This is a test

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Europe Unbound provides an analysis of the enlargement of the European Union and examines from both a theoretical and a political approach issues such as:

* Where does Europe end?

* Should Europe's borders be open or closed?

* How does the evolution of territorial politics impact on the course of European integration?

This book draws upon such diverse fields as History, Sociology, Political Science and International Relations and contains contributions from an international range of respected academics.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Europe Unbound by Jan Zielonka in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

Boundary making by the European Union

Jan Zielonka

Europe’s borders are again in flux, causing problems and anxiety. The Cold War border between the East and West was imposed arbitrarily in defiance of history and culture, but it was firm and stable. There was little trade and mobility across this border, and those who did venture to cross it were subjected to strict and often humiliating scrutiny by border guards with dogs and machine guns. However, in 1989 a euphoric crowd dismantled the Berlin Wall – the epitome of the East–West border. The Soviet empire subsequently collapsed, partly because the idea of making Europe ‘whole and free’ motivated resistance to it. Yet the legacy of the Cold War divide persists and Europe has found it difficult to resolve the complex issues of borders, frontiers and mobility.1

The European Union is the key actor trying to cope with these new border issues, and one of its prime strategies in this endeavour is to enlarge to the East.2 However, implementation of this strategy is confronted with mounting practical problems and conceptual dilemmas. Various gaps in terms of democracy, economics and culture still persist despite all efforts to make both parts of Europe more compatible. Accepting new and to a degree incompatible states into the Union cannot but affect the already existing system of European integration. Enlarging the Union to include only some, more compatible post-communist countries replaces old dividing lines by new ones, with potentially destabilizing implications for the entire continent. Moreover, the key aspects of European integration – the single market and the Schengen system – make it more rather than less difficult for outsiders to enter the integrated European space. While internal borders among EU member states are gradually being abolished, external EU borders are being tightened up. The Schengen Manual for the External Frontier, containing common rules that provide for strict controls, has added to a series of other judicial and security measures envisaged by the Schengen Convention. Those who aspire to join the Union are asked to comply with the Schengen acquis and harden their borders.

Although the Schengen regime is largely about the free movement of people, judicial assistance and police cooperation, in some sections of public opinion in Eastern Europe it has come to be regarded as an imposed regime with discriminatory implications. For many in the post-communist part of Europe, Schengen has become a symbol of exclusion of the poor and allegedly less civilized European nations by wealthy and arrogantly superior ones.3 The problem is not only about a rising gap between symbolic politics and realpolitik, the former reflecting psycho-cultural anxieties, the latter relating to legal and administrative necessities. Since the fall of communism, the Schengen system has evolved in a direction not originally envisaged by the signatory states: the fears of mass migration from an impoverished and crisis ridden ‘East’ have prompted West European governments to reassure their voters that the abolition of internal EU frontier controls would be complemented by the preservation of tough external border controls. Thus the implementation of Schengen has been accompanied by a new emphasis on tightening up of immigration controls, curbing flows of asylum seekers, increasing visa restrictions, widening the scope of secret data collection on personae non grata and mixing crime and migration. The terrorist attacks on New York and Washington DC on 11 September 2001 reinforced further the arguments for tightening up borders, including those in Europe.

This book attempts to analyse this complex set of problems from both a political and a theoretical perspective. It is about the evolving nature, characteristics and scope of EU borders. The scope of borders largely depends on the degree of diversity the Union is able to import and digest in the course of enlargement. It also depends on the reaction of external actors to an EU with an ever-greater geographical reach. The nature of borders largely depends on the degree to which these borders are open or closed and the extent to which they are part of the EU governance system rather than limited to national systems. The type and scope of borders may well be determined by different factors, but they are closely interlinked. For instance, the Union may well afford to have a ‘fuzzy’ type of border with Slovakia (assuming this country is not included in the first wave of enlargement), but not with Russia or Iraq (after eventual inclusion of Turkey). Also the internal and external characteristics of borders are closely interlinked. These linkages are even more crucial if we approach the borders from a theoretical perspective of governance and state building.

This book devotes special attention to the problems resulting from the installation of a relatively harder EU border as envisaged by the Schengen regime and the single market. A hard border sharpens the distinction between members and non-members of the EU, producing an exclusion complex. It makes a great difference in both objective and subjective terms whether a country is on the right side of the border. Hence, the pressure for EU membership is growing and is becoming unmanageable. A hard border seems also at odds with the pressures on the EU from global economic competition. Globalization and interdependence may render prohibitive the costs of controlling the flow of goods, capital, services and people across borders. Moreover, the main argument used to justify the hard external border does not seem plausible. There is little evidence that attempts to control terrorism, international crime and migration at the EU’s rigid border are effective. In fact, a hard border creates extra demand for organized cross-border crime.

