eBook - ePub

Fostering Collaboration Between General and Special Education

Lessons From the "beacons of Excellence Projects" A Special Issue of the journal of Educational & Psychological Consultation

This is a test

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fostering Collaboration Between General and Special Education

Lessons From the "beacons of Excellence Projects" A Special Issue of the journal of Educational & Psychological Consultation

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Published in 2003, Volume 13, Number 4 of the Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation. This volume covers looking at 'Beacons of Excellence Schools' what they tell us about collaborative practises and examining special and general education collaborative practise in exemplary schools.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Fostering Collaboration Between General and Special Education by Margaret J. McLaughlin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psicología & Salud mental en psicología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Coteaching for Content Understanding: A Schoolwide Model

Catherine Cobb Morocco and Cynthia Mata Aguilar

Education Development Center, Inc.

Education Development Center, Inc.

This article describes a promising form of professional collaboration: coteaching between a content area teacher and a special education teacher. In an investigation of a schoolwide coteaching model in an urban middle school that places students with disabilities in heterogeneous classrooms, researchers interviewed key school leaders and made detailed observations of coteaching. The study found that although content teachers conduct more of the instruction and special education teachers provide more individualized assistance, both use a full range of instructional roles. Essential to the success of coteaching partnerships were collaborative school structures, equal status rules for teachers, a commitment to all students' learning, and strong content knowledge.

A persistent theme of school reform literature over the past 20 years has been the need for teachers to shift from working as isolated practitioners to working as colleagues. Teachers need to coordinate different kinds of expertise if students are to learn rigorous academic content that reflects curriculum reforms and higher standards (Morocco & Solomon, 1999). Instructional content can be considered rigorous or authentic when it requires students to engage in constructing knowledge, focuses on information and concepts identified as important in a subject area, and engages them in issues relevant beyond school (Louis, Marks, & Kruse, 1996; Newmann & Wehlage, 1995). Given the diversity of student backgrounds and academic needs in our schools, as well as the movement to include students with disabilities in the general education curriculum and classroom, teachers need one another's professional support more than ever.

Correspondence should be addressed to Catherine Cobb Morocco or Cynthia Mata Aguilar, Education Development Center, Inc., 55 Chapel Street, Newton, MA 02458-1060. E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected]

One of the most promising and intricate forms of collaboration in support of diverse learners to emerge in recent years is cooperative teaching between a content teacher and a special education teacher. Coteaching is defined as "a restructuring of teaching procedures in which two or more educators possessing distinct sets of skills work in a coordinated fashion to jointly teach academically and behaviorally heterogeneous groups of students in an integrated educational setting" (Bauwens & Hourcade, 1995, p. 46). Coteaching is of particular interest to schools that aspire to become exemplary in providing all students the academic support they need to be successful.

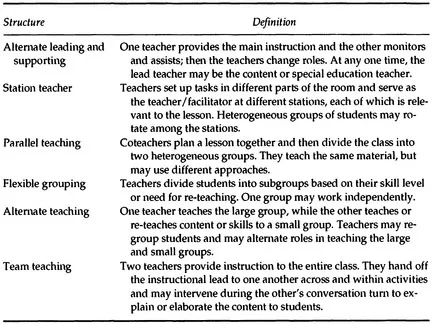

In their study of coteaching in high schools, Rice and Zigmond (2000) listed three criteria for a professional coteaching relationship: (a) two qualified teachers, one of whom is a special education teacher, share the same classroom and students; (b) the teachers share responsibility for planning and teaching an academically diverse class that includes both students with disabilities and typically achieving students; and (c) both teachers deliver substantive instruction. Table 1 summarizes several possible classroom coteaching structures identified in the research literature. In all of these structures, teachers have differentiated roles yet equal status in the eyes of students and other teachers, and both teachers contribute directly to students' intellectual participation and progress. The "alternate leading and supporting" structure looks the most like the traditional hierarchical model in which the content teacher takes the lead in substantive instruction, and the special education teacher helps by managing instruction and behavior and serving as an assistant. Yet, in this arrangement, the two teachers shift between those roles. Each of these structures may reflect considerable variation in practice, and experienced coteachers tend to shift among them even within the same lesson, depending on the demands of the content and students' individual learning needs.

