This is a test

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Religious Traditions in Modern South Asia

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book offers a contemporary approach to the study of religion in modern South Asia. It explores the development of religious ideas and practices in the region, giving students a clear and critical understanding of social, political and historical context.

- Part One takes a fresh look at some familiar themes in the study of religion, such as deity, authoritative texts, myth, worship, teacher traditions and caste, and helps students understand diverse ways of approaching these themes.

- Part Two focuses on some of the key ways in which Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam and Sikhism in South Asia have been shaped in the modern period. Overall the book considers the impact of gender, politics, and the way religion itself is variously understood.

The chapters contain a compelling range of primary source materials and a series of geographical and historical 'snapshots' to orientate readers to South Asia. Valuable features for students include images, task boxes, discussion points, suggestions for further reading, a timeline and glossary of terms.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Religious Traditions in Modern South Asia by Jacqueline Suthren Hirst,John Zavos in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introducing South Asia, Re-introducing ‘Religion’

‘South Asia’ is the name given to a region that includes the modern nation-states of Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and the Maldives. Together, these countries constitute an enormous area of the world, home to a population of roughly 1.6 billion people, about 23 per cent of humanity. It is an area that has, for centuries, been strategically significant in global geo-political terms, the site of many empires, and a critical global trade arena since at least the first millennium BCE. In the contemporary era, it is distinctive as a region where you will find, in the Republic of India, one of the fastest-growing and most powerful economies in the world. At the same time, it is one of the world’s poorest regions; World Bank figures indicate that in 2005 more than 40 per cent of the population across the region lived on less than $1.25 per day (World Bank 2011: 66). It also hosts two of the world’s nuclear powers (India and Pakistan).

South Asia is, then, a region of great significance in the contemporary world. Our objective in this book is to provide some insights into one important feature of the region: its religious traditions. It is a commonplace to say that South Asia is a region of great religious diversity (see Box 1.1). In this book we want to investigate what this well-worn phrase actually means, by exploring the development of its religious traditions in a range of social and political contexts.

Box 1.1 Enumerating Religion in South Asia?

- Bangladesh (total population 154 million): 89.7 per cent Muslim; 9.2 per cent Hindu; 1.1 per cent other.

- Bhutan (700,000): ‘Two thirds to three quarters’ Buddhist; ‘approximately one quarter’ Hindu; ‘less than one percent’ Christian and non-religious.

- India (1.15 billion): 80.5 per cent Hindu; 13.4 per cent Muslim; 2.3 percent Christian; 1.9 per cent Sikh; ‘Groups that constitute less than 1.1 percent of the population include Buddhists, Jains, Parsis (Zoroastrians), Jews and Baha’is’.

- Maldives (298,000): ‘The vast majority of the Muslim population practices Sunni Islam’.

- Nepal (30 million): ‘According to the government, Hindus constitute 80 percent of the population, Buddhists 9 percent, Muslims 4 percent, and Christians and others 1 to 3 percent. Members of minority religious groups believe their numbers were significantly undercounted.’

- Pakistan (174 million): ‘Approximately 95 percent of the population is Muslim. Groups composing 5 percent of the population or less include Hindus, Christians, Parsis/Zoroastrians, Baha’is, Sikhs, Buddhists, Ahmadis, and others.’

- Sri Lanka (20.1 million): ‘Approximately 70 percent of the population is Buddhist, 15 percent Hindu, 8 percent Christian, and 7 percent Muslim.’

These figures and quotations are drawn from the US Department of State’s (2010) ‘Annual Report to Congress on International Religious Freedom’. As you can see, the ability of the report to provide accurate figures is variable, as in some nation-states the exact religious identity of citizens or subjects has not been established. Where accurate figures are provided, they are generally based on 2001 census statistics gathered by the respective nation-states.

Even where census data has been gathered, the diversity that is hidden by labels such as ‘Hindu’ and ‘Muslim’ means that the language of accuracy and exactness can be misleading. As we shall see in this book, the way that religious identity is actually lived out can contradict the apparent order and stability that such figures seek to represent.

