- 104 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

With the increased use of computers, architecture has found itself in the midst of a plethora of possible uses. This book combines theoretical enquiry with practical implementation offering a unique perspective on the use of computers related to architectureal form and design. Notions of exaggeration, hybrid, kinetic, algorithmic, fold and warp are examined from different points of view: historical, mathematical, philosophical or critical. Generously illustrated, this book is a source of inspiration for students and professionals.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture GeneralChapter 1

Caricature Form

Caricature is a term used to describe an exaggeration, a skillfully stretched and intentionally deformed alteration of a familiar form. While caricature is associated with the resulting sketch and its contextual meaning, the art of caricature involves the forces of deformation and their connotative value. In its generative stage, caricature touches one of architectural design’s deepest desires: to build life into lifeless forms. In its manifold implications, caricature touches many of architecture’s most deeply embedded assumptions about its existence: the struggle of architectural form to stand out, inspire, and identify itself. Traditionally the struggle of architecture has been to express its form through its function without disturbing the balance between the two. Forms convey strong visual messages that are intrinsically associated with their formal characteristics. What makes a caricature so polemic for architects is that the modern movement has imposed a strong concern towards the dominance of form. The importance of form in architecture, as opposed to function and content, has the advantage of taking into account the idiosyncratic links of architecture to its major relative, art. The disadvantage, however, is that formalism, among Modern theorists, has connotations of being too iconolatric, superficial, and conformist. As a consequence, formalism has always been regarded suspiciously as combining the icons of historical architecture and technological development at a surface level.

Challenging these concerns, a caricature is a celebration of form at its most existential level. It provides a medium of expression that is subtle, implicit, connotative, and indirect, yet powerful, expressive, and emotional. Because of its highly connotative nature, caricature’s power lies in the value of its subliminal messages. A successfully exaggerated figure provides the means of expression that can stir emotions and attract attention. It is analogous to poetry. A caricature deformation is not simply an alteration of an existing form but rather an implicit juxtaposition of a familiar archetype. The notion of familiarity plays an important role, as it becomes the basis of comparison between the original and the deformed. As in poetry, the power of caricature lies not only in the presence of formal features but also in the subtle presence of their absence.

Caricature differs from, but is often confused with, cartoon. While cartoon implies context and action, caricature involves the exaggeration of a form and its shaping forces; it suggests personality, character, identity, distinctiveness, individuality, and connotation. In cartoon, it is the sequence of events that lead, to a result, whereas in caricature it is the figure itself that implies an emotion. In architecture, the discussion on cartoons follows the strip or cinematic model, where the multiplication and sequencing of static frames lead to a humorous situation. The problem with this model is that architecture occupies the role of the static frame through which motion progresses. In contrast, caricature is the static frame through which motion is implied.

In many fields of design, “caricaturization” is a common practice. In industrial, automotive, manufacture, and graphics design, to name but a few, the end product is intentionally exaggerated to suggest indirectly a certain visual effect. In automotive design, for example, the space of design is conceived as a deformable grid that can mimic the shape, posture, or pose of animals or human silhouettes.1 While physical form is defined in terms of mathematical surfaces, the virtual archetype of the environment in which it is designed contributes to its shape. The static Cartesian system of architecture is replaced by the dynamic design space of engineering. Forms are conceived in their totality and not as collections of constituent components.

Likewise, the forms of a dynamically conceived architecture may be shaped through deformations of virtual archetypes. Actual sculpture involves chiseling marble, modeling clay, or casting in metal, whereas virtual sculpture allows form to occupy a multiplicity of possible formations continuously within the same form. This concept of a soft form, which can be selectively deformed in design space, is radically different from the idea of a rigid archetype. The soft form is a result of an infinite continuum of possible variations. The assignment of particular variables governs its internal structure. The form in flux is possible by defining its geometry parametrically. Once conscious of the immaterial constitution of the object, once conscious of its not being marble, clay, metal or glass, but only a three-dimensional representation of reality, a topological morphology is conceivable and possible.

The term deformation is often used in a negative sense. It implies the degradation or perversion of a “healthy” figure. In architecture, deformation is a term often used to denounce a fundamental change in the structure of a form. The prefix “de-” often implies departure from a common practice and suggests challenging an established status quo. In that context, the term deformation is not a negation, but rather an affirmation. It implies an alternative way of creating form.

