- 348 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Perspectives on Cognitive Dissonance

About this book

Published in 1976, Perspectives on Cognitive Dissonance is a valuable contribution to the field of Social Psychology.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction to the Theory

Imagine a fearful person who cannot find an adequate cause for his fear. His knowledge, on the one hand, that he is fearful is quite inconsistent with his knowledge, on the other, that there is nothing to fear. Such an inconsistency in knowledge, according to Festinger (1957), gives rise to a psychological state which he called “cognitive dissonance.” Cognitive dissonance was defined as a motivational state that impells the individual to attempt to reduce and eliminate it. Because dissonance arises from inconsistent knowledge, it can be reduced by decreasing or eliminating the inconsistency. Thus, according to Festinger’s analysis, a fearful person who could find nothing to fear is motivated by cognitive dissonance either to reduce his fear or to find some fear-provoking event. Accomplishment of either of these possibilities eliminates the state of cognitive dissonance.

While the example of a fearful person who has nothing to fear contains the central idea of dissonance theory, it omits those aspects of Festinger’s (1957) theoretical statement that distinguished it from other theories of cognitive balance (e.g., Heider, 1958; Newcomb, 1953). Most notably, the original statement of dissonance theory included propositions about the resistance-to-change of cognitions and about the proportion of cognitions that are dissonant, both of which allowed powerful and innovative analyses of psychological situations. It was the inclusion of these latter propositions that not only distinguished dissonance theory from other theories of cognitive balance, but also made dissonance theory a fertile source of research.

The theory we shall present here is an evolved version of Festinger’s (1957) original statement. The only significant change from the original has to do with the concept of personal responsibility, to be described later.

SPELLING OUT THE THEORY

Cognitions, Consonance, Dissonance, and Importance

Any bit of knowledge that a person has about himself or the environment is a “cognition,” or “cognitive element.” Cognitions about the self would include such components as knowledge of one’s weight, awareness of hunger, the memory of a previous visit at the dentist’s office, and the intention to go to the bank tomorrow. Cognitions about the environment would perhaps include knowledge of the distance between London and Paris, knowing which candidate for political office is a Democrat, perceiving that grass is green, recalling that one’s car is in need of repair, and expecting the sun to rise tomorrow. Cognitions may be very specific bits of information or they may be general concepts and relations, and they may be quite firm and clear or they may be vague.

The relationship between two cognitive elements is consonant if one implies the other in some psychological sense. Psychological implication can arise from cultural mores, pressure to be logical, behavioral commitment, past experience, and so on. What is meant by implication is that having cognition A implies having cognition B. Knowing that steak is a tasty food is consonant with knowing that one is eating steak. Similarly, a person’s knowledge that he has voted for John Smith to be mayor is consonant with his belief that Smith has the qualities of a good mayor. The detection of psychological implication is frequently possible by measurement of what else a person expects when he holds a given cognition.

If having cognition A implies having cognition B, a dissonant relationship exists when the person has cognitions A and the obverse or opposite of B. If, for example, a person knows that he voted for candidate A and he also believes that candidate A is unworthy of public office, he has two cognitions that are in a dissonant relationship. Whenever a person has two or more cognitions that are dissonant with regard to each other, he experiences cognitive dissonance, a motivational tension.

Many cognitions that a person has will be neither consonant nor dissonant— that is, these cognitions will have nothing to do with one another. Such cognitions are said to be irrelevant.

When a person holds two cognitions that are in a dissonant relationship, the amount of dissonance he experiences is a direct function of how important those cognitions are to him. For example, a person about to fight a guerilla war who also has knowledge of the personal dangers of such wars possesses two dissonant cognitive elements, and the relatively great importance of these elements would give rise to a considerable amount of cognitive dissonance. In contrast, the knowledge that it is raining coupled with the dissonant knowledge of having forgotten the umbrella would create less dissonance because these cognitive elements are not as important as those in the life-or-death guerilla warfare example.

Our description of dissonance theory thus far depicts the idea as little more than a notion about cognitive conflict or cognitive imbalance. And aside from the effect of importance, we have mentioned no way to calculate different degrees of dissonance. The factor to be introduced next, “resistance to change of cognitions,” has a direct bearing on both of these issues. Through an analysis of the malleability, or “fixedness” of relevant cognitions it becomes possible to speak about degrees of dissonance, and we also are enabled to derive a distinct class of phenomena that are nowhere implied in other statements of cognitive consistency.

In the above examples used to illustrate the arousal of cognitive dissonance no mention was made of how dissonance would actually be reduced. Given the definition of a dissonant relationship, all that could be said about dissonance reduction is that there will be some attempt to eliminate the dissonant relationship by changing one element or the other in order to render the two either consonant or irrelevant. In addition to making possible statements about the degree of dissonance, the concept of resistance to change allows statements about the directions to be taken by the dissonance-reducing individual.