In the broadest sense, these contexts are configured by the region itself. Its seven independent nation-states define South Asia geographically by their position on or adjacent to the Indian subcontinent. South Asia has also been defined by its historical link to the British empire, dominant in this region during the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries. On this view, we should include Burma (Myanmar) within South Asia, as it formed part of the administrative unit known as British India. We could, however, also exclude Sri Lanka, which was administered separately during the colonial period. Alternatively, if we included modern nation-states that have cultural continuities with an earlier Indian empire, the Mughal empire, we might look to the area of Persian influence and include modern Afghanistan and even Iran in our subject matter. Certainly Afghanistan has, in more recent years, been increasingly drawn into the region, as indicated by its membership since 2007 of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC). What these points demonstrate is that South Asia, rather than being a fixed entity, is a conceptual construct that changes according to the contexts in which it is located.1

As with the region, so with its religious traditions! They are also, we argue, constructed differently in different contexts. Under such circumstances, attempting comprehensive coverage of these traditions would appear a dubious enterprise; it is not one we will attempt in this book. Our intention, rather, is to supply you, the reader, with a range of perspectives and diverse examples and so, we hope, provide a critical and thought-provoking method for studying religious traditions in modern South Asia.

You may already have noted the play on ‘tradition(s)’ and ‘modernity’ in our title. This partly reflects our desire to trace the continuities as well as the changes that have shaped understandings of religion in the modern era. It is also a challenge, an initial encouragement to reflect on such categories. Religion is often presented as the traditional antithesis to the inexorable secularity of modernity. Our hope is that this book will question such neat assumptions, demonstrating, rather, that the categories through which we understand the world around us are continually and mutually constructed. ‘Tradition’ and ‘modernity’ are two such categories. ‘Religion’ is another.

So one of the tasks we have set ourselves in this first chapter is to ‘reintroduce’ religion within such a critical framework, as a prerequisite for our exploration of South Asian religious traditions.2 Before turning to this task, however, we want to provide some perspectives on the region itself, to situate it in space and time. As with our broader project in this book, we do not attempt to provide a sense of totality; rather, we give a series of specific ‘snapshots’, brief views of a vast, multi-dimensional (and indeed limitless) terrain.

Situating South Asia 1: Landscapes of Diversity

Fly then from the Himalaya mountains in the north down the west coast of India to the southern town of Kochi (Cochin) in the state of Kerala. Engaged in trade with the Mediterranean, Arabia and the Persian Gulf from Roman times onwards, and later used as a staging post for trade to China, this coast of southwest India has enjoyed cosmopolitan status for centuries. A swift look around the small district of Mattancheri in Kochi confirms this history and its impact upon religious traditions in South Asia. Just north of Jew Town Road stands the Paradesi Synagogue, founded in 1538 and rebuilt in the eighteenth century – the synagogue for ‘foreigner’ traders or White Jews as they were known. By contrast, the so-called Black Jews, long-time Indian Jews whose ancestors married Jewish traders from perhaps as early as the sixth century CE, were deemed in the Paradesi Synagogue to have lower status. This alerts us that issues of social status cross-cut religious allegiance here as elsewhere in the world. Since 1948, the majority of Cochin Jews have emigrated to the modern state of Israel, having lost their political privileges when the Princely State of Cochin became part of Kerala in 1947 (Gerstenfeld 2005). They do not show by religion on the 2001 census. In the past, though, local Hindu rulers acted as patrons to Jews (as well as Christians and others), giving financial support and guaranteeing their right to practise their own traditions. The ability of different groups to ‘slot’ into local social relations has been an important factor in shaping religious traditions in South Asia.

