![]()

1 The nature of care

Caring is the essence of nursing and the most central and unifying focus for nursing practice.

(Jean Watson 1988)

Introduction

The quotation above is attributable to Dr Jean Watson, and forms part of her theory of nursing. Dr Watson is a distinguished American nurse academic and professor of caring science, who has researched and published widely on the philosophy and theory of human caring and the art and science of caring, particularly as applied to nursing. In this chapter, we explore what is meant by ‘caring’ and consider whether there is a general concept called ‘care’, or whether caring differs in a professional context from the way in which we care for, and are cared for by, our family and friends. By summarising some important research and theories of care and caring, this chapter attempts to uncover and explain the key components of caring. This consideration of the meaning of caring will provide the context for the remainder of the book, in which a specific aspect of care (psychological care) is the focus.

What is care?

Action point

Look in any dictionary and see what kinds of definitions are given for the words ‘care’ and ‘caring’.

The Oxford Popular Dictionary has a number of definitions for care, both as a noun, or thing, and as a verb; something that people do. There is no entry for caring. A nursing dictionary does not list either term. If you found any definitions, these are likely to be along the lines of those in Box 1.1, taken from an online dictionary:

Box 1.1 Definitions of care and caring

Care:

Can be a noun, meaning the work of providing treatment for or attending to someone or something.

Can be a verb, meaning to feel concern or interest.

Caring:

Can be a noun, meaning a loving feeling.

Can be a verb, meaning to feel and exhibit concern for others.

Source: Wordweb online dictionary and thesaurus. www.wordwebonline.com

Within these sample definitions, meanings of care and caring are sufficiently broad as to encompass providing treatment, feeling interested, feeling concerned, and even having loving feelings towards another person or persons. However, there seems to be a world of difference between ‘providing treatment for’ and having a ‘loving feeling for’ someone. This illustrates why it might be difficult to define ‘care’ and ‘caring’ precisely, both in a general context and when we apply the concept of care to professional health care settings.

In the past 30 or so years, the concept of caring has begun to be given serious attention. There have been several published literature reviews, but until recently, relatively few research studies into the meaning of care and caring. One possible reason is that disciplines such as nursing, which have ‘care’ as their focus, have for a long time struggled to establish themselves as professional, scientific disciplines, in which concrete concepts that can be studied scientifically through observation and measurement are valued. Concepts such as caring may have been thought ‘soft’ and therefore inappropriate for scientific study. Nonetheless, in recent years there has been a dramatic increase of interest in the nature of care, caring, and modes of care delivery. This has resulted in an increase in the number of studies setting out to explore caring, an ever-increasing number of theories of caring, and a burgeoning of reports and policy documents in which the concept of care is central. Currently, for example, in England, hospitals and other health care establishments are implementing the ‘Essence of Care’ strategy (Department of Health 2001, 2003), which aims, amongst other things, to improve the quality of ‘the softer aspects of care’ such as communication and ensuring privacy and dignity. We consider Essence of Care and its impact on psychological care further in Chapter 9.

Despite this, there is a widespread view that care is such an abstract and elusive concept as to defy description, and perhaps this might always be the case (Paley 2001). Caring is often taken for granted as something that comes naturally, especially for women (Baughan and Smith 2008). Sometimes, however, we are only really aware of what care is when we realise that it is absent, and it is sometimes easier to think about what care really means by thinking of situations that illustrate poor or absent care. Consider the following case illustrations:

Case study 1: Martin’s grandmother

In September 1997, Martin Bright, education correspondent for The Independent newspaper, wrote an article headlined ‘She was dying for a cuppa. Literally’. He recounted the story of his grandmother who, at the age of 88, had suffered a major cerebro-vascular accident (stroke) from which she had unexpectedly survived, and was transferred to an NHS hospital ward. It was then that her real problems began. Her greatest desire was for a cup of tea, but, it being a weekend, there was no speech therapist available to assess her ability to swallow; without this assessment, no doctor could allow her to have a drink. A series of events ensued over the next few days which Bright variously described as ‘shocking’, ‘a nightmare’, and ‘torture’. A fellow patient was heard to say: ‘It’s broken my heart. They won’t even go near her. She’s been lying there all day and nobody cares’. Eight days after her admission, his grandmother had still not been seen by the speech therapist and had not been allowed to eat or drink (although her nutritional needs were met in other ways). Nursing staff did not appear to feature significantly in her care, the vast majority of which was provided by her relatives. While this patient’s needs for physical care and safety were addressed, there was an overriding sense that many of her other needs were never attended to. The result was an overpowering impression of a lack of care by health care professionals, including nurses.