Resistance to Change of Cognitive Elements

Cognitions—elements of knowledge—vary in the extent to which they are resistant to change. A person’s perception of the greenness of grass is highly resistant to change; for people with normal vision it would be exceedingly difficult to see grass as being any color other than green. In contrast, judgments about which college basketball team is best, about the pallatibility of steak au poivre, or about the amount of money that should go into the nation’s defense budget, may not be completely firm and in many cases can be quite unstable. Compared to the perception of green in grass, the latter cognitions have relatively little resistance to change.

In general, there are two distinguishable sources to resistance to change. The first is the clarity of the “reality” represented by the cognition. What normally are referred to as “facts”—that is, that grass is green—are aspects of the world that give rise to clear and firm cognitions. At the other end of this dimension are events that are highly ambiguous—what the quality of life will be like a century from now, or how many grains of sand there are on the outer banks of North Carolina. Cognitions about the latter kind of event will, of course, have relatively low resistance to change.

The second source of resistance to change comes from the difficulty of changing the event that is cognized. Historical events, for example, cannot be changed and cognitions concerning them will therefore be highly resistant to change. Contemporaneous events, on the other hand, will sometimes be easy to change and when they are, the cognitions representing them have low resistance to change. If a person finds, for example, that his air conditioner is making too much noise to allow sleep, the air conditioner can be turned off.

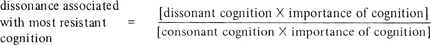

The Magnitude of Dissonance

When there are both consonant and dissonant relationships among the elements of a set of relevant cognitions, the calculation of the magnitude of dissonance is carried out using the most resistant cognition as a focal point, or point of orientation. The magnitude of dissonance with regard to the most resistant element is a direct function of the proportion of relevant elements that is dissonant with it. In other words, given the most highly resistant cognition, the magnitude of dissonance is increased with regard to that cognition as the number of dissonant cognitions increases; the magnitude of dissonance with regard to that cognition decreases as the number of consonant cognitions increases. This formulation can be schematically represented as follows:

Note that each consonant or dissonant cognition is weighted for its importance to the individual.

The schematic representation helps to make clear an interesting aspect of the theory, namely, that with the number and importance of dissonant cognitions held constant, the magnitude of dissonance decreases as the number or importance of consonant cognitions increases. Let us suppose, for example, that a person has voted for John Smith to be mayor despite also believing that Smith is not very bright, and let us assume that the cognition about voting is the more resistant element. The magnitude of dissonance that our voter experiences from this dissonant relationship is an inverse function of the number of cognitions that are consonant with the knowledge that he voted for Smith. If he voted for Smith because he believes Smith to be honest and he also believes that Smith endorses the right side on all important election issues, then these consonant cognitions in addition to the dissonant one will add up to only negligible dissonance. However, if the only reason he had for supporting Smith was his belief in Smith’s honesty, then the consonant cognitions do not clearly outweigh the dissonant (that Smith is stupid), and the magnitude of dissonance experienced is relatively great.

Dissonance Reduction

As the schematic representation indicates, dissonance can be reduced in several ways. Dissonant cognitions can be eliminated, or their importance can be reduced. Consonant cognitions can be added, or the importance of preexistent consonant cognitions can be increased. In the above example of voting for Smith as mayor, the voter could reduce dissonance by convincing himself that Smith was really not so dumb, or by thinking that brightness is not a necessary characteristic for being a good mayor. In addition, or instead, he could magnify the importance of having an honest mayor, or he could find additional reasons for thinking that Smith would be a good mayor.

This delineation of ways in which dissonance can be reduced does not indicate what a person who is experiencing dissonance will actually do. First of all, the theory does not assert that a person will be successful in reducing dissonance, but rather that the existence of dissonance will motivate a person to attempt to reduce it. Second, the way in which a person attempts dissonance reduction will depend in part on the resistance to change of the relevant cognitions. In general, we may expect that attempts to reduce dissonance, and successful dissonance reduction, will involve cognitive operations on those cognitions that are least resistant to change. Opinions (i.e., cognitions about somewhat ambiguous events) and cognitions about easily changed aspects of reality will tend to be the locus of dissonance reduction efforts.

While the cognition of a recent behavior or behavioral commitment, such as a decision, is usually assumed to be the element most resistant to change, this cognition will occasionally be less resistant to change than one or more of the cognitions with which it is dissonant. Consider, for example, a case in which a person has bought a sports car and has found that those characteristics of the car about which he had predecisional misgivings indeed make driving the car unpleasant. If the individual is unable to convince himself that he really likes to drive the car, then his dissonance will persist and indeed will be salient every time the car is driven. Under these conditions, dissonance reduction may more easily be accomplished by changing the cognition about the behavior. While it would be difficult to deny that the car had been purchased, it may not be so difficult to change the reality—to come to believe that buying it was a mistake, and to sell it. In this case, the resistance to change of the behavioral cognitive element is less than that of the cognitions with which it is dissonant, and dissonance reduction is accomplished by changing the behavioral element. The way dissonance is reduced here also illustrates an important theoretical point, namely, that dissonance reduction is organized around the cognition that is most resistant to change, whether or not that cognition has its basis in a behavioral commitment.

