![]()

REWARDS, RISKS, AND INTIMACY DILEMMAS

When a couple shares a deep intimate connection they hold a source of meaning and purpose, happiness and companionship, relief from loneliness, and comfort and support (Prager, 1995; Prager & Roberts, 2004). When we have a confidante, someone with whom we can share our private thoughts and who offers us emotional support, tenderness, and devotion, we thrive, physically and psychologically. We handle stress more effectively, and we are more optimistic about life (Prager, 1995). The presence of a confidante in our lives boosts our life satisfaction and buffers us from the detrimental effects of life's daily stresses. Intimacy is one of the most treasured aspects of marriage and other couple relationships, and is at the heart of a couple's connection.

However, the promise of intimacy is also its risk: the more intimacy two people share, the more power they give to each other to cause hurt. An intimate who knows our fears and vulnerabilities can wound deeply with harsh words. Even a sensitive and thoughtful partner will sometimes act in callous, hurtful ways. Every individual seeks and finds his or her own balance between seeking the rewards of intimacy and defending against intimacy's inherent risks.

When individuals come together to form a couple, the partners together engage in a behavioral pattern of reciprocal influence that helps them to maximize intimacy's rewards and minimize its risks. A couple's pattern of intimate relating combines inviting, approach behaviors with defensive behaviors that protect against hurt. It is built from each individual's characteristic ways of handling stress and from the unique chemistry of the partners' influence on one another. Patterned interactions in turn shape an ongoing emotional climate for the couple that further influences their ability to maintain a deep intimate connection. In this chapter, I describe the rewards and risks that couples must weigh to form and sustain that deep intimate connection.

Intimacy can defy definition in that there is no single definition upon which scholars and clinicians agree (Prager, 1995). With the definition below, I hope to capture the characteristics of a single intimate interaction and the ongoing experience of intimacy in a long-term couple relationship simultaneously.

What Is Intimacy?

Intimacy has been difficult to define because the word refers to several different but related concepts. The most influential definition conceptualizes intimacy as a certain type of interaction (Reis & Shaver, 1988). According to Reis and Shaver, intimacy in interactions has two dimensions: (1) self-disclosure and (2) validation, caring, and understanding in the receiving of the other's self-disclosure. An intimate interaction is one in which we share ourselves, risking hurt should the partner make an insensitive response (Cordova et al., 2005). Second, two people are intimate when they share a kind of deep, warm, loving emotional connection. David Olsen and his colleagues developed a measure called the Personal Assessment of Intimacy in Relationships (PAIR; Schaefer & Olson, 1981) whose conceptual underpinnings highlight this aspect of intimacy. The PAIR measures the experience of connection in multiple aspects of the relationship, including recreational, intellectual, sexual, emotional, and spiritual intimacy. Intimacy can refer to the quality of the couple's interactions and feelings of connection within a specific relationship domain and can also refer to a type of relationship (Prager, 1995; Reis & Patrick, 1990), one that includes numerous and frequent intimate interactions and the warm, supportive relationship climate that permits such interactions to occur with safety. Finally, intimacy has been used to refer to the personal, private information that is only shared with select others.

What these three intimacy concepts have in common is the assumption that intimacy refers to the sharing of something personal and private about the self, something that is not ordinarily available or accessible without the person's invitation and consent. Part of what we cherish about intimate sharing is the understanding that our partners are sharing something exclusively with us, whether that intimate sharing is limited to exclusive sexual contact, or includes shared secrets and tearful confidences.

Dimensions of Intimate Interactions

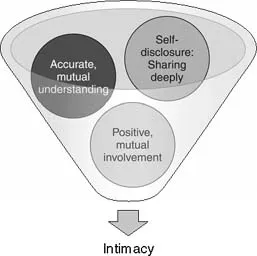

Intimate interactions are defined by three aspects (shown in Figure 1.1): self-revealing behavior, positive involvement with the partner, and accurate, shared understandings (Lippert & Prager, 2001; Prager & Buhrmester, 1998; Prager & Roberts, 2004). Self-revealing behavior is the necessary defining feature of intimate relating and refers to verbal self-disclosure, sexual contact, physical closeness, and expressions of affection. Verbally intimate partners share themselves freely and unself-consciously, allowing the partner a window into their inner lives. Verbally intimate partners frequently express their positive feelings for the other.