Coteaching research has only begun to study the impact of coteaching structures on students' academic learning (Bauwens, Hourcade, & Friend, 1989; Cook & Friend, 1995; Dieker, 2001; Fernnick, 2001; Fennick & Liddy, 2001; Rice & Zigmond, 2000; Vaughn, Schumm, & Arguelles, 1997; Zigmond & Magiera, 2001). In a comprehensive study of inclusion in 18 elementary and 7 middle schools, Walther-Thomas (1997) found that the lower student-teacher ratio that resulted from the presence of coteachers in normal-sized classrooms led to strong academic progress and enhanced student self-confidence. A meta-analysis of six coteaching studies (Murawski & Swanson, 2001) found that coteaching was a moderately effective procedure for influencing student outcomes and that it had the greatest impact on achievement in the areas of reading and language arts.

TABLE 1

Professional Coteaching Structures

Professional Coteaching Structures

Although current research points to the promise of coteaching for enhancing student learning, it provides limited information about whether the classroom coteaching structures such as those in Table 1 tend to take place individually or appear together in classrooms, and what kind of organizational support coteaching requires. Most current research focuses on individual classrooms rather than schoolwide models. The research reflects current practice, because coteaching tends to be implemented piecemeal by a few innovative teachers rather than as a whole-school practice (Murawski & Swanson, 2001; Walther-Thomas, 1997).

Schoolwide models are likely to embrace a broader concept of coteaching that links classroom teaching arrangements with a wider array of instructional roles beyond the classroom. The reference to planning in Rice and Zigmond's (2000) second criterion points to the presence of other dimensions of coteaching besides in-class teaching. Collaborative practices that are associated with effective coteaching and extend beyond the immediate classroom include assessing student work (Allen, Blythe, & Powell, 1996; DiGisi, 1999), curriculum planning and design (Swiderek, 1997; Tanner, 1996; Walther-Thomas, Bryant, & Land, 1996), and monitoring students' progress (Coben, Thomas, Sattler, & Morsink, 1997; Hobbs & Westling, 1998; Janney, Snell, Beers, & Raynes, 1995).

Collaborative practices associated with coteaching require organizational support. Walther-Thomas (1997) identified two organizational structures that promote schoolwide coteaching—interdisciplinary teaming and heterogeneous grouping. Interdisciplinary teams, particularly at the middle school level, share a group of students and ideally take responsibility for the curriculum, instruction, and evaluation for their group (Alexander & George, 1981; Arhar, 1992; Legters, 1999; Zorfass, 1999). If coteaching is to result in positive academic learning, other organizational supports for coteaching may need to include the following:

• Consistent, protected meeting time for coteachers to coordinate their classroom work (Bauwens, Hourcade, & Friend, 1989).

• Practices that enable the coteaching pair to get to know their students well and thus anticipate their academic support needs—for example, advisories (i.e., a mentoring relationship between a teacher and a small number of students; Little & Dacus, 1999) and "looping" (i.e., students staying in a team over two years or more; Maclver & Epstein, 1991).

• Schoolwide commitment to a rigorous academic curriculum (Jorgensen, 1995; Redditt, 1991).

• Active participation of parents in students' academic learning (Field, LeRoy, & Rivera, 1994; Lipsky, 1994; Redditt, 1991).

One limitation of current research is that it mainly provides information about coteaching in elementary grades. Zigmond (2001) found that "except for a single study by Boudah, Schumaker, and Deshler (1997), which showed a slight decrease in test and quiz scores for students with disabilities in cotaught classrooms, there has been virtually no study of coteaching at the secondary school level, despite its widespread adoption" (p. 71). Boudah et al. (1997) pointed out the need for coteaching research at the secondary level, where an older student population, increasing curriculum demands, and resource and scheduling constraints directly impact programs. The absence of research on coteaching is echoed in the middle grades and is surprising given the thrust toward both teacher and student collaboration in the middle-grades reform movement (Carnegie Council on Adolescent Development, 1989) and the extensive literature on the benefits of interdisciplinary teaming and clustering (Gable, Hendrickson, & Rogan, 1996; Gable & Manning, 1997; Howell, 1991; White & White, 1992). Further, we need to know whether this collaborative practice is effective in the large and increasingly culturally diverse middle schools in both urban and suburban communities in our country.

