![]() Part 1

Part 1

Reputation as a strategic approach![]()

1

A brief history of strategic thought

What strategy is about, what ideas have been most influential in strategic management and why the need for a new approach, where this book makes its contribution.

Before explaining what we mean by reputation and its management it is worth stepping back to see where our thinking stands in the short history of formalized thinking about the strategy of organizations. A brief history of strategic thought will help to explain the need for a constant evolution of thinking as to how organizations should be managed and where gaps are appearing between the nature and needs of business and such thinking. We believe that a reputation perspective is a timely addition to existing approaches to strategic management.

An organization is by definition something that has form. A business organization is something that also has a specific purpose, to achieve something in its business environment, a goal. It pursues its goal in the interests of its owners, often its shareholders, or on behalf of a wider and more diverse group, its stake-holders. How a business plans to achieve its goals has become known as its strategy, a military metaphor that implies that business is about conquest, battles that are won or lost, about campaigns and resources. This, rather dramatic, view of business management is not quite how strategy works within a real business. Strategy is often more subtle.

It is not always clear to managers how their business should be managed over the longer term. What to do day to day is clear enough (if there was only the time to do it all), but what of the long-term survival of the organization? A useful point to emphasize here is the word ‘long’; the word ‘strategy’ has become abused somewhat and used to decorate anything associated with business, to any short-term initiative so as to make it appear more important. In this book the word ‘strategy’ is always used to refer to something that will take time to evolve, something that will guide a business over a time period measured in years rather than months and something that will lead a commercial organization towards improving its financial performance. We do not limit ourselves to such organizations and recognize throughout that many organizations are not profit maximizers or even profit seekers.

Early books on business strategy aimed to structure and codify the many company histories and memoirs of business leaders. They contained precious little theory or models drawn from economics or other social sciences. They did contain many good ideas but few frameworks in which to place them. There was limited guidance as to when and where any one idea would or would not work. Just because an idea was useful in one company at one moment in time does not mean it will always work. Gradually ideas and models emerged that provided the necessary structure to the chaos of anecdotal memories.

What is strategy in a business context?

First we need to distinguish between corporate and business level strategy. At the corporate level businesses need to ask themselves fundamental questions such as ‘Which business should we be in?’ At the business level a business needs to ask itself, ‘How do we compete?’ It is at this latter level that we position our thinking. The organization has decided that it will compete in a certain market and is seeking ways to optimize what it does in pursuit of its goals, in other words what its strategy should be.

How we think about business strategy has evolved and changed as new and better ideas have become more widely known and accepted and as the needs of business have changed. Business strategy has had many definitions but these are two that give a sense of what is involved irrespective of where we are in time: ‘Strategy is about matching the competencies of the organization to its environment. A strategy describes how an organization aims to meet its objectives’.

The changing environment for any business can be understood by assessing the main factors that create change in a marketplace: political (including legislative), economic, social and, technological trends. If strategy is about matching your business to the opportunities and challenges of the environment then it pays to understand what that means and how the environment is changing and likely to change in the future.

A company’s ability to match itself to its environment can be assessed in turn by listing its main strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats, the now familiar SWOT analysis. PEST and SWOT analyses have become the logical starting points for any business looking to appraise itself and to define or redefine its strategy. How a company matches itself to its environment is left to its management to decide. We believe that it is time to identify better ways in which any organization can identify how to match itself to the changing needs and views of the most important part of its environment, its customers. We also believe that management needs to look more inside their organizations to find the answers to the challenges presented by their environment.

A third definition of strategy explains why commercial organizations should invest time and money in creating a strategy: ‘A successful strategy is one that achieves an above average profitability in its sector’.

We also believe that any approach to strategy must be capable of demonstrating that it can guide a business organization to above average profitability or at least to an increase in profitability. For not-for-profit organizations the performance measures will be very different. A business school might aim merely to break even but measure itself by the number of students it educates. A charity might measure its total giving or a ratio of donations to income. A church might measure itself by the size of its congregation. In this book we tend to use performance measures that are relevant to commercial business but the same logic can be applied to any type or style of organization.

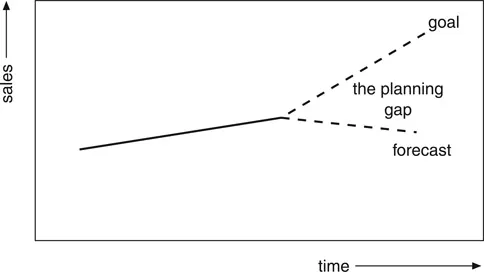

Gap analysis

While companies still use SWOT and PEST analyses, other strategic tools have become dated as business has changed in its nature. A century ago the multinational was the exception on the corporate landscape. Most businesses were small and local and this is still true in many countries and in many sectors to this day. In markets where competition is fragmented and the main competitors are small, a relatively unsophisticated business plan, one that concerns itself solely with the business itself and its immediate market, is likely to be more than adequate. Gap analysis is still a relevant technique that can focus the management of such organizations into thinking about the main issues they face, specifically how to bridge the gap between their existing financial performance and where they would like the business to be in the future. If the gap is wide (Figure 1.1) and if the recent performance has been poor it is likely that the company will have to reinvent itself and to find a different answer to the question ‘What business are we in?’ Used in conjunction with a PEST and SWOT analysis a firm can construct a clear sense of direction. By identifying and costing various projects that will help to fill the strategic planning gap, it can create a strategic plan.