In virtual design space, deformation is conceived as a proportional re-distribution of points along a direction. The notions of “redistribution” and “direction” imply the existence of time as a measure of comparison. In order to conceive the change dictated by the deformation it is important still to recognize the previous state of the form, before the deformation occurred. The true value of a deformation is not in the end result but in the infinitesimal slice of time where past and present overlap within the same form.

In all of these threshold conditions of time, a superimposition of the viewer’s interpretation is put into relation such that the deformed shapes are conceived through the impression of real motion. Although form is conceived of as static when observed as discrete pictures, the viewer’s experience of form is interactive and dynamic. Deformation suggests the superimposition of invisible forces in the same way that soft clay implies the hands of a sculptor. The attributes of softness, elasticity, plasticity and flexibility imply the act of deformation.

Historically, exaggerations of the human figure, or parts of it, were used to convey political or religious messages, such as power, divinity, terror, fertility, sexuality, and so on. By implying a quantitative interpretation of form, any exaggeration in size, shape, or attribute automatically suggests a corresponding exaggeration of the signified form’s quality: the bigger something looks, the more important it is, and vice versa. Thus, the demarcation of extremes establishes a ground for comparisons.

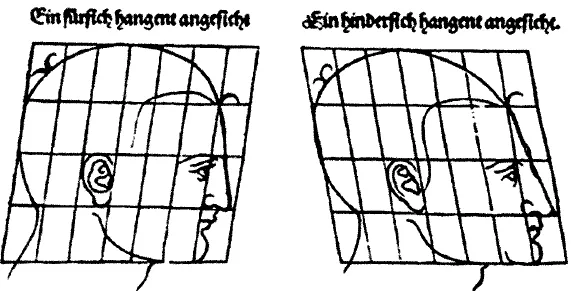

The model of quantitative exaggeration is based on the profound linear relationship between size and importance. It is also possible that exaggerations may occur in the form of proportional alterations. One of the first “caricaturists” to study the effects of proportion on the human face was Albrecht Dürer. What is remarkable about his studies is that he used a dynamic grid to investigate the relationship between face and geometry. Instead of enumerating faces as isolated events and then trying to connect them, he used geometry as the medium of investigation. By altering the proportions of the grid, Dürer was able to create various caricature faces of existing or nonexisting persons.