Case study 2: Ellen

Ellen, aged 82, was admitted to hospital for surgical investigation of what was believed to be a malignant tumour. She had until then enjoyed good health and had little experience of the health services. She had been waiting for admission for several months, and it was with great relief that she finally arrived in the ward in a specialist hospital 50 miles away from her home. Naturally, she was anxious about what the investigations might show; about what treatments she might need; and indeed about whether she would recover from her condition. On entering the ward, she was approached by a health care support worker who asked her to wait in the ward lounge, as her bed was not yet ready. There she was to wait for almost two hours until a second health care support worker came to offer her lunch, as the bed was still not available. Neither of these two carers introduced themselves to her, nor explained the delay. Several hours elapsed until the nurse manager finally showed her to her bed. Once again, no introductions or explanations were offered. It was not until Ellen had been in the ward for over seven hours that an individual made human and personal contact with her, introducing himself by name and role, and giving a full explanation of what was to happen during her stay. Interestingly, this individual was a junior doctor, a member of a professional group that is traditionally associated with ‘curing’ rather than ‘caring’. Yet his actions demonstrated greater ‘care’ than the others whom Ellen had encountered until that point.

Case study 3: Robert

Robert, a fit and healthy middle-aged man, was in hospital for a minor surgical procedure. Upon being visited by his wife on the evening following surgery, his first words were, ‘Thank goodness you’ve come . . . you can help me sit up and use the [urine] bottle’. To which his wife replied, ‘Why didn’t you call someone?’ As soon as these words had been uttered, the answer became apparent. The nurse call bell was hanging neatly in its place on the wall, well out of reach of someone who had that day undergone abdominal surgery, and was still somewhat drowsy and unsteady from the effects of the anaesthetic. An excusable oversight by busy staff? Or evidence again, of thoughtlessness, neglect, and lack of care?

Reflection point

What, if any, deficiencies in care can you identify in each of these stories? Are there any common factors across the stories?

Although in Ellen’s case the lack of an available bed was a resource issue perhaps out of staff control, across the case examples, the patients’ immediate need was for something other than physical or medical care. Their stories have highlighted how easy it is for patients’ needs for comfort, information, reassurance, dignity, and self-esteem to be overlooked. So care seems to be something greater than caring for physical needs, and something which is certainly noticed when it is absent.

Patients’ views of caring

To achieve the best possible care, the perceptions and expectations of health care professionals and their patients ought to agree with one another. In the stories above, we might imagine that carers and patients did not see care in the same way. Hence, we need to be aware of the potential for discrepancy, and to understand possible reasons for it, where it exists.

From research evidence, it appears that there is a discrepancy between professionals’ and patients’ views of caring and the relative weight placed upon particular expressions of caring in practice. Some studies have shown that patients and relatives value highly the more personal aspects of care, sometimes described as the ‘expressive’ elements of caring, such as openness, attentiveness, listening, and forming a bond with carers. Small acts of caring, such as screening the bed of a dying patient, are viewed as important, and when these details are overlooked, distress is caused to patients and relatives (Philpot 2001). It seems that when care is presented to patients in terms of objective, professional tasks such as checking vital signs (temperature, pulse, and blood pressure, for example) or managing pain, patients sometimes have difficulty interpreting this as ‘being cared for’ (Paulson 2004). Classic studies of nurses’ perceptions of caring such as those of Forrest (1989) and Clarke and Wheeler (1992) (reviewed later in this chapter) show that nurses, too, value expressive elements of caring.

However, many studies point to the opposite (Attree 2001). In such studies, patients are found to place more importance on directly observable caring activities or tasks, sometimes referred to as the ‘instrumental’ elements of caring, such as dressing a wound or administering medication, than on the less tangible expressive activities such as being listened to or comforted. In sum, there is a continuing debate about whether carers and patients see ‘care’ as the same thing, and the relative importance each places on the practical, tangible aspects of caring and the expressive, emotional element (Baughan and Smith 2008).