Many of the analyses to come later involve cognitive dissonance between a recently performed behavior and an attitude. For example, a person first holds a particular political belief, and then is asked to take a contrary position in some overt fashion. It may be naive to say that one cognition (recent behavior) is firmly rooted in behavior, while the other (prior attitude) is not. If for example the attitude is a political belief, there is every likelihood that some sort of belief-consistent action has been taken previously. Perhaps the person has voted consistently with his beliefs in earlier elections, or he may have campaigned on behalf of candidates representing these beliefs. This being the case, are we not dealing with two opposing cognitions that should both be highly resistant to change? And if so, which cognition is the stronger? Around which cognition will dissonance be reduced?

Since it is generally true, in experimentation, that attitudes do in fact shift in the direction of the more recent commitment, it becomes necessary to make an extratheoretical assumption having to do with the recency of behaviorally based cognitions. In general, if two cognitions are in opposition, both of which represent behaviors or other events that are in close touch with the constraints of reality, it is the more recently acquired cognition that possesses the higher resistance to change. There are at least two plausible reasons for this:

1. Taking an overt position at variance with an earlier one is a form of conversion. It may generally be true that a conversion is difficult to reconvert. There are barriers of having to admit to hypocrisy, indecisiveness, and uncertainty; and

2. The recent behavior is bound to be more salient in the individual’s consciousness. If previous behaviors are relatively out of mind, they provide less basis for a highly resistant-to-change cognitive element.

One additional point must be made in regard to behavioral commitment. Explorations in Cognitive Dissonance (Brehm & Cohen, 1962) emphasized behavioral commitment not only as an anchor around which dissonance is reduced, but also as a condition possibly necessary for the arousal of cognitive dissonance. Subsequently, Festinger (1964) and his associates reaffirmed the importance of commitment in the dissonance reduction process. They held that dissonance reduction processes ensue only when a commitment implies consequences that are dissonant with it. However, they did not say whether or not commitment was a necessary condition for the arousal of dissonance.

As the present emphasis on resistance to change implies, we find Festinger’s (1957) original statement of the theory to be superior to the more restrictive views. We believe that the notion of resistance to change not only incorporates the important aspect of behavioral commitment, but it also guides the researcher in thinking about the resistance of other relevant cognitions. In our above discussion of the role of resistance to change we have tried to show that a careful analysis of resistance must be made for all relevant cognitions in order to know around which cognition dissonance will be reduced, and in order to specify which of the logically possible ways dissonance is likely to be reduced.

Foreseeability and the Broader Concept of Responsibility

In addition to emphasizing the role of commitment in the arousal and reduction of dissonance, Brehm and Cohen (1962) raised questions about the capability of unforeseen consequences to arouse dissonance. On the basis of evidence then available, they theorized that prior choice and commitment were sufficient conditions for subsequent unforeseen (negative) events to arouse dissonance. They supposed that if a person freely committed himself to a course of action, unforeseen negative consequences of that action would result in dissonance arousal and normal dissonance reduction processes. As will be seen in Chapter 4, subsequent research has failed to support their reasoning.

Under what conditions do events subsequent to a behavioral commitment affect the magnitude of dissonance? Imagine, for example, that a person has bought a house and is becoming familiar with the consequences of that purchase. He might discover that the roof leaks, that taxes on the house are high, and that water running through the pipes is excessively noisy. Would these discoveries arouse dissonance? Suppose also that after the purchase was m...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- A Special Dedication

- Preface

- 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE THEORY

- 2. COMMITMENT

- 3. CHOICE

- 4. FORESEEABILITY AND RESPONSIBILITY

- 5. EVIDENCE ON FUNDAMENTAL PROPOSITIONS

- 6. ENERGIZING EFFECTS OF COGNITIVE DISSONANCE

- 7. AWARENESS OF INCONSISTENT COGNITIONS

- 8. REGRET AND OTHER SEQUENTIAL PROCESSES

- 9. MODES OF RESPONSE TO DISSONANCE

- 10. MOTIVATIONAL EFFECTS OF DISSONANCE

- 11. RESISTANCE TO EXTINCTION AND RELATED EFFECTS

- 12. SELECTIVE EXPOSURE

- 13. INTERPERSONAL PROCESSES

- 14. INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES

- 15. RELATED THEORETICAL DEVELOPMENTS

- 16. ALTERNATIVE EXPLANATIONS OF DISSONANCE PHENOMENA

- 17. APPLICATIONS

- 18. PERSPECTIVES

- REFERENCES

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Perspectives on Cognitive Dissonance by R. A. Wicklund,J. W. Brehm in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Social Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.