![]()

Part 1

A useful guide to ICT in the

classroom

Introduction

In Part 1, we look at issues common to the use of ICT, both in the classroom and on educational trips. A brief review of relevant literature is followed by a look at how ICT can be used to develop both pupil and teacher creativity. Inside the classroom, we look at the potential that interactive whiteboards (IWBs) have for making lessons dynamic and engaging in new ways. Not all schools use their computer facilities intensively, and computer suites are often the easiest places to find a quiet, unused room in a school. Even the standalone computers can be isolated and unused. In this book, there are suggestions for making better use of both standalone and suites of computers. E-safety has had its profile raised, thanks to the Byron Report (2008), and some of the main points are outlined here. This is followed by sections on how to develop good practice in finding digital information, communicating using e-mail and other Internet facilities. The section on using ICT outside the classroom looks at a range of hardware and software that may be useful on class trips and residential visits or just around the school grounds. The section on assessment tries to simplify the process, showing how ICT can be used for planning further learning as well celebrating success. Assessment should not be excessively time consuming, and developing e-portfolios is a natural development of this work. Finally, we look at the use of ICT in a teacher’s professional role and how it can help to reduce the burden of planning, teaching, assessing and record keeping. There are case studies to show how some of these ideas can be implemented in good practice.

![]()

1 Creativity and ICT

In this chapter we will explore:

- what we mean by creativity;

- questioning and challenging;

- making connections and seeing relationships;

- envisaging what might be;

- exploring ideas and keeping options open;

- reflecting critically on ideas, actions and outcomes;

- challenges to develop creative skills.

Whose creativity?

Creativity was listed briefly as a skill to be encouraged in the first National Curriculum (NC) in 1989 and was, for some time, subsequently considered mainly in artistic contexts by educators. By the time of the New Primary Curriculum (NPC), which was published and withdrawn in 2010, creativity had been extensively discussed, defined and identified as a key skill to develop in all pupils and in all subject areas. Creativity was given major consideration in both the Rose (2009) and Cambridge reviews (Alexander 2009) and featured in all areas of learning in the NPC. The NACCE report (1999) stated that all of us have the capability to be creative if we are given the opportunity and it defined creativity as ‘Imaginative activity fashioned so as to produce outcomes that are both original and of value’. We may not all achieve the creativity of Beethoven or Einstein, but we are all capable of thinking imaginatively, for specific purposes, to create useful and original outcomes. These outcomes do not have to be artefacts, but may be ideas or processes or systems. Creative outcomes may result in discoveries in medicine, constructions in architecture or engineering, new ways to organise roads or logistics, or advances in artistic fields. In the classroom, this might start as discovering the best way to lay out a brochure using a word processor; finding ways to solve a maths problem with a calculator; using a graphics package to redesign parts of the school grounds; composing a jingle on an electronic keyboard for an advert; using a spreadsheet to organise a budget; or creating a digital gallery of pupils’ work for parents and friends to see.

It would be useful to discuss with colleagues what is meant by the term creativity, as many people believe it to be an arts-related skill, most often exhibited by someone wearing a French beret. See research from Bath Spa by Davies et al. (2004) to confirm this, or ask your friends to draw their idea of a creative person. Very few are likely to show a computer being used.

In 2004, the QCDA produced materials to help teachers identify and develop the features of creativity in their pupils. The publication, ‘Creativity: find it, promote it’ (2004), stated that, ‘Pupils who are creative will be prepared for a rapidly changing world where they may have to adapt to several careers in a lifetime’ (p. 9).

Using the five characteristics of creativity outlined in this publication, this section will look at ways of using the new digital technologies to develop creativity in a range of educational contexts. Of course, ICT is not the only way to develop creative skills, but the opportunities it affords deserve close consideration. The five characteristics of a creative person identified in this publication (p. 10) are:

- questioning and challenging;

- making connections and seeing relationships;

- envisaging what might be;

- exploring ideas, keeping options open;

- reflecting critically on ideas, actions and outcomes.

Questioning and challenging

In order for pupils to learn, they need to be skilled at asking questions. This is a skill to be taught from the earliest days in school, with children progressing from ‘how?’ and ‘where?’ to ‘when?’ and ‘why?’ and on to ‘what if?’ and ‘how can?’. All questions should be acknowledged as being of worth, and ways to help the questioner to answer them should be identified.

Questions can be answered using the acronym AREST, as shown in the box.