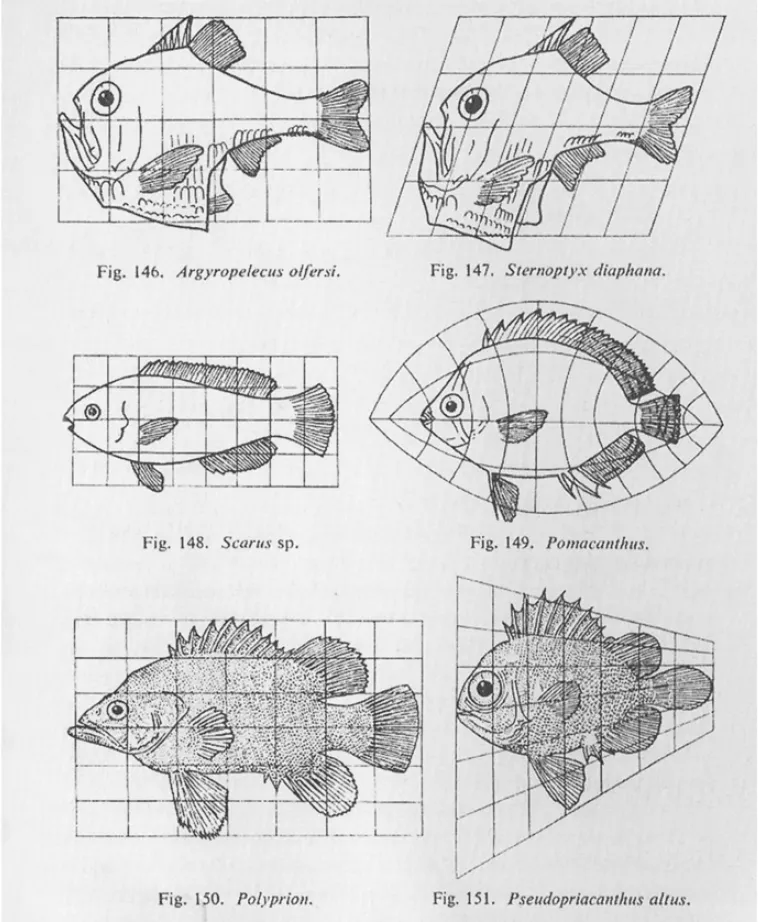

In the work of biologists we see similar studies of deformations, alteration, and unintended caricatures of animals and organisms. Even though the biologists’ intention was to find missing links or continuity in species, from a formal point of view the grids and guides used to describe the process of evolution offer a glimpse into a world of caricature. What is interesting about these studies is the use of nonlinear systems of deformation based on proportional alterations of a superimposed mesh. Curvature becomes more important than linear scaling. Under these systems, even inanimate objects, such as bones or fossils, can be seen as caricatures.2

1.1 Alterations of the proportions of geometry affect the human figure, features, and facial expression

(From Albrecht Dürer’s treatise on proportion, Les Quatres livres d’Albrecht Dürer de la proportion des parties et pourtraicts des corps humains, Arnheim, 1613)

Even though humans and animals appear relatively easy candidates to caricaturize, given their strong expressive nature, a challenge arises for inanimate objects. How can a lifeless form appear to have lifelike properties? The cartoon industry has a rich history of inanimate caricature characters. From candles that dance to cookies that hide, inanimate objects seem to be able to possess human characteristics. The strategy often is simple: attachment of a face or use of a human posture to give character. Similarly, in Disneyland’s Toontown, buildings are caricaturized by applying deformations similar to the ones used to create favorite characters: Mickey’s home, for example, has strong curves, clumsy postures, and thick frames.

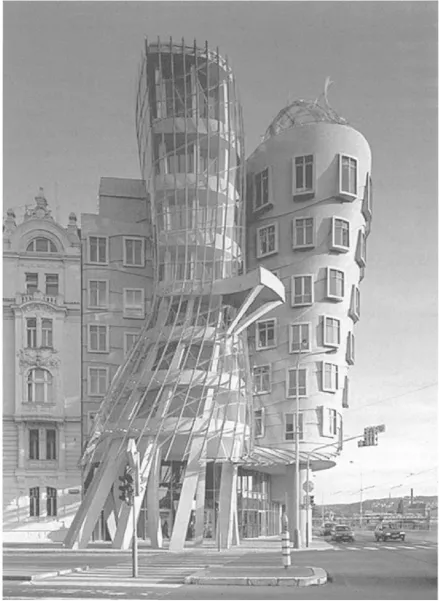

In the work of architect Antonio Gaudi, inanimate forms such as chimneys, roofs, windows, or balconies are deformed to imply an organic caricature effect. Similarly, in the work of architect Frank Gehry, curves and manifolds imply posture and personality. The body language of the towers in Prague nicknamed Fred and Ginger implies the intermingled postures of dancers Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. Resting lightly on top of slender columns, the glass tower, with its pinched waist, leans gracefully towards a proud cylindrical tower.

1.2 Geometrical manipulations of species’ evolution instances

Irony is a term used to indicate the use of a pattern to express something different from, and often opposite to, its literal meaning. It is a special juxtaposition of form and content where one expresses the opposite of the other. The power of irony, as a subliminal mechanism, is based in its contrasting yet comparative nature. In the art of caricature, irony is often used as a means of formal expression. Within all possible alterations of form, some stand out as representations of irony. Surprisingly, representation itself is a form of depiction that represents something else. In the special case that it represents the opposite of what one would expect, it becomes ironic.3

In architecture, the use of an established archetype with a symbolic content can function as a source for irony through caricature deformations. Ideally, for modern theorists, the form of a building represents its content. Throughout the history of architecture, certain forms have been associated with certain types of buildings. The deformation of a symbol or its meaning has a dramatic ironic effect. A factory, for example, has a certain organization, structure, shape, and texture that identifies its existence. Most importantly it is a symbol of the working class and as such it carries a strong connotative value. Any deformation of the form of a symbol carries strong connotative repercussions. It is that relationship, between form and content, that allows formal ironic statements to be made. In the work of the Italian architect Aldo Rossi, primitive forms with strong symbolic architectural meaning, such as chimneys, pyramid roofs, colonnades, and flags, are being used by the architect to construct buildings whose function is often the opposite of what they symbolize.4 A school with a chimney or a federal building that looks like a factory is an ironic architectural statement. In that context, the primitive Euclidean forms play the role of the formal identifier, while its function plays the role of the social identifier.