Right next door to the synagogue is the Dutch Palace, first built by the Portuguese in 1555 for the Hindu Raja of Cochin. Now a museum, within its walls is the still-functioning Pazhayannur Bhagavati temple, to the Goddess of the rulers of Cochin, alerting us to the idea that state and religion may be closely connected. Another wall of the synagogue is shared with a temple to Krishna, a different deity. Later in the book, we shall ask about the relations between such temples and deities. Part of the answer may be to do with the places from which different groups have migrated. To the west and north of the synagogue is an area now largely inhabited by people from Gujarat and Kutch in northwest India, who have settled here again largely as the result of trade links. During the Navratri nine nights festival to the Goddess in September/October, the Dariyasthan temple is full of Gujaratis dancing the dandiya, a lively stick dance that they have brought with them and taught their children. They are probably mainly Lohana, belonging to a particular trading caste, temples (and deities) being sometimes linked with caste groups as well as regional leanings. This is the case with churches too. Following the road from there north, you will come across a Gujarati school, reminding us of the importance of retaining one’s own language* when surrounded by neighbours who speak a different one, here, Malayalam. Perhaps 400 metres along the same road, you will see the Cutchi Memon Hanafi Mosque, its name aligning its community with an area spanning the India/Pakistan border (Kutch), a particular group of Muslims (Memons) and one of the four main branches of Islamic law (the Hanafi). They will share a language (if not the exact dialect) with those who dance at the Gujarati temples nearby, as well as with worshippers at the big Jain temple lying between the mosque and the Gujarati school. This Bhagwan Shri Dharmanath Jain temple, built in 1904, represents another migration from Gujarat, going back perhaps to the early nineteenth century. Now its website proclaims proudly its place in the pluralistic microcosm of Mattancheri, ‘Mini-India’. We have started to see why.

The Ernakulam district in which Mattancheri lies is also diverse. It had as many Christians as Hindus according to the 2001 census. Although some churches in this area date back to the influence of Portuguese Catholics from the sixteenth century, there were Christian communities in this part of India from as early as the second century, as we know from Roman sources (even if there is no hard evidence for the story that St Thomas, one of Jesus’ twelve disciples, himself came to south India). The history of Christianity in India therefore predates that in, say, Britain by at least a couple of centuries, that in America by over a millennium. When we look at religious traditions in modern South Asia, we need to keep this history of diversity and change in mind.

Now fly over a thousand miles northeast. You will come to a sprawling megacity. Not Kolkata (Calcutta), in West Bengal, the colonial capital of British India until 1911, and fifth largest city in the world (13,217,000 population in the 2001 census), but Dhaka, the capital of modern Bangladesh, East Bengal, with a current population of over 10 million. In this great ‘City of Mosques’, straddling the banks of the River Baraganga, just over 10 per cent of its population are Hindus. Sometimes, major Muslim and Hindu festivals coincide, leading to extended celebrations in the city.3 In 2007, for example, Eid ul-Fitr fell in October. Each Eid, between 7:30 and 10:00 A.M., Dhaka’s 360 specified Eidgahs (Eid grounds) and mosques are packed with Muslims saying their Eid prayers, with special provision made for women. Dressed in colourful new clothes, people visit family and friends, and share Eid delicacies and sweets. In 2007, in the days that followed, Hindu neighbours celebrated Durga Puja, the biggest festival of the Bengali Hindu year. Visit Shakari Bazar and women are walking in brightly coloured saris just like those of their Muslim counterparts at Eid, twenty temples packed into the sixty metres or so of this old Hindu street with buildings three or four storeys high going back deep from the narrow road. Pandals (pavilions) for the Goddess Durga are set up, neighbours visited, sweets enjoyed. A Muslim writer, Fakrul Alam, remembers Eids and Durga Pujas in the 1960s of his childhood, when Hindu and Muslim friends and families would exchange sweets and share one another’s festivities in the Ramakrishna Mission area of Dhaka. Now his young nephew does not go inside puja pandals. ‘We aren’t supposed to’, he says (Alam 2007). But the government takes measures to ensure both festivals pass off peacefully, stressing that Bangladesh protects the religious rights of all.