The value of gap analysis lies in its simplicity, but it has one key weakness. It ignores competition. It also lacks any model to help management decide what to do or how to appraise their ideas as to how to fill the planning gap. But first there is a question on the way strategies actually evolve. Is it via the purposive analysis implied by Gap, SWOT and PEST analyses?

Are strategies always deliberate?

There has been a lively debate as to whether ‘strategy’ is something that senior management can decide upon and impose upon an organization or whether strategies emerge from within an organization, guided by managers rather than decided by them, Mintzberg (1987). Many argue that specific strategies tend to emerge, rather than be created, in larger organizations because many new and different strategies are constantly being created and acted upon routinely through the interaction between the firm and its customers or even suppliers. An order might arrive from another country and before it knows it the firm is in the export business. An existing customer, impressed by what the firm has done in the past in supplying one product or service, asks it to provide another outside its normal scope of operation. It does so successfully and finds itself in a new business. This idea of a business almost lurching from one opportunity to another may appal, but the analogy of strategy as evolution where a series of often random events occur, a tiny minority of which change the business because they produce sustained sales or profit, is not too far from reality. Indeed some have argued that you can apply this thinking outside of the firm, one business species thrives as it adapts to a changing environment while another is wiped out when its main source of nourishment declines.

In reality businesses do, indeed must, try to formalize their strategies, to take control of their own destiny. The problem is how? The best answer will probably be a combination of direction and evolution. From the top or centre will come an analysis and formal plan. This will include the financial objectives of the firm, as there is no sense in delegating those. The contribution from lower down the organization, the bottom up component can include the source of options to be analysed. The role of the planner is to select the best options so that the firm has a clear direction to follow. The worst possible situation is where the company is actively trying to pursue more than one competing strategy at the same time. It does not work.

The problem with such thinking is that it leaves the role of strategy formulation somewhat in limbo. On the one hand we are saying that strategy is about having a clear understanding of how the organization is planning to meet its objectives. On the other we are arguing the value of allowing radical ideas to emerge from the customer interface, somewhere not always regarded as the place where strategy is formed. So just where do we stand on the issue of who are responsible for strategic management?

What is best left to the senior team in our view are decisions about which markets to be in, whether to enter country X this year or next, whether to acquire Company Y or to divest Division A, what we labelled earlier as corporate level strategy. Our focus is on market strategy, what organizations should do to manage their way in markets they are already in and intend to stay in. For the first type of decision we concede the need for a centralized function that makes decisions. For the second type of role we will argue that managers should create a framework and set objectives and then let the organization get on with meeting those objectives.

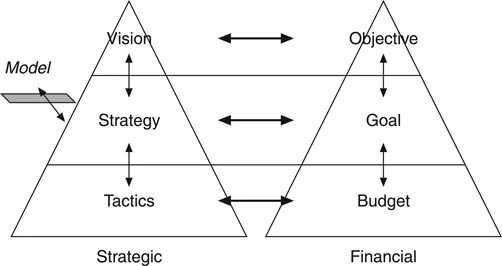

Two flows of ideas

The strategy process is about flows of ideas and instructions up and down the organization. There will be two distinct flows in any business, the financial planning flow and the strategic planning flow. They interact (Figure 1.2) and often conflict. A typical financial objective might be to achieve a 24 per cent return on assets employed each year. A typical vision statement is more qualitative and more long-term, to be market leader in a specific field. Underpinning the company vision will be a strategy that gives practical form to that vision. At the same time it explains how the company expects to achieve its financial goals and objectives. All too often it is far from clear in written plans how the strategy will deliver the required financial performance.

Figure 1.2 The two planning flows.

Tactics are the shorter term, day-to-day matters that will be of relevance to many employees, for example a sales target of four customer calls a day, a production plan for 50 tonnes of product. Money is required to fund the business and to meet day-to-day expenditure. Typically a financial budget is prepared for every part of an organization. Individual budgets are totalled and compared with the revenue forecasts to judge the viability of the plan.

Those reading this who have prepared budgets and forecasts know only too well that preparing them is an art as well as a science. The art comes in not leaving yourself with too little fat, in slightly over forecasting a budget and under forecasting a revenue stream. Those reading this who manage those who prepare budgets and forecasts recognize that managers ‘suffice’ rather than maximize profit, and probably have a number of ways of ensuring that both forecasts and budgets appear challenging while still being feasible. There is a danger in our experience of believing one’s own forecasts. Senior managers spend time and effort making sure that the next year’s plan looks sound because revenue and expenditure balance. But what appears on paper is no more than a wish list. If the organization is in a stable environment then a simple extrapolation from last year is adequate. In such a case the financial flow will dominate management thinking. In situations where the environment is more fluid and less predictable then rigidity creates myopia. Organizations in the service sector have to be prepared to change, often on a daily basis to respond to shifts in what their customers want or in what their competition are doing. Visionary companies often out perform financially driven ones because there is not a reliance upon budgeting and forecasting, there is often not enough time to do such things as the business is too concerned with how it can cope with the opportunities that are there in the market and that can never be predicted. Having a rigid top down approach can stifle the very essence of an organization’s ability to succeed. Senior management’s role is to set targets and let middle and junior managers decide or at least influence how to meet them. As organizations become more complex and physically larger, it becomes more and more impossible for one person at the top to be able to manage ‘top down’. Education standards have risen but companies can ignore the potential they recruit, trying to control what they should be letting free, lacking the framework that will guide employees to achieve without detailed manuals on what to do and how to do it.

In this book we aim to present an approach that is not budget driven in the sense that the firm relies upon replicating what it did last year, but not so free and easy so that senior management lose all control over what is happening.

The balance between the two flows in terms of the relative power they have in the...