- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ancient Meteorology

About this book

The first book of its kind in English, Ancient Meteorology discusses Greek and Roman approaches and attitudes to this broad discipline, which in classical antiquity included not only 'weather', but occurrences such as earthquakes and comets that today would be regarded as geological, astronomical or seismological.

The range and diversity of this literature highlights the question of scholarly authority in antiquity and illustrates how writers responded to the meteorological information presented by their literary predecessors.

Ancient Meteorology will be a valuable reference tool for classicists and those with an interest in the history of science.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

GeschichteSubtopic

Altertum1: ANCIENT METEOROLOGY IN GREECE AND ROME: AN INTRODUCTION

Today, for many of us, the word ‘meteorology’ conjures up images of the evening news and the weather forecasts offered by television ‘meteorologists’. Given the current debates regarding global warming and climate change, the term ‘meteorology’ points to a science concerned with controversial and difficult-to-prove hypotheses. For many people, meteorology appears to be a speculative subject, in which predictions are very often not borne out. Indeed, current chaos theorists emphasize the difficulty (if not impossibility) of making accurate weather predictions. Nevertheless, or perhaps because of a shared sense of frustration, the weather is always a ‘safe’ subject for conversation, for we assume that everyone is interested in it. Indeed, a certain preoccupation with it is regarded in some regions and occupations as completely normal.

We often have the impression that meteorology is primarily concerned with weather prediction, yet it is not only concerned with forecasting, but also with the explanation of weather phenomena. (Indeed, some would argue that it is difficult or impossible to predict without understanding the causes of weather.) Today, understanding the causes of weather and climate is regarded as necessary, in order to cope with phenomena like El Niño and to prevent global warming. And while the relationship between the ability to explain and to predict natural phenomena is not always straightforward, we tend to regard the ability to predict as a hallmark of modern science.

This book focuses on ancient Greek and Roman approaches to the prediction of weather and the explanation of the causes of meteorological phenomena. In ancient Greece and Rome, the study of meteorology covered a broader range of phenomena than is usual today, and was of interest to many, including farmers, poets, philosophers and physicians. The modern term ‘meteorology’ comes from the ancient Greek word meteōrologia, which refers to the study of the ‘meteōra’. But the answer to the question ‘what does the term meteōra cover for the ancients?’ is not straightforward, for not all the authors considered here agree. Some, for example Plato, used related terms to refer to thinking about ‘lofty’ things, but it is not entirely clear what these ‘lofty’ things were.1 We might expect that ancient meteorology would focus on things high in the atmosphere. When we look at the ancient Greek and Roman texts on meteorology, we discover discussions about ‘lofty’ things which today would be regarded as astronomical phenomena, such as comets and the Milky Way. However, earthquakes and other phenomena that would today be regarded as geological and seismological were also treated in ancient texts on meteorology. And, as we would expect from our modern term, much of ancient meteorology too was concerned with weather.

Given the predominance of farming in ancient society, it is not surprising that Greek and Roman authors wrote a great deal about the weather. Furthermore, the movement and transport of agricultural stock and manufactured products were vital in the ancient world. Those who had to organize such movements were, of necessity, much concerned with weather. But the study of ancient meteorology was not simply a practical matter. Many ancient authors who wrote on the subject were aiming to address important questions about the nature of the world and how we understand it, questions about whether or not the cosmos is a unity, and what sort of explanations of the cosmos (and its parts) are possible.

While the main aim of this study is to provide an overview of ancient Greek and Roman approaches to the prediction and explanation of meteorological phenomena, there are several ‘sub-plots’ underlying the work. One is a concern with the forms in which these approaches have been set down, described and disseminated. Because of the diverse character of the ancient texts, I devote some attention to questions of format and genre. Sometimes, because of our own implicit expectations regarding modern scientific communication, we are surprised by the range and diversity of the forms of communication of scientific ideas and methods in other periods and cultures.

Poetry plays an important role as a central genre for sharing meteorological information, and not only in antiquity. The use of poetry as a way of communicating scientific ideas may be surprising to modern sensibilities. Several major Greek and Latin poets (including Hesiod, Aratus and Lucretius) composed poems that included, in some instances, detailed meteorological material; some of these poems (including that of Aratus) were verse treatments of prose treatises. And prose authors of learned and technical treatises incorporated quotations from and allusions to these poems. In other words, authors of didactic prose treatises considered the poets to be authoritative sources of information on meteorological matters.

