![]()

| | The life cycles of relationships | I |

![]()

| | Young adult relationships | 1 |

The interdisciplinary scientific study of couple relationships

Half a century ago scientific study of love and marriage was rare. But today many social and biological disciplines have turned their attention to couples and produced a rich variety of description, theory, and research. The varieties of relationships across time and space are studied by Anthropologists and Historians, as well as Cross-Cultural Psychologists living all around the world. The biological bases of relationships have been explored by biological psychologists and through comparative research on animals, or Ethology. In the recent past, the largest body of research and writing focused primarily on couples originated in the disciplines of Sociology, Family Therapy, and Psychology (Berscheid & Peplau, 1983).

Sociology has focused on social interaction and on the social institutions of marriage and the family. Family Therapy grew out of psychologists’ and psychiatrists’ efforts to improve the treatment of distressed marriages and families by directly observing what goes on and by devising new theories that go beyond individual psychology. Psychology contributed indirectly at first, through studying human nature, the dysfunctions of individuals, and the motivations of people in relationships. Now these three social sciences have spread out into more disciplines, including Social Psychology of Close Relationships, Family Studies, and Communications, all of which study couples as well. Still beyond this interdisciplinary field now known as Personal Relationships, cognitive neuroscience is beginning to add new knowledge about the brains of women and men that will cast light on some of the perplexing problems that occur when they interact. And finally, a new superdiscipline called Sociobiology has arisen that seeks to combine the findings of all biological and social sciences with the upgraded theories of evolution, especially in the areas of gender relating, mating, parenting, and emotions (see Chapters 9 and 13). Psychologists’ contribution is called Evolutionary Psychology (Buss, 1994). We have a rich and growing source of knowledge in the emerging science of personal relationships.

A developmental perspective

Stage models

In order to better understand what goes on in premarital couple relationships, we will divide their life cycle into stages and focus on specific processes which develop and change in the stages. Viewing relationships in this way can help us understand why we experience a glance one way at one point and another way later on. And it helps us focus on what attitudes and skills might be appropriate at different points in our relationships.

This developmental stage organization has its limitations. For the concepts of processes and stages overlap, and there are few clear cut boundaries between stages. If we generalize about the sequence of events in a “typical” relationship, there will be many exceptions to the rules. But if we distinguish several different paths of relationship development, we may exhaust the reader’s tolerance for complexity without getting much closer to an individual relationship as it is actually lived. Therefore we will describe a model of relationship development which is an extension of what has been used before.

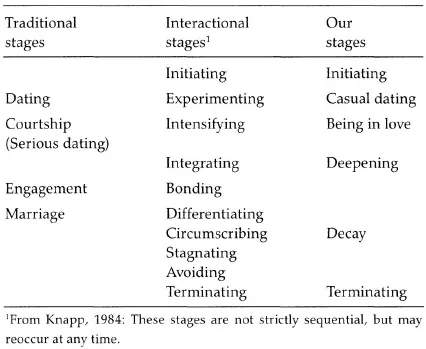

At first American writers divided relationships into four stages: dating, courtship, engagement, and marriage. Dating was viewed as “casual,” with little intention to proceed towards marriage. Courtship, or more recently serious dating, began as soon as love was declared or intentions toward the future were hatched. The sequencing of engagement and marriage was clear. But the sexual revolution in the sixties led to a decline in the rituals of courtship and the replacement of many engagements and marriages by the alternative of living together. Meanwhile social scientists were devising other criteria for making sense out of what happens between romantic partners.

Social psychologists developed the Stimulus-Value-Role (SVR) theory to cover three main aspects of choosing a future mate, and then theorized that these considerations would play major roles in three successive stages of premarital relationship (reviewed in Murstein, 1986). In the stimulus stage, prospective partners would be drawn to each other on the basis of perceived attractiveness and other initial impressions. After “checking each other out” in initial contacts, dating couples would proceed to express and compare their values, attitudes, interests, and beliefs to see if they were compatible. The final stage would involve experimenting to find out if the variety of roles each person could play as a member of the couple were satisfying to the other’s needs and expectations.

Communications specialists developed a different way of dividing the life cycle of relationships into parts (Knapp, 1984). The verbal interaction in a relationship was categorized either as facilitating coming together or coming apart. Coming together was subdivided into five stages: initiating; experimenting, or finding common interests; intensifying, or expressing feelings; integrating, or identifying with each other; and bonding, or making formal future oriented commitments such as marriage. Coming apart was also subdivided into five stages: differentiating, which means pinpointing personal differences; circumscribing, or separating out individual activities and privacy; stagnating, or expressing boredom with the partner; avoiding, or arranging to stay apart; and terminating the relationship. Except for the terminating stage, the coming apart stages are not considered “declining” aspects, because both uniting and separating are vital to a continuing relationship, as we shall see in what follows.