Digital technologies can be used in many contexts, with each of the above techniques, though they may not help to answer every question that a thoughtful child might devise.

In KS1, children posing questions such as ‘How do some seeds cling to clothes?’ could be helped to find the answer by putting the burrs of goosegrass or burdock under a digital microscope or visualiser, in order to see how the burrs attach themselves to different types of fabric. Challenges such as ‘Do I live nearer to school than my friends?’ can be answered with a look at Google or Google Street View. Unusual questions such as ‘What if there was no blue in the world?’ might be checked out by taking the blue out of digital photos.

Children in LKS2 might want to know ‘What did the Vikings have for breakfast?’, and research using a CD-ROM or the Internet could help to answer this and similar factual questions. The Internet could also provide some of the prices and information when a class tries to discover ‘Which animal would make the best pet?’. They could consider the exercise and cleaning routines and record initial set-up costs and weekly care expenses on a spreadsheet. Charts from the latter could be combined with their research results into a multimedia presentation. To see if a story would be more exciting in the past or present tense, it would be simpler to redraft using a word processor than by hand.

Asking someone who might know the answer can be done through e-mail, texting, webcam, skype, video-conferencing, blogging or social networking in an attempt to find someone who has relevant information.

Researching the answer can be done using the Internet or CD-ROMs.

Experimenting to test ideas through practical investigations, possibly using data-logging to record accurately; modelling to try out ideas; or data-handling software to organise and make charts to help analyse the data.

Simulations, when first-hand tests are impracticable, are available on CD-ROMs and on the Internet.

Thinking around the problem, reflecting on ideas, events and discussions and perhaps recording these reflections using ICT to organise mind maps or just notes and lists.

Older primary pupils in UKS2 are usually very motivated when challenged to design their ideal bedroom/playroom or to redesign their classroom to use the space more effectively. This can be done using the computer-aided design (CAD) room-planning programs from IKEA (www.ikea.com/ms/en_GB/rooms_ideas/splashplanners.html) or just standard graphics tools in Word, Textease or other word-processing (WP) programs.

Once familiar with the technology, they might ask, ‘What if we left the data logger on all night? Could we use the movement sensor to see if the fish in the tank go to sleep at night?’ or ‘If we left the sound sensor on all day, what would we find out about the sound levels in different types of lesson?’. You, the teacher, could then challenge them to see ‘How could we make a quiet but dull place in school more interesting, or a noisy place quieter?’.

Children who are creative will be curious about themselves and the world. They will want to know the answers to questions, will love to dream up the most interesting and surprising questions and enjoy the challenge of answering them. If a teacher knows all the answers to the questions the class is asking, then the pupils are asking very limited and unimaginative questions.

Making connections and seeing relationships

In order to develop original concepts, it is useful to think laterally rather than linearly and be able to make connections between seemingly unrelated objects or ideas. New products or designs are often invented by associating apparently unrelated objects, using the free-association method promoted by de Bono (1976). Classification systems for plants, animals and rocks have been developed through observation of what items have in common and what makes them unique.

To develop this skill in KS1 children, a teacher could present sets of pictures, using clip art or photos on an IWB, and challenge pupils to spot the odd one out. In the case of a cart, a horse and a tree, there are several possibilities, such as: the cart is the only one not alive; the horse is the only one not made of wood; or the tree is the only one that cannot travel. Children will find other interesting explanations for their ideas. To learn more about a story, for example The Gruffalo, and the language it uses, ask your class to make a soundscape for the story, either using a digital music program or else recording percussion instruments on to tape or a digital sound file. This could be added to a reading of the text and turned into a podcast for other classes to share. A class that has recently learned to write simple instructions could use a computer template, with headings and bullet points, to write instructions for a magic spell to make a friend laugh or a recipe to turn their teacher’s hair green.

Figure 1.1 Which layout will suit the class best?

Pupils in LKS2 will find it engaging to communicate their knowledge in novel ways. They could word-process speech and thought bubbles to create cartoons strips to show their understanding of a science concept or a story from RE, or make a digital animated film to record their learning in history or PHSE sessions. Creating analogies and metaphors is another dimension to creative thought, and so the teacher could challenge the class to explain what friendship is like in response to pictures shown on the whiteboard, e.g. a tree, a kitten, a ball, rain, climbing a hill. Answers might be that a friendship is like a tree because it can grow, like a kitten because it is easily hurt, like a ball because it can bounce back when you think you have lost it, like rain because it is refreshing, and like climbing a hill because it can be hard work but worth it. Pupils could create similar puzzles for their friends using clip art, e.g. a school is like . . .; a holiday is like . . .; a story is like . . . These could be added to a class e-zine, virtual learning environment (VLE) or the initial analogy, word-processed as a heading on a wall poster, on which friends can add handwritten ideas.

