![]()

1

Introduction: the rubber ruler

1.1 WHY TEST LANGUAGE LEARNING?

Language teachers spend a lot of time with their students, both in the classroom during teaching and learning activities, and outside during, for example, office hour visits or field trips. Teachers are constantly attending to their students’ performance in the second language, noting their pronunciation, the breadth and accuracy of their vocabulary, their use of syntactic rules, and the appropriacy of their language use. If asked, for example, how Richard is doing in French, or what progress Paola is making in her English class, most teachers can come up with an evaluation of their students’ learning, perhaps something like, ‘Well, Paola’s pronunciation is pretty good, though she clearly has a bit of an accent, but her knowledge of past tense forms is a bit shaky and she really doesn’t understand relative clauses at all. Her vocabulary is excellent for someone in only her second year of English.’

If teachers are able to assess their students’ progress like this – and most teachers can do something like it by the second or third week of class – why do they need language tests? Perhaps the most important reason is fairness. We like to make sure that we treat all our students the same, giving each of them an equal opportunity to show us what they’ve learned and what they can do with the language they’ve learned. Tests allow us to present all our students with the same instructions and the same input under the same conditions. Tests also allow us to get a ‘second opinion’ about our students’ progress – they can help confirm our own assessments and help us make decisions about students’ needs with more confidence. Tests provide for some standardisation by which we judge performance and progress, allowing us to compare students with each other and against performance criteria generated either within our own programme or externally. Finally, tests make it possible for us to ensure that we judge student progress in the same way from one time to the next, that our assessments are reliable.

Tests also allow other stakeholders, including programme administrators, parents, admissions officers and prospective employers, to be assured that learners are progressing according to some generally accepted standard or have achieved a requisite level of competence in their second language. Achievement tests are based on the actual material learners have been studying or upon commonly agreed understandings of what students should have learned after a course of study. Such tests can inform administrators, for example, that learners are making adequate progress and that teachers are doing their job. Proficiency tests are usually intended to help us make predictions about what learners will be able to do with the language in communicative situations outside the classroom. For example, a test of academic German proficiency can be useful in judging whether a learner has an adequate command of the language to enable her to study history at a university in Berlin. Similarly, a test of English for business can help an employer determine that a job applicant will be able to carry out business negotiations in the United States. These are important educational and social benefits that tests can provide.

Tests are also important instruments of public policy. National examinations, for example, are used to ensure that learners at educational institutions across the country are held to the same standards. Such examinations can also be used in a ‘gatekeeping’ function, to ensure that only the top performers are admitted to the next level of education, particularly in countries where the demand for education outstrips the government’s ability to supply it. Tests are also sometimes used as more direct political tools, to control, for example, numbers of immigrants or migrant workers. Such political uses of tests require particularly careful ethical consideration, and I will discuss this aspect of testing briefly later in this chapter.

In order for tests to provide all these advantages and functions, however, it is necessary that the tests we use are of high quality, that the tests are the right ones for the purposes we have in mind, and that we interpret the results appropriately. That is what this book is about: understanding the various uses of language tests and the process of test development, scoring test performance, analysing and interpreting test results, and above all, using tests as ethically and fairly as possible so that test takers are given every opportunity to do their best, to learn as much as possible, and feel positive about their language learning.

1.2 WHAT IS A LANGUAGE TEST?

When it comes right down to it, a test is a measuring device, no different in principle from a ruler, a weighing scale, or a thermometer. A language test is an instrument for measuring language ability. We can even think of it in terms of quantity: how much of a language does a person possess? But what does it mean to say that we want to measure ability or quantity of language? In what sense can we actually measure a concept as abstract as language ability? To begin to answer these questions, let’s consider just briefly the properties of more ordinary measuring devices.

1.2.1 What are the properties of measuring devices?

At its foundation, measurement is the act of assigning numbers according to a rule or along some sort of scale to represent a quantity of some attribute or characteristic. The most straightforward measurement is simple counting: there are 19 words in the previous sentence. However, we often depend on devices of some kind to measure qualities and quantities: thermometers, rulers, scales, speedometers, clocks, barometers, and so on. All such devices have some kind of unit of measurement, whether millimetres, inches, litres, minutes or degrees. Although we may wish we could blame our scale when we gain weight, we don’t really argue about whether a pound is a pound or whether a kilogram is as heavy as it should be – we generally accept the units of measurement in our daily lives as representing the standards we all agree on. We do, of course, sometimes suspect the scale isn’t working properly, but it’s quite easy to test – we simply weigh ourselves on another scale and hope for better results!

