This is a test

- 230 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hitler and Nazi Germany

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Hitler and Nazi Germany provides a concise introduction to Hitler's rise to power and Nazi domestic and foreign policies through to the end of the Second World War. Combining narrative, the views of different historians, interpretation and a selection of sources, this book provides a concise introduction and study aid for students.

This second edition has been extensively revised and expanded and includes new chapters on the Nazi regime, the SS and Gestapo, and the Second World War. Expanded background narratives provide a solid understanding of the period and the analyses and sources have been updated throughout to help students engage with recent historiography and form their own interpretation of events.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Hitler and Nazi Germany by Stephen J. Lee in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia del mundo. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE RISE OF NAZISM

BACKGROUND

The Nazi movement originated in Munich as the German Workers’ Party (DAP), established immediately after the end of the First World War. Hitler, previously an impoverished Austrian artist who had served in the German army, joined in November 1919. He was placed in charge of the Party’s propaganda and was largely responsible for drafting the 25 Point Programme in 1920 and for renaming the movement the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP). The following year he supplanted Anton Drexler as party leader and extended National Socialist (Nazi) activities into the media, with the acquisition of the Munich Observer (Münchener Beobachter), and into paramilitary activism with the formation of the Sturmabteilung (SA).

The early conception of Nazism was revolutionary. In 1923 Hitler made a bid for power in Munich, clearly encouraged by the success of Mussolini’s March on Rome the previous year. The attempt ended in failure; Hitler was tried for treason and sentenced to a term of imprisonment in Landsberg Castle. While he was out of circulation the NSDAP fell into disarray and had to be refounded on his release. Hitler now proceeded to revitalise the party and to alter his whole strategy for achieving power. Instead of coming to power by revolution, he now proposed to achieve his objective by legal means and then to introduce the revolution from above. Between 1925 and 1929 he succeeded in winning over the northern contingents of the NSDAP under Gregor Strasser and Goebbels, and in establishing his authority through a series of local party officials known as Gauleiter.

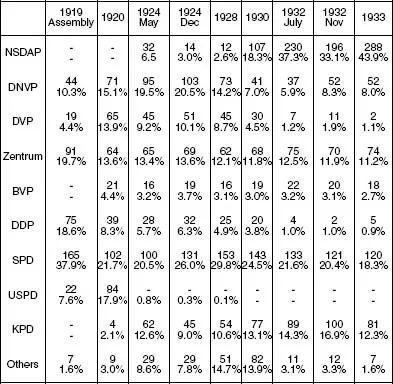

The actual results of these developments are contentious. On the one hand, the NSDAP performed very badly in the Reichstag (or elected chamber) elections, dropping seats between 1924 and 1928. On the other hand, there is evidence of a major upheaval below the surface within the middle classes which made them more receptive to the appeal of Nazism from 1928 onwards, a process which was accelerated by the Great Depression. The working class, too, became more fragmented and a substantial portion was detached from its normal political allegiance. The electoral impact of such changes was startling. The NSDAP won 107 seats in 1930 and were easily the largest party in the elections of July and November 1932.

This chapter focuses on the meaning of Nazism – in terms of its ideas and what it came to mean to those who joined the NSDAP or came eventually to vote for it. Analysis 1 considers the origins and growth of Nazism as an ideology, the influences upon it and where it fits into the modern world. It also considers whether it was part of a more generic phenomenon – the crisis of modernism – or whether it grew in the unique environment of Germany’s own past. Above all, was Nazism entirely the creation of Hitler?

Analysis 2 deals with the growing support in Germany for Nazism. It starts with the changes made after the Munich Putsch within the NSDAP in terms of strategy, organisation and propaganda; it then looks at the way in which these changes attracted support within every sector in German society to make the NSDAP the largest and most diverse of the parties in the Reichstag.

The increase in popular support for the Nazis did not inevitably mean their rise to power: after all, Hitler never held a majority in the Reichstag and he lost the Presidential election to Hindenburg in 1932. Nevertheless, the way in which others viewed the surge of Nazism after 1931 meant that Hitler was eventually appointed Chancellor as the result of political intrigue. This element of his rise is covered separately in Chapter 2.

ANALYSIS 1: WHAT WAS ‘NATIONAL SOCIALISM’ AND WHY DID IT BECOME ESTABLISHED IN GERMANY?

The main components of National Socialism can be found in three main sources: the 25 Point Programme, Mein Kampf and the Zweites Buch. Further policies and ideas were contained in Hitler’s Speeches and the Tischgespräche, the latter based on records of his table conversations.

