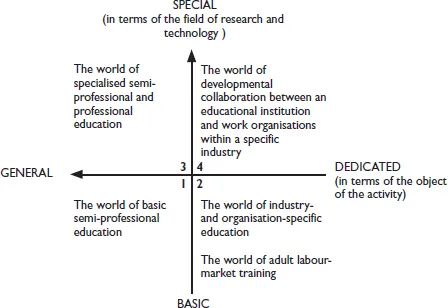

Globalisation and the information-technology revolution have brought somewhat contradictory challenges to professional education. First, globalisation has increased the pressure to standardise degrees and curricula internationally, and to make it possible for graduates to move in the labour markets over national borders. Second, new technologies and new scientific knowledge are playing an increasingly important role in a growing number of occupations while the number of traditional middle-level occupations decreases. Third, the drastic changes taking place in labour markets are creating the needs for qualified personnel in new areas. On these grounds we might assume that the traditionally unified concept of professional education is gradually becoming diversified along two dimensions. The first of these, from basic to specialised education, represents the traditional conception of vertical expertise. It differentiates between basic professional competences on the one hand, and, highly specialised and specific competences related to a specific field of research, a specific technology, or specific methods (sometimes developed in a certain organisation) on the other. The other dimension, from the general to the dedicated, represents the horizontal aspect of expertise. It differentiates between competences that meet the needs of a broad array of specific occupations and those that are based on a broad understanding of a specific activity and cross-professional collaboration in specific industries and organisations. It distinguishes, for instance, between a general nurse and a nurse specialised in care of the elderly, and between a general engineer and an engineer specialised in road building.

Figure 1.2 Project- and problem-based instruction as an attempt to solve the contradiction between subject and task as the basis for curriculum organisation

Professional education is always based on forms of collaboration and interaction between working life and educational institutions. Therefore, following Storper’s (1996) idea, when speaking about different concepts of professional education we also have to consider the different ‘worlds’ of education in the sense that each one has its culturally developed conventions, concepts and practices of managing the interaction between education and working life (see Figure 1.3).

In Finland, the first great reform of middle-level education between 1978 and 1987 moved it from the world of dedicated basic education (field 2 in Figure 1.3) to that of general basic education (field 1 in Figure 1.3). Over the years, a need for dedicated basic education of adults has developed and intensified as the number of unforeseen rapid changes in labour markets has increased (field 2 in Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Four worlds of semi-professional and professional education

A new reform of semi-professional and professional education started in Finland in 1990. As a result, various colleges were combined into large units and the levels of both the education and teacher qualifications were raised. The new institutions, called ‘polytechnics’ or, as those involved prefer ‘universities of applied sciences’, were given the task of carrying out research and development activities that support education, the development of working life, and the general regional development in their geographic areas. They are now developing a new kind of education that differs from both traditional college education and university education.

This recent reform moved the education in polytechnics from the world of general basic education to that of general special education (field 3 in Figure 1.3). Both this and earlier reforms have increased the distance between education and working-life organisations because of the increasing generality of the competences to be produced and the specialisation of teachers. There is an aggravating contradiction between both task- or occupation-based and subject-based education on the one hand, and the rapid development of forms of production as well as the increasing knowledge-intensity of work on the other. The dynamics of ongoing change in work activities and the emerging developmental possibilities inherent in them cannot be seen by just focusing on occupations. An understanding of the historical development, the current developmental challenges, and ongoing transformations in forms of production is increasingly needed.

In knowledge-intensive production, various specialists are increasingly expected to be active in defining the tasks and content of their work, and in showing how their theoretical knowledge and the methods they use can be applied in a certain context. In this sense, the tradition of analysing the relationship between education and working life mainly in terms of occupations and tasks is a hindrance to developmental collaboration between working-life organisations and polytechnics. Such developmental collaboration can best take place in a world of dedicated special education (field 4 in Figure 3) in which education and the research and development of the work activity are combined. The challenge is to create a new kind of dedicated education based on the application of theoretical knowledge in the development of a specific productive activity or solving an emerging societal problem. An important element in such education is a specific form of collaboration between the educational institution and a work activity, which Tuomi-Gröhn and Engeström (2003) called ‘developmental transfer’. This means that theoretical generalisations are transferred and applied in dialogue and negotiation within sustained developmental collaboration between an educational institution and a set of work organisations.

In the following we describe a Change Laboratory process in which the teachers of one department in a polytechnic took a major step towards the world of developmental collaboration with working-life organisations through developing a more dedicated educational approach.

The Change Laboratory in the Department of Physiotherapy Education at Stadia Polytechnic

The Change Laboratory method

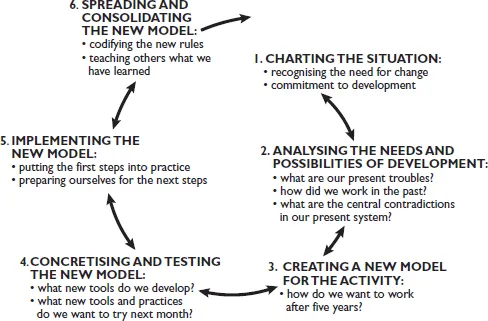

Change Laboratory is an activity-theory based intervention method for supporting expansive learning in work communities (see Engeström, 2007). The basic idea is that the work community engages itself in a process of analysing the form and development of its activity. The aim is to reveal the systemic causes of the problems individuals experience in their daily work and to collectively design and implement a new form of activity that is based on a re-conceptualisation of its object and purpose. The intervention method is based on the use of first-hand data about the activity, which is analysed by means of various conceptual tools, principally a general model of an activity system and a model of the phases of expansive collective learning in an activity (Engeström, 1987). The interventionist initially helps the work community in its learning activity by organising the collection of data that mirrors problematic aspects of the current practices and the historical development of the activity, by defining the tasks of analysing and designing, as well as acting as a facilitator in the intervention sessions. The Change Laboratory process typically consists of ten two-hour sessions once a week or fortnight, which leads to a period of experimental changes of practice. The phases of the process are depicted in Figure 1.4.

Figure 1.4 The phases of a Change Laboratory process

Turning points in the Change Laboratory process at the D...