Reflection point

What do you think Martin’s grandmother, Ellen and Robert would have said if you had asked them what care they most needed?

Martin’s grandmother might have said ‘a cup of tea’. Ellen might have said ‘information’. Robert might have said ‘having the call button to hand’. So perhaps they too preferred practical, easily observed attention to their needs over the more expressive elements of care? Or maybe these were their most urgent priorities, needing to be satisfied before they could even think about a word of kindness, a listening ear, some reassurance, or forming a bond with a carer?

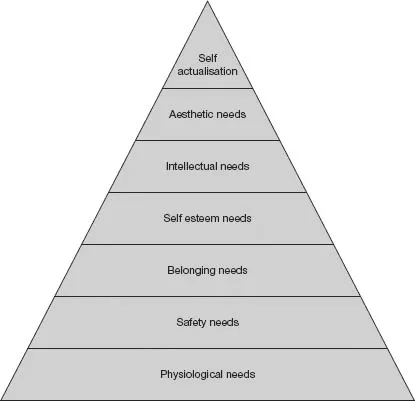

If so, we can understand that at least a minimum level of physical or technical care is required before patients are able to be receptive to the less tangible or expressive aspects of caring (Kyle 1995). This is in line with Maslow’s (1954) theory of human motivation, illustrated as a ‘hierarchy of human needs’ (Figure 1.1), which suggests that until those needs which will ensure survival are met, such as for food, water, and warmth, humans are not motivated to achieve the other needs (all of which Maslow deemed to be psychological in nature) appearing further up the hierarchy.

Another explanation might be that patients do not particularly expect to experience a caring relationship with their nurses or other caregivers; they have primarily come into the health care system to gain help for their physical problems. Their immediate concerns are likely to be getting a diagnosis for their troubling symptoms, or having their pain and discomfort relieved, rather than a meaningful relationship. It may also be that patients hold stereotypical views of their carers, perhaps seeing nurses, for example, as ‘angels’, and thus they expect expressive caring to be naturally present. Therefore they do not identify it as a particular sign of caring (Kyle 1995). While it may be true that patients neither expect nor want a ‘meaningful relationship’ with their carers, it cannot be assumed that have no need of expressive caring.

As we shall see, this distinction between carers’ and patients’ perceptions and expectations of caring has implications for understanding the nature of psychological care, which is perhaps less likely to be delivered through instrumental, observable, tangible actions, and more likely to be delivered through expressive activities.

Figure 1.1 Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

The relationship between personal and professional caring

Reflection point

Think back to the last time you felt ‘cared for’ by another person. Who was that person? What exactly did he or she do to make you feel cared for? Can you describe what that experience felt like?

Caring in a lay context

We have all been ‘cared for’ or been ‘taken care of’, as babies and dependent infants. As we have grown, we will, in turn, have experienced caring for other people such as friends, partners, and family members, in an everyday or ‘lay’ context. In your reflections, you may have identified experiences such as when someone went out of their way to help you, or put you first. You may have remembered specific behaviours, such as a hug or having a cup of tea made for you. You may recall feeling valued as a person, or feeling safe, or any number of other emotions. You may have found it difficult to put into words what the experience was like, or even to recall a recent caring experience. This exercise perhaps illustrates how very diverse, uniquely experienced, and elusive the concepts of ‘care’, ‘caring’ and ‘being cared for’ really are, even in an everyday context. How much more difficult, then, to explain what we mean by care and caring as used in the specific context of professional health care?

Many authors have sought to distinguish between caring in the general sense or as practised by ‘lay’ (non-professional) carers, and professional or formalised caring. It is estimated that there are around six million lay carers in the UK, who ‘provide unpaid care by looking after an ill, frail or disabled family member, friend or partner’ (Carers UK 2007). Brechin (1999) undertook a study with lay carers of both older people with dementia and adults with intellectual disabilities. She concluded that lay care is ‘caring about’ someone within the context of a personal relationship, and that it implies an emotional commitment to the person requiring care. ‘Caring about’ is somehow different from ‘caring for’. Although this explanation is not universally accepted, it has contributed to the search for the essential ingredien...