Older pupils in UKS2 could use concept-mapping software such as Kidspiration to create a mind map to show connections between prior knowledge and recent learning. They could then copy the information and use it to make a digital presentation for parents’ evening or a class exhibition. When searching for patterns or trends to answer the question ‘How can I make the best parachute for my action figure?’, they can use a spreadsheet to record time taken for proto-parachutes of different sizes, shapes and materials to fall, before constructing a final version. They should be taught to present their learning in as wide a range of ways as possible, so that, instead of just writing down what they have learned and completing worksheets, they make digital movies, podcasts, multimedia presentations, word-processed posters and brochures to share with different audiences.

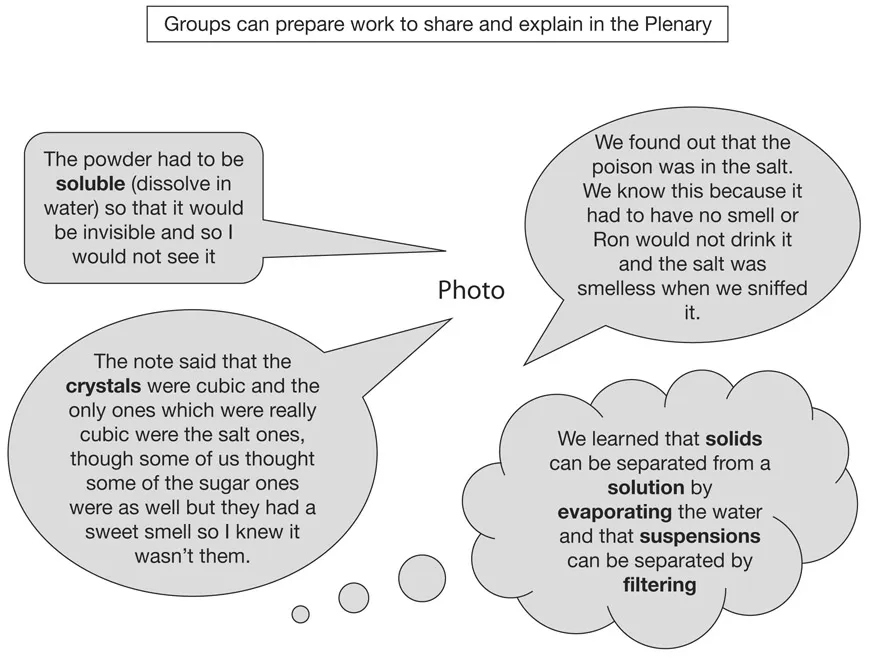

Case study: Using ICT for recording in science

An Advanced Skills Teacher (AST), working with a Year 5 (Y5) class on separating mixtures, taught the subject on a Harry Potter theme. Once the teaching and testing were complete, she asked her class to record their learning for a particular group of readers in a way that would interest them. She reminded them of techniques they had been recently taught in literacy, such as writing instructions and reports, and asked them to work in pairs or small groups on whatever form of presentation they chose. They could use the computers if they wished, and most chose to do this.

Some children word-processed their ideas as a spell for a wizard’s book. One pair of pupils made a concept map on the computer to show their learning and help their friends with revision. Others chose to write the material as an article, using a digital newspaper template, for their parents to read. One group chose to make a PowerPoint presentation to share with another class, and a couple decided to complete the task in verse to amuse themselves. Most groups added digital photos to show each stage of their work. In every case, rigour was maintained by the requirement to use and explain particular key scientific terms. The children were motivated by the diverse possibilities in presentation and cooperated in producing twelve well-presented and explained write-ups, instead of thirty-two, nearly identical test reports. Sharing the results was useful revision for all.

Figure 1.2 What we learned, by Jack, Tim, Laura and Chloe. The final slide from one group’s presentation

Envisaging what might be

An important role of education is to help the learner to see things in new ways and from different points of view; to imagine the possibilities of different situations; and to foresee problems and visualise solutions. A higher-order thinking skill to develop is the ‘What if?’ question.

KS1 children should be helped to imagine and then to see...