The Programme, formulated in 1920, contained principles which could be seen as both nationalist and socialist. The former predominated, demanding ‘the union of all Germans in a Greater Germany’ (Article 1); the ‘revocation of the peace treaties of Versailles and Saint-Germain’ (Article 2); the acquisition of ‘land and territory to feed our people and settle our surplus population’ (Article 3); the replacement of Roman Law by German Law (Article 19); the formation of a people’s army (Article 22); and the establishment of ‘a strong central state power’ (Article 25). The nationalist component was given further emphasis by a strong racial slant. Hence, Jews were to be excluded from German nationhood (Article 4); all ‘non-German immigration must be prevented’ (Article 8); and non-Germans should be excluded from any influence within the national media (Article 23). The socialist element was apparent mainly in the emphasis on ‘physical or mental work’ (Article 10); the ‘abolition of incomes unearned by work’ (Article 11); the ‘confiscation of war profits’ (Article 12); extensive nationalisation of businesses (Article 13); ‘profit-sharing in large industrial enterprises’ (Article 14); the extension of old-age insurance (Article 15); and land reform (Article 17).1 These clauses, however, reflect the radicalism of Hitler’s ideas less than Mein Kampf. Written between 1924 and 1926, this focused more on racial rather than economic explanations for major historical trends. Here he argued that ‘The adulteration of the blood and racial deterioration conditioned thereby are the only causes that account for the decline of ancient civilizations; for it is never by war that nations are ruined, but by the loss of their powers of resistance, which are exclusively a characteristic of pure racial blood’.2 Anti-Semitism was conjoined with anti-Marxism which, in turn, made Soviet Russia Germany’s main external enemy. This meant that ‘the end of Jewish rule in Russia will also be the end of Russia as a state’.3 Through future expansion, Germany would achieve its rightful Lebensraum at the expense of the ‘inferior’ races of the east, a theme he revisited in 1928 in his Zweites Buch, largely concerned with foreign policy, and more randomly in his Tischgespräche.

The consensus among historians is that National Socialism was irrational and disordered as an ideology. It was certainly looser and more eclectic than Communism, which was based on the tighter format of dialectical materialism. The 25-Point Programme was the closest the movement ever came to a list of objectives – but the name at the bottom of this document was that of Drexler, not Hitler. The latter felt no fundamental commitment to all of its provisions, preferring to articulate his ill-defined aims separately and with a much heavier emphasis on race. According to Kershaw, ‘Hitler’s ideology has been seen less as a “programme” consistently implemented than as a loose framework for action which only gradually stumbled into the shape of realistic objectives’.4

Where did these ideas come from? Hitler was certainly affected in his early years in Vienna by the far-right and anti-Semitic influences of Karl Lueger, leader of the Christian Social Party and Georg von Schönerer, a prominent member of the Pan-German movement in Austria: Hitler was particularly influenced by the latter’s propaganda for the union of all Germans within a Greater Germany. Mein Kampf also reveals a partially digested and incompletely understood version of a range of nineteenth-century philosophers including Hegel and Nietzsche. Reflecting a general consensus on this, Bullock argues that ‘Every one of the elements in his world-view is easily identified in nineteenth-century and turn-of-the-century writers, but no-one had previously put them together in quite the same way’.5 There is, however, disagreement as to why Hitler’s own synthesis should have led so readily to the conquest of Germany by National Socialism. Three broad routes of transmission have been suggested. The first is that Germany’s own past made it particularly susceptible, the second that the spread of National Socialism was the most extreme manifestation of a general European phenomenon, and the third that Hitler himself exerted a unique impact unequalled by anyone else.

Some historians have emphasised that Germany was especially receptive to National Socialism because of its own unique history or ‘special path’ (Sonderweg). Three separate strands can be identified. One is the failure of Germany’s middle classes to capture the political initiative in 1848 and 1849; this ‘lost revolution’ meant that Germany was eventually united by force and came under the authoritarian rule of the Kaiserreich (1871-1918). The fracturing of German liberalism remained apparent even during the era of the Weimar Republic (1919-33), as National Socialism was able to slip through the defences of parliamentary democracy and establish at least a degree of continuity between the Third Reich and the Second. A.J.P. Taylor took the argument further. The whole process, he maintained, involved the surrender of Germany to authority. ‘During the preceding eighty years the Germans had sacrificed to the Reich all their liberties; they demanded as reward the enslavement of others. No German recognized the Czechs and Poles as equals. Therefore every German desired the achievement that only total war could give.’6 Other historians have seen in this more than a simple abandonment of collective judgement. Shirer, for example, argued the case for an underlying continuity between National Socialism and Germany’s cultural past, which produced a ‘spiritual break with the west’.7 In this sense, Mein Kampf offered ‘a continuation of German history’.8

But the Sonderweg approach is seen by many as too restrictive as an explanation for the emergence of National Socialism. An alternative interpretation is that Nazism was the most radical part of a process which was not confined to Germany, but which affected other parts of Europe. It is, for example, a long-established Marxist view that Nazism was one manifestation of a general crisis of capitalism; East German historians, in particular, maintained that Hitler was above all the tool of big business. As a variant of fascism, Nazism represented a late phase in the development of capitalism, in which a declining political structure has to be replaced by something more robust if monopoly capitalism itself is to survive. According to the East German historian, Eichholtz, ‘Fascism represents no separate socioeconomic formation, no new phase within the capitalist social order; its economic foundations and trends are monopoly-capitalistic, imperialistic’.9 Hence Hitler had little independent input: he was merely part of a larger process. This analysis is, however, deeply flawed. It is based on a preconceived formula for historical change which was used to provide ideological justification for the political system that replaced Nazism in East Germany. As such, it fails to explain why some countries remained democracies in spite of experiencing similar problems. Capitalism, in other words, was equally capable of assuming democratic forms.