Less verbal individuals can also enjoy frequent intimate interactions. Frequent sexual contact, frequent hugs, kisses, tender touches, caresses, and frequent hand-holding can all be intimate expressions. Positive involvement

Figure 1.1 Three components of intimacy

refers to attentiveness and immediacy in communication and conveys positive regard for the other person. Immediacy increases the level of emotional contact between partners and includes the use of first person and present tense in verbal communication, as in the statement, “I appreciate everything that you do for me” versus “What you've done here is very much appreciated.”

Positive involvement refers to an appreciative attitude toward the partner and the partner's disclosures. This does not mean that interactions are intimate only when partners are expressing positive emotions. Rather, intimate interactions can encompass the full range of emotions. Positive regard is an attitude that intimate partners have toward one another. Specific behaviors associated with positive involvement include listening to the partner's communication and demonstrating acceptance of the partner's expressions as his. It refers to affectionate touch that communicates pleasure from touching and being touched by the partner and an acceptance or appreciation for the partner's body. Intimate touches convey warmth, love, attraction, and affection. They convey positive regard.

Finally, intimate relationships are built upon shared understandings of each partner's inner self that are revealed in intimate interactions. In an intimate interaction, both partners gain access to or learn more about the other's inner experience—from private thoughts, feelings, and beliefs, to characteristic rhythms, habits, or routines, to private sexual fantasies and preferences. Intimate relating is at core two selves knowing each other deeply and thoroughly. This knowledge endures beyond a particular interaction and informs and deepens the intimate relationship.

In conclusion, an intimate interaction is one in which partners grant one another access to the most private aspects of themselves: to their bodies, to their psychological selves, and to that which they value highly. An intimate relationship is one in which partners have extensive mutual knowledge of one another's selves and offer each other a loving, respectful attitude toward that which is private and vulnerable within. The result of intimate interactions with the partner is the perception on the part of each that the one understands the other as they each understand themselves and accepts the partner's inner life as it is.

The Need for Intimacy

Although not everyone desires the same level of intimacy in their relationships, most people want some intimacy in their lives. We know that people feel positively about uncovering the mystery of an attractive stranger (e.g., Jourard, 1971; Montgomery, 1986; Vittengl & Holt, 2000), and they get excited about letting an attractive other know themselves. Harry Stack Sullivan (1953) concluded that human beings have a need for intimacy when he observed an early form of intimacy between schoolchildren and their friends. Sullivan judged this middle-childhood increase in intimacy as normative, a judgment that has been born out in later research (e.g., see review by Prager, 1995). The need for intimacy, then, grows and matures with the child as he or she develops.

There seems to be a drive in people to know others and to be known, even if this drive is only given expression with one other person as Rubin (1984) found was common for many American men with their wives. Intimacy fosters the hope that it is possible to know another fully. Maintaining at least one intimate relationship is part of being human.

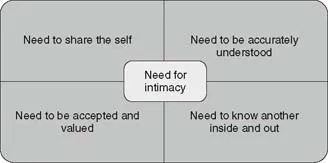

As I have studied intimacy over the years, I have identified four interrelated needs that together compose the need for intimacy (see Figure 1.2). The first is the need to share ourselves with our partners. Through self-disclosure, through nudity and sexual contact, through holding, touching, and kissing, through living in close quarters, and through building lives together, we share our most private selves with our intimate partners. When the other is unavailable, we feel sad and become aware of our unmet needs.

Second, the need for intimacy is a need for another person to fully know and understand us as we know and understand ourselves. Research by Laurenceau, Barrett, and Pietromonaco (1998), Lippert and Prager (2001), Sprecher (1987), and Sprecher, Metts, Burleson, Hatfield, and Thompson (1995) shows that our partner's ability to listen sympathetically to our confidences contributes as much to our satisfaction with our relationship as does our partner's disclosing to us. When this need to be known by the other is not met, we feel lonely and misunderstood (Tornstam, 1992).