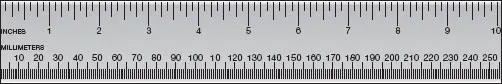

Figure 1.1 Ruler

One interesting quality of many measuring instruments is that the units of measurement are uniform all along the scale. On the ruler pictured above, for example, we could measure an object at any point on the scale and get the same results. Another feature of the ruler is that it has a true zero point, representing a total absence of length. This feature makes it possible to compare two objects directly in terms of their length: something that’s 100 millimetres is twice as long as something that’s 50 millimetres. Moreover, the ruler doesn’t change in size, so that if we measure an object today and find that it’s 100 millimetres long, when we measure it tomorrow, we anticipate getting exactly the same result – unless the object itself has changed in size, as when we measure the height of our children each month to see how much they’ve grown.

To summarise, most measuring instruments allow us to distinguish objects or qualities from each other by assigning numbers to them, and thus to order them in terms of the measurement. The intervals between the units of measurement are equal all along the scale, and there is a true zero point, allowing us to compare the things we measure. Finally, measuring devices we use regularly are reliable: we trust the results and we expect to get the same results every time.

1.3 THE RUBBER RULER

What kind of measuring instrument is a language test? If we were to compare a language test to a ruler, we might say that the language test is like a rubber ruler1. Imagine a ruler that stretched and contracted as you measured things with it. Your two-year-old daughter might be 35 inches tall the first time you measure her, 43 inches the next time and 27 inches the time after that! You could not use these measurements to track her growth, nor could you meaningfully compare her height to that of her five-year-old brother. A rubber ruler would not be a very useful instrument, yet I would suggest that a language test might have many of the properties of such a device. First, there is often great controversy about the nature of the units of measurement in a language test and what they mean. For example, we often talk about students’ language abilities as ‘elementary’ or ‘intermediate’ or ‘advanced’, but each of us probably has a different idea of what those terms mean. Even if we had a test in which we said that a 50 represented an ‘elementary’ level, a 70 was ‘intermediate’ and 90 or above ‘advanced’, we might have a hard time convincing anyone else to agree with us. Second, the intervals between the units are not always equal along the scale. A number of agencies in the US government use a well-known language proficiency scale that goes from ‘elementary’ to ‘native’ in only five steps (Interagency Language Roundtable 2007). It is much easier to get from elementary to the next level (‘limited proficiency’) than it is to get from ‘full professional proficiency’ to ‘native proficiency’. The intervals are not equidistant. Moreover, in a language proficiency scale, there is no true zero point so it’s not possible to say that Nadia knows twice as much French as Mario, even though Nadia got twice as many points on the test. Finally, if we give the test again tomorrow, every student is almost guaranteed to get a different score! So what I’m suggesting is that a language test may not be a very good measuring device. However, all is not lost. There are steps we can take so that even a rubber ruler might be a more useful instrument for measuring things, if it were all we had.

First, there are limits to how far a rubber ruler will stretch, so the variation in our measurements is not endless: there’s an upper limit to how far the ruler will stretch and a lower limit to how much it will contract between measurements. If we know how much ‘stretch’ there is in our ruler, we can at least have some idea of how inaccurate our measurements are likely to be, or conversely, we know something about the level of accuracy of our measurements and how much confidence we can have in them. Second, if you took the three measurements you got with your daughter, above, and averaged them, the average, 35 in this case, might be closer to her true height than any single measurement, and if you took 10 measurements, the average of those would be even closer. So, the more measurements you take, even with a faulty measuring device, the more accurate your estimate of the true size is likely to be.

So it is with language tests. You’ve no doubt noticed that some language tests have a large number of questions. In part this is because language is complex and there are a lot of features to measure, but it’s also because the more opportunities we give test takers to show what they know, the more accurate and fair the measurement is likely to be. Furthermore, there are ways to estimate how much variation – or ‘stretch’ – there is in the measurements we make with our tests and thus we can know how much confidence we should have in the results. We will deal with these and other issues in later chapters, but for now, the point to appreciate is that the most useful language tests are those that have the least a...