Questions relating to format and genre can also be revealing with respect to the relationship of authors to their predecessors. In many cases our primary sources are fragmentary, incomplete, or lost, and our understanding of ancient meteorology is derived from ancient authors reporting the ideas, methods, or observations of others. This book is based on an attempt to reconstruct, through ancient accounts, a brief (and not complete) history of ancient meteorology. Of course, those ancient authors who preserved and reported the work of others did so for their own purposes, which did not include the production, in the early twenty-first century, of a history of ancient meteorology. Recognizing this, while I have tried to query the purpose behind each author’s approach and ‘motives’, I realize the limitations of trying to discover and understand any author’s ‘agenda’.

By paying attention to the issues raised by the genre and format of ancient works on meteorology and also to questions regarding the value, usefulness and reliability of information contained in the works of others, I intend to signal that these ancient works display interesting tensions regarding the status of authorities and the use of knowledge derived from them. These tensions are deeply embedded in the cultures and values of the Greco-Roman world and contribute to the rich complexity of ancient projects to predict and explain meteorological phenomena.

Insights into ancient notions about the weather are found in the earliest extant ancient Greek works, the Homeric and Hesiodic poems, which include many references to meteorological phenomena. Of course, the primary purpose of the ancient poets was not to explain and predict weather phenomena, but the poems do give both incidental and deliberate indications of archaic Greek ideas about the weather, and the use of such knowledge. The audiences of the poems were probably not particularly interested in meteorology, but the descriptions of weather phenomena would have carried familiar meaning. Furthermore, the poems of Homer and Hesiod serve as points of reference in later discussions of meteorology. Both poets are echoed and quoted by numerous later authors on meteorology. Hesiod, in particular, is mentioned in relation to prediction; references to Homer sometimes feature in explanations of weather.2

The authorship and dating of the epic poems have been debated since antiquity (beginning at least in Alexandria), but there is now general consensus that the Iliad and the Odyssey, both attributed to Homer, were composed in the second half of the eighth century BCE. The Iliad is thought to be older than the Odyssey; the first is dated to about 750 BCE and the second to about 725 BCE. Little is known about the poet known as Homer and it is a question whether the same author composed both poems. Interestingly, the description of weather phenomena has led some to locate the author of the Iliad on the eastern side of the Aegean; the poet’s description of the winds suggests familiarity with regions east of Thrace.3 The Theogony and the Works and Days are both generally ascribed to Hesiod. From the fifth century BCE onwards, scholars disputed which of the two epic poets, Homer or Hesiod, was the older. A date for Hesiod of around 700 BCE is now accepted.

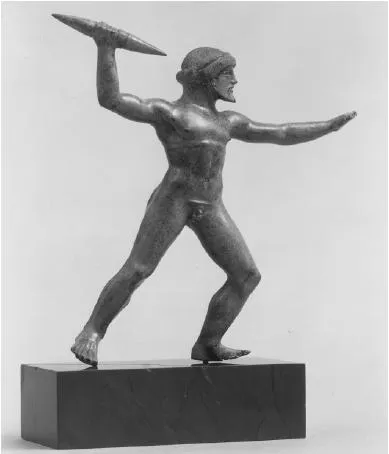

Figure 1.1 Bronze statuette of Zeus with thunderbolt, c. 470 BCE, found at Dodona (ancient oracular temple and sanctuary of Zeus).

Source: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin-Preußischer Kulturbesitz Antikensammlung.

In the Homeric and Hesiodic poems, meteorological phenomena are often linked to the activities of gods. Many meteorological phenomena are personifications or epiphanies of gods, or are sent directly by Zeus. In the Iliad and the Odyssey, Zeus, sometimes referred to as ‘cloud-gatherer’ (Od. 5.21; Il. 1.511), is often responsible for meteorological events.4 Rain comes from Zeus; at Il. 12.25 Zeus rains continually. He produces thunder (Od. 14.305) and hurls bolts of lightning (Il. 8.134; Od. 12.415). Zeus is described as carrying lightning in his hand (Il. 13.242); he causes storms (Od. 9.67; see also Il. 15.379; Il. 16.385f.); and places rainbows in the clouds as a portent for humans (Il. 11.27–8). But other divinities can also produce meteorological phenomena; for example, together, Hera and Athene cause thunder (Il. 11.45). Winds may come indirectly from Zeus (Il. 2: 144–6, where Euros and Notos raise the waves, springing from the clouds of father Zeus); winds can also be controlled by various gods. In the Odyssey (Od. 5.382–5) Athene is able to control the wind:

But now Athene, daughter of Zeus, planned what was to follow.