Another limitation is that we have little knowledge of what these coteaching arrangements look like in action or how teachers negotiate the demands of the subject matter and their students' needs. To understand and implement schoolwide coteaching, teachers and administrators need to know how the collaboration works "on the ground." We need to understand the extent to which the special education and content teachers differentiate their roles, and whether coteaching pairs across a school differentiate their roles in the same ways. Weiss and Brigham (2000) called for data that provide microlevel examples of the roles played by the two teachers and the interplay of those roles during teaching. Given the IDEA 1997 mandate to include students with disabilities in the standards-based general education curriculum and, to the extent appropriate, in general education classrooms, we need to better understand how collaborating teachers can engage students with disabilities in rigorous content that requires higher level thinking.

Purpose of the Analysis

This article responds to the need for research on schoolwide coteaching models in the middle grades and for "close-up" data on the classroom coteaching process in rigorous learning situations. It addresses the following research questions:

- What is the school's vision and model of coteaching? How has the school put that model into practice?

- What coteaching roles do teachers use in their classroom instruction? How do those roles vary across pairs and teams?

- How can coteaching engage students in understanding rigorous content? Given the current mandate to include all students in standards-based instruction, we wanted to understand how coteaching might provide academic support within a challenging curriculum.

The investigation examined these three questions in a low-income, culturally diverse middle school that instituted a model of inclusion and coteaching in 1995, then modified that model and brought it schoolwide over the next 3 years. These questions require diverse data gathering methods. We draw mainly on interview and classroom observation data to present this coteaching model and describe how teachers implemented it across three interdisciplinary teams. Both classroom and organizational structures are a part of putting the vision into practice.

This coteaching research is part of a larger study of three urban middle schools in the Beacons of Excellence project funded by the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs. The goal of Education Development Center, Inc.'s (EDC) Beacons of Excellence project was to identify three urban middle schools that were making rigorous content learning accessible to their low-income, culturally diverse students, including students with disabilities, and achieving positive results on high-stakes tests (Aguilar & Morocco, 2000; Morocco, Clark-Chiarelli, Aguilar, & Brigham, 2002). We selected the three schools through a national nomination and application process, using selection criteria that included dimensions of effective middle schools identified by the middle-grades reform movement: academic excellence, social equity, and developmental responsiveness (Lipsitz, Mizell, Jackson, & Austin, 1997). A fourth criterion was that schools included students with disabilities in heterogeneous general education classrooms. From 40 applicants, we selected three urban, high-performing, inclusive middle schools, located in the South, the Midwest, and the Eastern seaboard.

This article focuses on the Beacons school in the South, particularly the coteaching approach that was well established in the school by the time of the study. A feature of the school that stood out in the original selection process was its integration of an inclusive approach—coteaching—within a larger middle-grades reform approach involving interdisciplinary teaming. Unique in many respects, this school is also representative of the cultural and linguistic variation of many middle schools, with its strong migrant population, new Latino immigrants, and high percentage of students identified as having special needs. The article draws on observations of the process of coteaching in three interdisciplinary teams at three grades levels in this Beacons school. Our goal was to understand how teachers engaged in coteaching within and across their interdisciplinary teams, and whether and how they used this collaborative practice to assist students, including those with learning difficulties, in rigorous learning activities to build their understanding of important information and concepts in the major subject areas.

Method

School Setting

Dolphin Middle School is located in a large mixed-income county in the southern part of the United States. The school was established in 1994-1995 as a reconfiguration o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Copyright

- Editor's Note: Acknowledgments

- SPECIAL ISSUE Fostering Collaboration Between General and Special Education: Lessons From the "Beacons of Excellence Projects"

- Examining Special and General Education Collaborative Practices in Exemplary Schools

- Indicators of Beacons of Excellence Schools: What Do They Tell Us About Collaborative Practices?

- Coteaching for Content Understanding: A Schoolwide Model

- Collaboration: An Element Associated With the Success of Four Inclusive High Schools

- COMMENTARIES

- Collaboration to Benefit Children With Disabilities: Incentives in IDEA

- Moving From Abstract to Concrete Descriptions of Good Schools for Children With Disabilities

- Index to Volume 13 (2002)