Caricature design employs formal logic in its conception and interpretation. It is based on formal relationships filtered through layers of interpretation. Specifically, deformation and exaggeration are compositional operations that affect the relationships among key elements of the caricature. The operations define the composition and the composition implies the operations. That is why regardless of race, size, or gender, any person deformed in a certain way will look cute. In reverse, cuteness is associated with certain proportions that are, in turn, the result of certain deformation operations.

In Euclidean geometry, form is conceived as the result of a system of abstract relationships. Forms represent idealized versions of conceptual patterns and not perceivable objects. The formal relationships that define primitive shapes are based on the condition of stasis, or balance of conceptual forces. Euclidean primitives describe special conditions where an equilibrium state has been obtained. A sphere is not about roundness but rather about the equal distance of points from a central point. The ellipse, which in Greek means omission, reflects a “failure” to obtain the equilateral equilibrium of a sphere.

In the world of caricature, Euclidean forms play the role of a point of reference to an archetype. The condition of equilibrium reflects certain formal quali ties that are associated with the states of initialization or termination. Stability, discreteness, and timelessness are qualities of primitive shapes, which, in turn, are associated with security, steadiness, and durability. These qualities are the basis of reference for formal deformations, as they become the measure of departure from the original state or the proximity of arrival toward the final state. Considering a verbal description, for example, of Gehry’s Fred and Ginger building, it may involve a phrase such as “a cylinder with a pinched waist that leans gracefully toward another proud cylindrical tower”. Geometrically, the corresponding formal event involves “a thin cylinder bulged inward around its center, then sheared backward and toward another thick cylinder tapered at its base and bulged at the top”.

1.3 “Toontown” in Disneyland, California

A direct way of defining new forms in Euclidean geometry is through linear or curvilinear transformations of primitives. Equal scaling, for example, of all three-dimensional components, creates similar forms that differ in size. Size, as we pointed out earlier, is associated with quantity. Caricature design uses the measure of size, either relative or absolute, as a means of exaggeration. Differential scaling, on the other hand, allows a selective exaggeration of size. The variation of the proportions of a form can produce a variety of interpretations. Slim, slender shapes suggest grace and elegance, whereas womb-like round shapes suggest warmth or comfort. A form tilted forward may suggest aggression or curiosity, whereas the same shape tilted backward may suggest fear or concern. The interrelationship between primitive forms and primitive emotions is of great importance in caricature design. It involves a dialectic definition of emotion which assumes that certain forms are alive, while our experience of them may be the opposite. Alive becomes the condition of form acted on by emotion, while lifeless becomes the condition of form resting in equilibrium. Both positions assume that emotion is something which can be added or subtracted from form.

1.4 Towers in Prague, nicknamed Fred and Ginger, imply the intermingled postures of dancers Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers

Euclidean transformations, such as movement, rotation, scaling, or reflection, incubate within a closed, isolated and hermetic environment, while forms, under the influence of transformations, may change in shape, size, direction, or orientation-no parts are added or subtracted from the scene. It is the forces of deformation that change, not the integrity of the objects. In contrast, Boolean operations are constructive or deconstructive tools that allow new elements to be added to a scene and others to be removed. Addition suggests superimposition, whereas subtraction implies the presence of absence. For caricature design, Boolean operations allow the notions of absence or presence to be implied, which, in turn, allow time to be imprinted on form. “Before” and “after” are simply the results of a set operation where the parent’s ghosts are still present in the shapes of its children. A mold, for example, is the negative of a positive form, neither of which would exist without the other. Set operations are not part of the Euclidean world per se. Contrary to the idealized immaterial existence of forms in Euclidean geometry, Boolean operations incorporate the behavior of matter. In that sense, their apprehension is connected to our empirical experience of matter and its properties. In the work of architect Richard Meyer, for exampl...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Foreword

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Caricature Form

- Chapter 2 Hybrid Form

- Chapter 3 Kinetic Form

- Chapter 4 (Un)Folding Form

- Chapter 5 Warped Eye

- Chapter 6 Algorithmic Form

- Epi(dia)logue

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Expressive Form by Kostas Terzidis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.