- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Project Planning, and Control

About this book

Project management is widely used in the construction industry and is central to planning and controlling time, costs and resources. This book enables readers to perform more effectively, to understand project planning and control procedures and to gain an insight into the associated skills. Numerous case examples from diverse industries and exercises support and illustrate important concepts. The result is a new perspective for project managers: planning can be shown to be a systems synthesis or an inverse problem, which provides a way to reach a satisfactory solution, avoiding the time-consuming or impractical search for the optimal solution.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture GeneralPart I

Conventional treatment from a systems perspective

Chapter 1

Introduction

Background

Many people are aware of the humorous paradoxical sign:

It also reflects a common saying, but can you plan any way other than ahead? In a like vein, people also refer in a redundant fashion to ‘future plans’, or if a project is not going well, it is said to ‘lag behind’ schedule.

Popular adages of planning

There are a number of adages and popular quotations involving planning:

In all matters, success depends on preparation. Without preparation, there will always be failure. (Confucius)

Action without planning is the cause of every failure.

Mediocrity is so easy to achieve, there is no point in planning for it.

If you fail to plan, you plan to fail.

If you don’t know where you are going, you will end up somewhere else. (L. Peter)

If you don’t know where you are going, any road will take you there.

The nicest thing about not planning is that failure comes as a complete surprise, rather than being preceded by a period of worry and depression.

4Ps Poor planning = poor performance.

6Ps Prior preparation and planning prevents poor performance.

6Ps Prior preparation prevents poor performance – probably.

Even if you do nothing, it should be done on time.

Plan the work, and work the plan.

If you plan to fail and you do, then you have been successful.

Real life is what happens when you make other plans.

The stability of a plan tends to vary inversely with its extension.

Planning also is mentioned in children’s fables. For example, one of Aesop’s fables gives the story of the ant and the grasshopper, where the ant is industrious collecting food over summer while the grasshopper plays, only for winter to come and the grasshopper goes hungry, leading to the conclusion that ‘it is best to prepare today for the needs of tomorrow.’ Aesop’s fable of the cat and the fox, where the cat knows one trick to escape the dogs and uses it, while the fox knows many tricks but cannot decide which to use and gets caught by the dogs, concludes that ‘one good plan that works is better than a many doubtful ones.’

Two noticeable things emerge from these adages and fables, and other publications on planning:

- Everyone says that there is a need for planning, and a need for genuine effort to be put into planning.

- Everybody has a different idea of what planning is.

Therein lies the source of most of the troubles preventing the advancement of the understanding of planning. To discuss these in a project context, it is first necessary to take a few steps backwards, and clarify some thinking. The first step relates to the distinction between a project and its end-product.

Project versus end-product

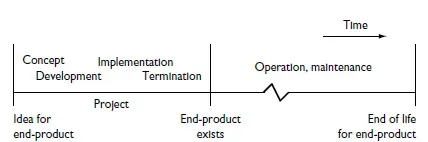

A project will commonly come about because of an identified need or want for some product, facility, asset, service and so on. This end-product is achieved through a project (Figure 1.1).

This distinction sometimes causes people confusion and many people are not aware of the distinction, or of the need to make a distinction. For example, people sometimes refer to a building as a project. It is not. The processes that go together to materialise the building are the project. The building is the end-product. (It is acknowledged that the definition of a project is sufficiently flexible to include the operation and maintenance phase of a product within what is called the project. However, this is not the issue here.)

There will be objectives and constraints relating to the end-product, and objectives and constraints relating to the project. (The plural terms objectives and constraints are generally used in this book even though the singular forms may be applicable in some situations; the exception is where the singular is deliberately intended.) The former influences what the end-product will look like and how it functions. The latter influences the way of getting to the end-product. The term ‘objective’ here is used in a correct systems synthesis sense, not as used loosely by lay people (Carmichael, 2004).

The objectives and constraints are derived from the value system of the project/end-product owner. They lead to establishing the scope, and planning practices.

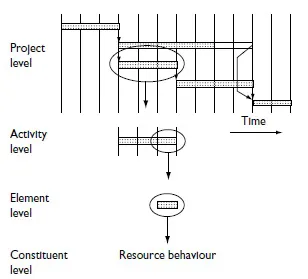

Later chapters develop a hierarchy of objectives and constraints – at project, activity, element and constituent levels. A project is composed of activities. An activity is composed of elements. Elements are composed of constituents (Figure 1.2).

Planning and design

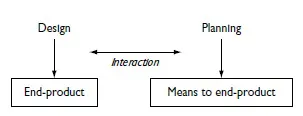

Following the distinction between an end-product and the means to the end-product, design and planning functions are seen as parallel and fundamental undertakings on projects. Broadly on a project, Figure 1.3 applies.

Figure 1.1 Project and end-product timeline.

Figure 1.2 Hierarchical levels in a project.

Figure 1.3 Fundamental project undertakings.

Both the planning and design problems are shown later to be inverse (synthesis) systems problems, although popular practice is to solve these in an iterative analysis fashion.

It is interesting to note that in nearly every project management text, there is a section on planning, and invariably the text authors feel obliged to convince the reader that there is a need for planning and of the benefits of planning, and to justify the pages allocated to planning. The same holds for courses given on planning. This indicates the immaturity of project management as a discipline and as practised. By comparison, design texts and design courses do not have to convince readers and practitioners of the need for design; it is accepted as fundamental in order to get to the end-product. Why then is not the parallel project task of planning accepted as fundamental, and let the discussion get straight on to the best way to do it?

Also of interest to note is that no owner would let a person, who has no design education, design something for them. Owners are very discerning when it comes to design. Yet anyone can get away with calling him/herself a planner without any planning credentials, and undertake planning for that same ‘discerning’ owner. Yet design and planning are both fundamental project tasks on which the project outcome equally depends. It would be nice to think the reason for this was that the owner has to live with the visual impact and functionality of the end-product, but can soon forget about the cost and duration impact of getting to the end-product. But the real reason appears to be the different maturity levels of design and planning, or more appropriately the immaturity level of planning compared to the maturity of design. It may also be that planning is an order of magnitude more difficult than design, yet it is practised by people with specialist knowledge in the inverse ratio. People have incompatible standards and expectations when it comes to design and planning work.

Another form of undesirable imbalance can be observed in some project managers and in some project management publications which take the view that activity scheduling is project management; if you have a computer package that does scheduling, then you have all that is needed to manage a project.

The false belief in the need for planning

Everyone says that there is a need for planning, and a need for genuine effort to be put into planning; the latter is acceptable (it is not unreasonable to expect that effort put into planning improves the chance of project success) but the former implies that no one recognises planning as a fundamental project task. Since planning is a fundamental project task, talk of need for planning is off the mark, as is the question ‘why plan?’ posed in books. Planning is carried out (to varying degrees of sophistication) on every project whether people realise it or not. Without planning, a project doesn’t proceed. Perhaps when people talk of a need for planning, they are talking about structured planning, as opposed to ad hoc planning, rather than talking of the no-planning versus some-planning scenario. But it is more likely that people don’t understand the place of planning.

Whether people are involved with projects or not, everyone carries out planning in some form covering the tasks that go to make up their daily lives. This applies to their home roles, social pastimes, commuting between home and wor...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- About the Author

- Preface

- Notation

- Part I: Conventional Treatment from a Systems Perspective

- Part II: Synthesis Treatment

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Project Planning, and Control by David G. Carmichael in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.