She fastened down the courses of all the rest of the stormwinds, and told them all to go to sleep now and to give over, but stirred a hastening North Wind, and broke down the seas …5

The goddess Kalypso sent a wind to carry Odysseus across the sea (Od. 5.167). Poseidon, often described as ‘earth-shaker’ (Od. 1.74, 5.423), also pulled together clouds and let loose a storm of winds (Od. 5.291–6). As the ‘earth-shaker’, Poseidon has control over not only seismological but also meteorological phenomena. At one point in the Odyssey (Od. 10.19ff.), we learn that Zeus put Aiolos, a mortal, in charge of a bag containing all the winds. Aiolos stowed the bag carefully, tied up with a silver string, letting out only the West Wind to blow ships safely on their course. But greedy men were curious about the contents of the bag. Believing it might contain silver and gold, they opened it, releasing all the winds, resulting in a storm which swept them away. Control of the weather has great symbolic value in the Homeric poems.

The Hesiodic Theogony presents a lengthy and complicated genealogy of the gods, in which a mythological account of meteorological phenomena is crucially embedded. Zeus, son of Kronos and Rhea, is the storm-king, the cloud-gatherer. Following various exploits, with the help of the Hundred-Handers he drives the Titans from heaven:

And now Zeus no longer held back his strength.

His lungs seethed with anger and he revealed

All his power. He charged from the sky, hurtling

Down from Olympos in a flurry of lightning,

Hurling thunderbolts one after another, right on target,

From his massive hand, a whirlwind of holy flame.6

Following this, Gaia (Earth), pregnant by Tartarus, gives birth to Typhoeus, and we then get a good deal of weather and winds; Typhoeus is the source of winds which cause shipwrecks and destruction.7 The Homeric and Hesiodic gods play crucial roles in causing and controlling meteorological phenomena.

Some would discount mythological accounts as being of no interest from a ‘scientific’ standpoint. But the whole question of what is ‘scientific’ is not agreed upon by historians and philosophers of science, least of all for the ancient period. Some argue that the only ancient texts worthy of the appellation ‘scientific’ are mathematical works, yet most historians of science, as well as historians of philosophy, would agree that the ancient writings on natural philosophy are properly studied as part of the history of science. Whether or not that makes those writings ‘scientific’ is another matter. The relationship between traditional mythology and ancient philosophy is complicated, as the ancients themselves acknowledged.

Myth was regarded by many ancient philosophers, including Plato, as an acceptable form of description and explanation. Both Plato (Cratylus 402b; Theaetetus 152e, 180c–d) and Aristotle (Metaphysics 983b27f.) suggested, perhaps jokingly, that Homer and Hesiod were the fathers of ancient philosophy. W.K.C. Guthrie noted that ‘Plato was fond of calling Homer the ancestor of certain philosophical theories because he spoke of Oceanus and Tethys, gods of water, as parents of the gods and of all creatures’.8 While such pronouncements may have been made lightly, there may also have been an element of seriousness. Within some definitions of mythology, the accounts of the traditional gods and their meteorological activities may be understood, quite reasonably, as a form of explanation. There was an ancient tradition of regarding the earliest poets as intellectuals; standing at the fountainheads of tradition, they helped shape intellectual agendas. While ancient philosophers were by no means unanimous in their views of the early poets, the variety of reactions to them indicates a perceived need to engage with their accounts.9

Certainly, many meteorological phenomena, including storms, lightning and thunder, are potentially dangerous and frightening. Many practical activities (including farming and seafaring) are, to some extent, determined and circumscribed by meteorological events. The use of mythology to explain this group of phenomena and the reliance on signs and omens to predict their occurrence are an important part of the fabric of many cultures, including several in antiquity. The desire to account for and to predict weather phenomena is shown in the literature that survives. In addition to early mythological accounts and omen literature, there is a large body of literature that spans the ancient period and is concerned with explanation and prediction of meteorological events. This literature, produced by some of the most influential writers of antiquity, falls into two distinct traditions: one philosophical and largely explanatory, the other for the most part predictive and linked to observation (and recording) of phenomena, including astronomical events and animal behaviour.