It can also be argued that the ‘fortress’ impulse undermines the coherence, moral authority and international credibility of the EU. The future scope of EU borders is important, but so is the nature of the future EU border regime. Defining the borders of the EU should not imply closing them. Of course, borders by their very nature divide and exclude. However, the actual (and desirable) degree of exclusion and access should be carefully scrutinized. Likewise, there is no reason to treat EU borders in state-centric linear terms. The linear concept of a border emerged only some 150 years ago, and it is linked to an absolute and now largely outdated notion of sovereignty. More flexible types of border arrangements worked well in various historical contexts, starting with the Roman concept of limes or the French concept of marche, both treating the border more as a geographical zone than a clear line. In fact, for centuries East Central European countries had loose border areas and ‘marches’ rather than sealed types of borders.

However, can one apply medieval concepts to modern or possibly ‘post-modern’ institutions such as the European Union?4 What would a soft, flexible and functionally overlapping border regime imply in practice? And can one restore loose ‘limes’ or ‘marches’ in a Europe characterized by a much different types and levels of cross-border mobility? This book assumes that it is virtually impossible to address these kinds of questions in a purely technical or administrative manner. This is because borders ‘are not simply lines on maps where one jurisdiction ends and another begins. … Borders are political institutions: no rule-bound economic, social or political life can function without them.’5 In fact, Max Weber and generations of his disciples have argued that the whole history of human organizations could largely be read as a series of continuing efforts to bring territorial borders to correspond to and coincide with systemic functional boundaries, and to be in line with the consolidated socio-political hierarchies of corresponding populations.6 This book will look at the EU’s borders from this broad theoretical perspective.

This introductory chapter cannot do justice to all the diverse, complex and at times conflicting arguments elaborated in this book by individual authors. But I will try to show and explain the sequence, rationale and implications of these arguments, and point to their broader theoretical context. I will first demonstrate the crucial role of borders in shaping the very nature of political systems. The extension of this argument is that the scope and type of borders of the Union will determine the profile of the EU itself. Second, I will try to assess the future scope of EU borders resulting from enlargement. The further the Union expands, the more diversity it will import. This will have serious implications for the Union’s cultural identity, economic path of development and model of government. The geopolitical implications of extending the EU further east and south will also be very serious. For all these reasons, the Union cannot expand endlessly, even though there is no rational or ‘natural’ way to draw boundaries of the European Union. I will therefore argue that the Union is likely to remain ambiguous about its future reach. Expansion is set to be open-ended, incremental and based on largely arbitrary and often vague criteria. This will shape the nature of Euro-polity and influence its neighbours’ reaction to it. Third, this introduction examines various possible border types. What will determine the degree of openness and closure of EU borders? Are these borders to be administered by the Union or by individual member states? I will show in particular that maintaining a hard border regime is increasingly difficult in practice, but also politically damaging, especially vis-à-vis law-abiding and economically prosperous East European countries. But I will also argue that the degree of permeability of borders cannot be totally divorced from the issue of European geo-strategy. The final section will try to assess the evolving nature of EU borders in the process of eastward expansion. The evidence points to the ongoing change in the scope of these borders, increased disharmony between different types of borders and the emergence of fuzzy border zones to replace the carefully guarded existing border lines. As a consequence, the Union may increasingly come to resemble a neo-medieval empire rather than a Westphalian super-state.7 The architects of enlargement should take account of these broader implications of boundary re-modelling.