For our own account of relationship development we have chosen to expand the traditional stages, because they provide more global categories easily recognizable by everyone. We divide premarital relationships into the following stages: initiating, casual dating, being in love, deepening, decay, and terminating. This sequence eliminates the previous distinction between dating and courtship and focuses more on developmental processes than on the culturally prescribed outcomes of engagement and marriage.

TABLE 1.1. Stages of premarital relationships (Rows indicate roughly equivalent stages.)

Each stage of an evolving relationship contains a different mix of some basic processes, which grow and change in their prevalence, intensity, and meaning for the partners as the relationship develops. These processes include (a) communicating with one another, (b) developing and changing relationship roles, (c) coping with thoughts and emotions in the relationship, (d) being sexual and affectionate, (e) uniting and separating in dynamic interplay with each other, and (f) coping with needs for power and control and dealing with conflict.

The research we will describe in the next three chapters has been gathered among college students. Since our readers are also college students, the empirical basis for our conclusions is appropriate. However, the students sampled in almost all empirical studies have represented only white American culture. Therefore students whose cultures are significantly different from this mainstream should consider what is said here critically. In fact, you should keep the limitations of empirical research in mind no matter who you are, and ask: Do these statistically based generalizations fit for me? And if they do not, why not?

The initiating stage

The initiating stage begins when one person first becomes aware of and interested in meeting the other. Therefore, whether you see someone you would like to meet or just hear about him, the initiating stage of your relationship has already begun. You may spend minutes, hours, days, or weeks thinking about meeting the person before you actually take the plunge. Some people act immediately, while others prefer to dwell in the realm of possibility, gathering information and playing out fantasy scenarios in their minds.

This stage ends when the first agreed upon one-to-one meeting, or first date, ends. But often prospective partners will prolong the initiating stage by meeting numerous times as parts of a group of friends who are not “paired off,” thus avoiding any overt demonstration that they have a “dating interest” in each other. Therefore, for many young people today, the key distinction is between “dating” and “just friends” meetings.

Attraction

How do potential partners meet? About a third of college students report meeting dating partners through a friend (Knox & Wilson, 1981; replicated by first author in 1993). The next most frequently mentioned initial meeting occurs at parties or other special events, such as concerts, dances, vacation spots, and conferences (19% in Knox & Wilson, 1981; 22% in author’s replication). Another significant portion of future dating connections are made through shared classes or work (17% in Knox & Wilson, 1981) or through peer groups and other shared activities (31%). Since over half (and 55% in Murstein, 1986) of dating partners meet through friends or at special events and a lesser number rub elbows at work, in class, or in friendship groups, perhaps the context in which people meet makes a difference.

The numbers indicate that a sudden approach with a comparative stranger seems to be attractive to slightly more young adults than a gradual acquaintance with a person already familiar. Perhaps people who meet in class, at work, or in peer groups are more influenced by hearing group gossip about each other and by seeing each other behave in a socially normal and “friendly” manner, and hence are more likely to feel comfortable and expect to be “just friends.” By contrast, being introduced by a friend can surround the new person with mystery and evoke some anxiety. The friend can turn this into anticipatory excitement by offering only positive and enticing information. Unusual events provide a novel or exciting atmosphere and opportunities for intense one-to-one encounters and flirtatious behavior. The initial high of a sudden approach with uncertainty and high expectations retains its appeal, because research indicates that the greater emotional arousal may contribute to stronger feelings of attraction (Dutton & Aron, 1974; Allen et al., 1989).

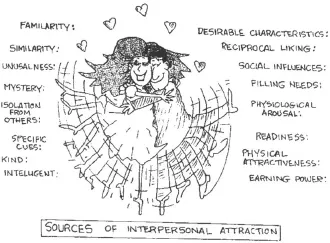

How do people attract each other? Attraction has been studied quite a bit, perhaps because attraction feels so good that it is fun to study. Some of the ways that romantic attraction can come about are listed in Table 1.2.

Though many desirable characteristics have been studied, physical appearance has the most non-rational impact on the most people, so it has received the most research attention. We will consider physical appearance in the context of overall attraction.

If men had more up top, we’d need less up front. (Jaci Stephen)

Physical attractiveness. At first glance, more attractive people are more likely to be viewed as sexy, warm, sensitive, kind, modest, and competent (Dion et al., 1972). A cross-cultural study of thirty-three cultures indicates that all over the world, physical appearance is more likely to be mentioned as an attracting factor by men, while women are more likely to notice a man’s financial prospects and ambition or industrious...