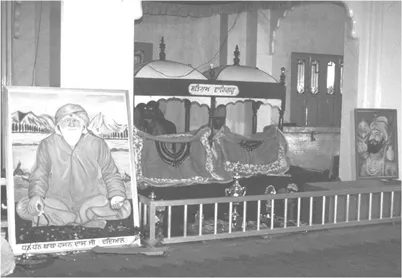

Northwest a further thousand miles lies the village of Dadyal, Hoshiarpur District, Punjab, India (Figure 1.1). Affected, like Bengal, by the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, the villages in this area are now Sikh and Hindu. Muslims fled over the border into Pakistani Punjab.4 Yet on a Thursday evening in this area, women, men and children from the villages will gather at Sufi shrines to offer their respects to the pir or holy man in the place where he was united in ‘marriage’ with Allah at death. Then they will stay for the langar (meal), sitting in rows on the ground, sharing food offered to all who come. Just outside Dadyal village itself is the shrine of Baba Hasan Das. He bears a Muslim name (Hasan), is worshipped by Sikhs and Hindus, offers cures to any who come to the place under a tree where he used to meditate, and now has his picture in the gurdwara, alongside the Guru Granth Sahib (Figure 1.2). Nearby, the village temple to the Hindu deity Shiva lists donations from both Hindus and Sikhs, many from the UK, especially from Leicester, where a blogger notes a langar for Baba Hasan Das is held in one of the Sikh gurdwaras (Randip-Singh 2007).

Figure 1.1 Dadyal village across the tank. Reproduced courtesy of Roger Ballard.

Figure 1.2 Inside the gurdwara: Baba Hasan Das (left of our picture) and Guru Gobind Singh (right) with Guru Granth Sahib and Dasam Granth on twin palkhis. Reproduced courtesy of Roger Ballard.

Our final port of call, a mere hop of around 300 miles southwest, is in the heart of the ‘cow-belt’, the area of Uttar Pradesh in north India where Hindu identity is particularly strongly emphasized. Mathura, on the river Yamuna, is renowned as the birthplace of Lord Krishna. In the holy area of Vraj (Braj), where Krishna played with the gopis (the girls who looked after the cows), he is believed to play still with those who have eyes to see. Yet in this area, different local traditions have jostled since the time of Gautama Buddha, who is supposed to have commented that Mathura was overrun with devotees of the Yakki (Yaksha) cult, semi-divine beings associated with the earth and trees. In Mahaban, for example, a village of largely low-caste people and Muslims, the cult of Jakhaiya is run by Sanadhya brahmins, but preserves some very non-brahmin Yaksha rituals, involving a rooster and a pig that in the past would have been sacrificed. Now the pig’s blood is offered to the earth from a cut made in its ear.

Local stories also bear testimony to contestation and negotiation between particular groups of brahmins who moved into the area from the sixteenth century onwards, when Krishna devotion really started to flourish here. Different sites and forms of devotion were legitimated from the mouth of Shree Nathji himself (Krishna), devotees of the Vallabha Pushtimarg tradition and the Bengali Chaitanya tradition telling the same story very differently (Sanford 2002). As in the other places we have visited, you can find in Mathura an imposing mosque among the many temples and wayside shrines. Yet alongside manifestations of Hinduism and Islam, the paths of ancient ritual, multiple traditions and renegotiated pilgrimage routes run deep.

Situating South Asia 2: Snapshots of History

We now turn from space to an exploration of South Asia in time. In the course of this book, we will be looking at particular historical moments in some depth, especially in Part II. Here, we offer a series of snapshots of South Asian history. These help us to map our landscapes of diversity further. For maps, of course, exist in time as well as space. Consider, for instance, the two maps shown in Figures 1.3 and 1.4. The latter is a contemporary political map of the region, showing the independent nation-states of South Asia (although not their contested boundaries). The former is a map of the region in 1795, showing British territories and others. As you can see, the largest identifiable presence at this time was the ‘Mahratta Confederacy’, a network of federated states that during the eighteenth century had superseded the Mughal empire as the principal political authority in large areas of central India. The change over this period of just over 200 years is demonstrably dramatic. A map of India from a period in between – say, 1860 – would again show a dramatically different picture.

Figure 1.3 South Asia in the eighteenth century. Originally published in Charles Joppen (ed.) (1907) A Historical Atlas of India for the Use of High Schools, Colleges and Private Students, London: Longmans, Green and Co.

Figure 1.4 South...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of boxes

- Preface

- A note on orthography (how words are written)

- 1. Introducing South Asia, re-introducing ‘religion’

- Part I: Exploring landscapes of diversity

- Part II: Shaping modern religious traditions

- Modern South Asia: a timeline

- Glossary

- Notes

- References

- Index