Systems and their borders

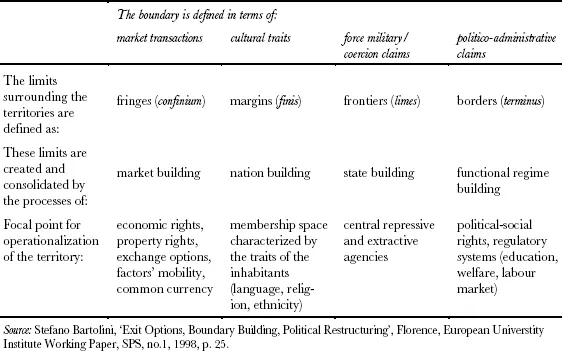

The concepts of frontiers, borders and territory are historically determined. They have meant different things at different times and they have been employed for different historical purposes. The 1648 Peace of Westphalia symbolized the advent of territorial politics.8 It was at that time that the ideal of a sovereign state controlling a given territory became prevalent. This was later to be paired with the ideal of the sovereign people carried on the banners of the French and American revolutions. But as Charles Maier argues in his chapter, modern territoriality and the modern nation-state are not just a consequence of ideological developments or legal treaties. They also depend upon the material and administrative possibilities for controlling large regions on the ground. Such possibilities emerged in the second part of the nineteenth century with the development of modern forms of transportation (especially railroads), and the successful centralization of government. Only then, Maier argues, did a new awareness of ‘bounded space, a preoccupation with fixing border lines, with the demarcation of insiders and outsiders, public and private’, become truly the reality. Borders were seen no longer as zones, but as sharp lines separating largely homogenous and centrally governed nation-states. In other words, a strict overlap was provided between administrative borders, military frontiers, cultural traits and market transaction of individual states. Table 1.1 illustrates these different types of territorial boundaries of modern states indicating processes that led to their creation and consolidation.

However, one should ask two basic questions. Is this ideal of a sovereign territorial state still valid in the twenty-first century? And can we apply this ideal of a territorial state to the European Union? Several chapters in this book provide negative answers to these questions, but usually with some important qualifications.

Charles Maier in his chapter shows how globalization is undermining the capacity of nation-states to maintain discrete political, cultural and economic space within their administrative boundaries. In his view, the decisive changes took place between the late 1960s and the end of the 1970s. National economic sovereignty in particular has been eroded by massive international labour and capital flows that constrain governments’ abilities to defend their countries’ economic interests. The economic basis of public life has also been reoriented with the demise of Fordism. Moreover, the basic class configuration that created the old territorial order has disappeared: ‘the new elite at the centre reaps the rewards of being adept at transnational control of information and symbols,’ Maier argues.

Table 1.1 Types of territorial boundaries

Pierre Hassner in his chapter also points to the evolving trend towards ‘interpenetration between the interior and the exterior of states and organizations’ producing virtual ‘de-borderization’. Christopher Hill confirms that theorists of politics and international relations increasingly call into question polarities such as those between the domestic and external environments, between the state and world society, and between agents and structures. Several other chapters clearly show that it is no longer possible to control trans-border flows, suppress multiple cultural identities or defend particular lines of demarcation. Ewa Morawska, Eberhard Bort, Didier Bigo and Malcolm Anderson illustrate, in particular, that even carefully guarded and technically well-equipped borders can hardly stop terrorists, criminals and other unwanted migrants in an age of cascading interdependence and globalization. The tragic events of 11 September 2001 have led to further tightening of border controls, but they are unlikely to halt the ongoing process of globalization and interdependence.

The notion of a sovereign, territorial state has thus been eroded and it is far from certain that the European Union itself will ever become such a state. So far, the European Union has been anything but a classical territorial state. It has no proper government, no fixed territory, no army or traditional diplomatic service – it even lacks a normal legal status.9 The Union increasingly acts in concentric circles or variable geometry due to various opt-outs negotiated by individual member states in the areas of foreign, monetary or social policy. At the same time its laws and regulations are increasingly being applied by East European states that are not as yet EU members. The Union also lacks a strong and coherent sense of cultural identity, let alone of a European patria. Nor is there a European political demos. In short, a particular form of territoriality – ‘disjointed, fixed, and mutually exclusive’, to use John Gerard Ruggie’s words – is no longer the basis of political life. In fact, Ruggie argues that the Union is a champion in ‘unbundling territoriality’.10

Other scholars disagree with this assessment. In their view the Union is in a process of acquiring all the characteristics of a territorial state and we simply lack a sufficient time-perspective to make a proper judgement concerning its progress. Besides, the demise of territoriality is not assured either. There are strong arguments for trying to prevent such a demise, and in fact various political forces are trying to raise rather than lower borders and to reinstate sovereign authority within them. Pierre Hassner in his chapter talks about ‘nostalgia for roots and for walls’ as a reaction to ‘new nomadism’ t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of tables

- List of contributors

- Preface

- List of abbreviations

- 1 Introduction: Boundary making by the European Union

- 2 Does Europe need a frontier?: from territorial to redistributive community

- 3 Fixed borders or moving borderlands?: a new type of border for a new type of entity

- 4 Facing the ‘desert of Tartars’: the Eastern border of Europe

- 5 Where does Europe end?: dilemmas of inclusion and exclusion

- 6 The geopolitical implications of enlargement

- 7 Ethnic minorities and long-term implications of EU enlargement

- 8 Politics versus law in the EU’s approach to ethnic minorities

- 9 Transnational migration in the enlarged European Union

- 10 Illegal migration and cross-border crime: challenges at the eastern frontier of the European Union

- 11 Border regimes, police cooperation and security in an enlarged European Union

- 12 The future border regime of the European Union: enlargement and implications of the Amsterdam Treaty

- Index