Figure 1.2 The need for intimacy and its components

Third, the need for intimacy is a need for that same person—the one that knows us and understands us as we understand ourselves—to fully accept us as we are. Couples who crave but do not give each other mutual acceptance behave defensively and express little appreciation for one another. Their arguments drag on as each gives the other endless evidence of how devoted and long-suffering he or she is and how unfair the other's accusations and criticisms are. These arguments reflect partners' yearnings to be accepted (and appreciated) for who they are and what they do (Jacobson & Christensen, 1996; Jourard, 1971; Reis, 2006; Reis & Shaver, 1988).

Fourth, the need for intimacy is a need to know another person, inside and out, and love that person. Intimate partners want to listen to each other's disclosures as much as they want their own to be heard (Sprecher, 1987). When our partners do not disclose to us, many of us can feel left out of our partner's life.

In sum, intimate relationships fulfill a fundamental psychological need in human beings. The absence of intimacy results in the state of psychological neediness that is loneliness. Most people will continue to yearn for or seek out intimate relationships despite disappointments, hurts, and losses from previous relationships.

Intimacy Dilemmas

The inherent rewards and risks of intimate relating can be usefully grouped into three overarching dilemmas that encompass the challenges of intimacy. For the purposes of this book, an intimacy dilemma is a conflict between two intimacy-related values or motives. These may be mutually exclusive in the sense that one cannot be wholly realized without jeopardizing the other or one may activate intimacy-related risks. Intimacy dilemmas can be internal to the individual or can play out as conflicts between partners. The three intimacy dilemmas are best understood when we recognize intimacy as a simultaneously rewarding and anxiety-provoking aspect of couple relationships. It is these three intimacy dilemmas that organize intimacy-related problems and their treatments in this book.

Relationship partners (and individuals) can respond to intimacy dilemmas adaptively, in ways that sustain satisfactory relationships. Often, however, people who present intimacy problems to couple therapists will be responding in such a way as to disrupt their relationship. They may even avoid initiating or sustaining intimate relationships altogether because they are overwhelmed by the risks of intimacy.

Each of the three intimacy dilemmas occurs because the rewards of intimacy are associated with emotional risks. The next few sections of this chapter explain each of the three intimacy dilemmas and its associated rewards and risks.

Intimacy Dilemma #1: Joy versus Protection from Hurt

Intimacy fulfills needs and offers compelling rewards yet, at the same time, makes us more vulnerable to hurt and loss. Intimate access and subsequent knowledge of another person's self provides us with joy and comfort and alleviates our very human existential loneliness (May,1969; Sartre, 1956; Tillich, 1952). Intimacy's first built-in challenge is to balance the rewards of intimacy with the need to avoid being too vulnerable to hurt or shame, to feel psychologically safe.

Joy versus protection from hurt is intimacy's core dilemma. We confront Dilemma #1 because when we seek intimate contact, we must be willing to risk being hurt or abandoned. Dilemma #1 arises because intimate relating satisfies deep and abiding human psychological needs, but intimate partners are not perfectly reliable sources for fulfilling those needs. Rather, as noted by Cordova, Gee, and Warren (2005), our partners will eventually have an off-day and will respond insensitively or even cruelly to us when we are vulnerable. Those of us who sustain intimate relationships must be able to tolerate these disappointments and still approach our partners again for more intimate contact.

Intimacy's core dilemma comes from the following sources of joy and comfort and their associated psychological risks.

1. Freedom to take off one's public mask. People relax when they are with someone they know very well; knowing and being known gives us permission to drop our public roles and personas. When we drop our vigilance, we allow our private selves to be seen. We can breathe more easily.

Associated risk: Exposing our private selves to criticism, attack, or belittlement. Because our partner has access to ordinarily hidden parts of ourselves, criticism or belittlement from an intimate partner can take on a veneer of brutal truth and can be especially destructive to self-esteem and confidence.

Associated risk: Shaming the self. Even if our partners are supportive, we may ourselves feel shame when we reveal certain personal, private aspects of ourselves that we do not accept in ourselves.

Associated risk: Abandonment. When they get to know what we're really like, our partners may decide they don't want us and leave the relationship.

2. Joys are more joyful when shared. Intimacy brings excitement into a relationship (Aron, Norman, Aron, & ...