Non-Marxist historians also acknowledge an economic influence but place this within a broader context of national and international influences. Particular sections of the German population were vulnerable for economic reasons which had their roots in the nineteenth century: the middle classes experienced a crisis of industrialisation which made them susceptible to radical ideas. These, too, had a long history, in the form of pan-Germanism and anti-Semitism, and in the quest for Lebensraum (‘living space’). During the Second Reich (1871-1918) these ideas had been confined to the fringe but, within the crisis of Germany’s experience between the Wars, they became the focal point. None of them were new, but Nazism was particularly effective – in an eclectic sense – in combining ‘snippets of ideas and dogmas of salvation’, which could be used as ‘a deliberate simplification of political world views’.10 Many – although not all – non-Marxists also believe that Nazism was part of the fascist mainstream. The roots were a widespread disillusionment with modernism and rationalism and the emphasis on a curiously-twisted form of romanticism. Fascism also emphasised the profound threat of communist and socialist parties, while, at the same time, drawing upon a number of socialist ideas which had been modified to appeal to the middle classes. Fascism everywhere was militaristic and expansionist, focusing upon the revival of centralism within the state and future conquest outside it. All fascist parties depended upon the cult of a father-figure and developed mass movements to energise the masses with enthusiasm and commitment. According to Broszat, therefore, National Socialism was rooted in a combination of ‘the general European crisis’ and ‘Germany’s national history and its peculiar divergence from the West’.11

For many historians nothing comes close to rivalling the personal influence of Hitler himself in the development of Nazism. Some even suggest that Nazism had become crystallised in his mind even before he came to power in Germany. Trevor-Roper, for example, believes that the formative period for this was the First World War, and that by 1923 it had taken the ‘systematic form’ which was later ‘deducible from his Table Talk’.12 In all this, Hitler’s ‘personal power was in fact so undisputed that he rode to the end above the chaos he had created, and concealed its true nature’.13 Bullock, too, accentuates the personal influence of the Führer:

More important is the fact that, having created his own version, the essential elements of which were set out in Mein Kampf and completed by the time he wrote his Zweites Buch in 1928, Hitler never altered it. There is a recognizable continuity between the ideas he expressed in the 1920s, his table talk in the 1940s, and the political testament which he dictated in the bunker just before he committed suicide in April 1945.14

All three approaches have to be used to explain the rise of Nazism in Germany, although their exact proportion will always be controversial. There are, however, certain leads. Fascism without Mussolini is just about imaginable, and historians have even drawn a distinction between ‘Mussolinianism’ and fascism. But no one has seriously suggested separating ‘Hitlerism’ from Nazism: an integral component of Nazism was the ‘Führer principle’ (Führerprinzip). It is true that the cult of leadership is to be found in all fascist movements, but it was of particular importance in the Nazi context since Hitler’s ideas were crucial in defining the eclectic nature of Nazism. Above all, Hitler provided Nazism with a unique vision of racial purity and anti-Semitism which were initially absent in Fascist Italy. In this respect, as in others, the generic label of German fascism hardly seems appropriate. On the other hand, we should not write out longer-term approaches. The popularity of Hitler is impossible to explain without the existence of a strong degree of receptivity within Germany – and this could well be set in a wider European context. There was much in Hitler which was ludicrous: it was converted into a compelling form of radicalism because it worked upon the needs of the population at the time.

Figure 1 Reichstag election results 1919-33

Questions

- Was ‘National Socialism’ the right name for Hitler’s movement?

- Were the Nazis ‘fascist’?

ANALYSIS 2: HOW AND WHY DID THE NAZIS ATTRACT INCREASED SUPPORT BETWEEN THE EARLY 1920S AND 1932?

Between 1920 and 1932 the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) was transformed from a fringe völkisch group with a very limited appeal to the largest political party in Germany. The process was slow at first, the ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Outline chronology

- Series preface

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Acknowledgements

- 1 The Rise of Nazism

- 2 The Achievement and Consolidation of Power 1933-4

- 3 The Nazi Dictatorship

- 4 Indoctrination and Propaganda

- 5 The SS and Gestapo

- 6 Support, Opposition and Resistance

- 7 The Nazi Economy

- 8 Outside the Volksgemeinschaft

- 9 Foreign Policy

- 10 Germany at War

- Glossary

- Notes

- Select bibliography

- Index