While it is always difficult to determine the origin of an idea or methodology, the importance of the Hesiodic poems and their influence on later ancient authors writing about meteorology were clearly significant. The Works and Days stands at the beginning of a special tradition of astrometeorological texts, which correlate astronomical phenomena with the seasons and with weather events. To a large extent, the final section of the Works and Days may be regarded as an early farmers’ almanac.10 In the Homeric poems, there is a sense of an annual cycle of recurrent seasons (‘the year had gone full circle and come back with the seasons returning’, Od. 10.467f., 11.294–5; Il. 2.550). Several seasons are mentioned: winter, spring, summer, late summer/early autumn.11 These seasons are marked in various ways: in some, particular sorts of weather are characteristic. The Iliad 16.384–5 describes the late summer/early autumn (o̓πώϱη) as a time of violent rain and flooding. Winter (χειμών) is a time of unceasing rain (Il. 3.4) and stormy weather (Od. 4. 566, 14.522). Spring (έ̓αϱ, Il. 6.148) is windy, and also the time of the nightingale’s song (Od. 19.519). The Homeric poems give some slight evidence of a relation between astronomical phenomena and agricultural seasons: late summer/early autumn (oπwϱη) is referred to as the time of the star known as Dog-of-Orion (Il. 22.29), which is also a time of harvest (Od. 11.192) and fever (Il. 22.30–1). However, the link between an astronomically based calendar and agricultural activity is not well developed in the Homeric poems and certainly not to the extent that is evident in Hesiod’s Works and Days.12

The ancient practice of using the risings and settings of bright stars to mark out the seasons and to predict weather phenomena was based on ideas that the motions of the heavens are related to terrestrial events, particularly weather.13 Astrometeorological parapēgmata (lists of star phases and associated weather predictions) and the astrological literature, including Ptolemy’s (second century CE) Tetrabiblos, are examples of the astronomical tradition of weather prediction, which will be examined in the next chapter. This tradition survived through late antiquity and was developed further in the medieval period, in both the Arabic and Latin traditions, and continued well into the early modern period.

Weather prediction was useful not only for farmers, but also for physicians. For example, the author of the Hippocratic medical treatise on Airs, Waters, Places states at the outset that physicians must be familiar with the differences between the seasons, so as to know what changes to expect in the weather and to predict the effects on the health of themselves and their patients.14

In addition to the ancient mythological accounts and the traditions of weather prediction, there are other writings which attest to interest in talking about the weather. Herodotus devoted a lengthy section of his Histories (part of Book 2) to a description of the Egyptian weather and climate, as well as other meteorological topics. Aristophanes, in the play The Clouds (331ff.), humorously criticized the new learning of Socrates and other ‘sophists’ who, he suggested, were ‘always talking about clouds and things’.

Natural philosophers, from the Presocratics through the Hellenistic period, discussed the causes and offered explanations of weather phenomena. Sadly, only fragments (in some cases lengthy) and the titles of Presocratic philosophical texts survive. Fortunately, Aristotle’s lengthy treatise, the Meteorology, provides information not only on his...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- ANCIENT METEOROLOGY

- SCIENCES OF ANTIQUITY

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- A NOTE ON THE SPELLING OF GREEK NAMES AND TERMS

- ABBREVIATIONS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- 1: ANCIENT METEOROLOGY IN GREECE AND ROME: AN INTRODUCTION

- 2: PREDICTION AND THE ROLE OF TRADITION: ALMANACS AND SIGNS, PARAPEĒGMATA AND POEMS

- 3: EXPLAINING DIFFICULT PHENOMENA

- 4: METEOROLOGY AS A MEANS TO AN END: PHILOSOPHERS AND POETS

- 5: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC APPROACH

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Ancient Meteorology by Liba Taub in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Altertum. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.