- 140 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

How to Write Critical Essays

About this book

This invaluable book offers the student of literature detailed advice on the entire process of critical essay writing, from first facing the question right through to producing a fair copy for final submission to the teacher.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Literary Criticism1 Facing the question

This chapter will be of most use when you have been given a specific question to answer. But even when you have been asked simply to ‘write an essay on’, you should find help here. Some passages will prove suggestive, as you try to think of issues that may be worth raising. Others will show you how these can then be further defined and developed.

Decode the question systematically

If you just glance at a set question and then immediately start to wonder how you will answer it, you are unlikely to produce an interesting essay, let alone a strictly relevant one. To write interesting criticism you need to read well. That means, among many other things, noticing words, exploring their precise implications, and weighing their usefulness in a particular context. You may as well get in some early practice by analysing your title. There are anyway crushingly self-evident advantages in being sure that you do understand a demand before you put effort into trying to fulfil it.

Faced by any question of substantial length, you should make the first entry in your notes a restatement, in your own words, of what your essay is required to do. To this you should constantly refer throughout the process of assembling material, planning your answer’s structure, and writing the essay. Since the sole aim of this reformulation is to assist your own understanding and memory, you can adopt whatever method seems to you most clarifying. Here is one:

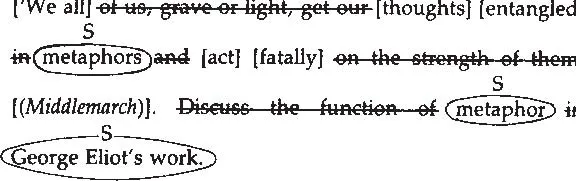

- Write out at the top of the first page of your notes the full question exactly as set.

- Circle the words that seem to you essential.

- Write above each of the words or phrases which you have circled either a capital ‘S’ for ‘Subject’ or a capital ‘A’ for ‘Approach’.

- Place in square brackets any of the still unmarked words which, though not absolutely essential to an understanding of the title’s major demands, seem to you potentially helpful in thinking towards your essay.

- Cross out any word or phrase which, after prudently patient thought, still strikes you as mere grammar or decoration or padding.

Here is an example:

‘We all of us, grave or light, get our thoughts entangled in metaphors and act fatally on the strength of them’ (Middlemarch). Discuss the function of metaphor in George Eliot’s work.

This might become:

The choices I have made here are, of course, debatable.

For instance, some of the words that I have crossed out may strike you as just useful enough to be allowed to survive within square brackets. Presumably, you agree that ‘Discuss’ adds nothing to the demands that any essay-writer would anticipate even before looking at the specific terms of a given question; but what about ‘grave or light’? Might retention of that phrase help you to focus on George Eliot’s tone, its range over different works, or its variability within one? Do metaphors play such a large part in signalling shifts of tone that the alternation of gravity and lightheartedness is a relevant issue? And what about the phrase ‘function of’? Clearly no essay could usefully discuss devices like metaphors without considering the way in which they work, the effect they have upon the reader, and the role that they play relative to other components in a particular text. Nevertheless, you might decide to retain the phrase as a helpful reminder that such issues must apply here as elsewhere.

You may wonder why ‘(Middlemarch)’ has not been circled. The quotation does happen to be from what many regard as George Eliot’s best novel but in fact there is no suggestion that your essay should centre upon that particular work. The title mentions it, in parentheses, only to supply the source of the quotation and thus save those who do not recognize it from wasting time in baffled curiosity. It does, however, seem worth retaining in square brackets. It will remind you to find the relevant passage of the novel and explore the original context. You can predict that the quoted sentence follows or precedes some example of the kind of metaphor which the novel itself regards as deserving comment. Less importantly, the person destined to read your essay has apparently found that passage memorable.

Deciding how to mark a title will not just discipline you into noticing what it demands. It should reassure you, at least in the case of such relatively long questions, that you can already identify issues which deserve further investigation. It thus prevents that sterile panic in which you doubt your ability to think of anything at all to say in your essay. If you tend to suffer from such doubts, make a few further notes immediately after you have reformulated the question. The essential need is to record some of the crucial issues while you have them in mind. Your immediate jottings to counter future writer’s block might in this case include some of the following points, though you could, of course, quite legitimately make wholly different ones.

KEY-TERM QUERIES

‘metaphors’/metaphor:

Quote suggests we ‘all’ think in metaphors but title concentrates demand on metaphor as literary device in G.E.’s written ‘work’: how relate/discriminate these two?

How easy in G.E. to distinguish metaphor from mere simile on one hand and overall symbolism on other?

G.E.’s work:

No guidance on how few or many texts required but ‘work’ broad enough to suggest need of range. Any major differences between ways metaphors are used in, say, Middlemarch, Mill on the Floss & Silas Marner?

‘work’ does not confine essay to novels: use some short stories (Scenes from Clerical Life?)? Check what G.E. wrote in other genres.

How characterize G.E’s use of metaphor? Distinguish from other (contemporary?) novelists?

HELPFUL HINT QUERIES

Middlemarch (quote):

More/less systematically structured on metaphors than other G.E. novels?

Find localized context of quote. What is last metaphor used by text before this generalization and what first after? Do these clarify/alter implications of quote?

‘We all’:

G.E. does keep interrupting story to offer own general observations. Metaphors part of same generalizing process? Or do metaphors bridge gap between concretes of story & abstracts of authorial comment?

How many of text’s crucial metaphors evoke recurring patterns in which all human minds shape their thoughts? How many define more distinctive mental habits of particular characters?

‘thoughts’:

G.E. sometimes called an unusually intellectual novelist. What of text’s own ‘thoughts’ in relation to those supposedly in minds of individual characters? Where/how distinguishable? Text’s more generalized ‘thoughts’ may not just illuminate plot & characters. They may be part of self-portrait by which it constructs itself as a personalized voice. Do they persuade us we’re meeting an inspiringly shrewd person rather than just reading an entertaining book?

‘entangled’:

Word is itself metaphorical. Various connotations: interwoven/ confused/constricted?

What is entangled in what? Characters in their metaphordefined ideas of each other, or of society, or of own past? Many spider’s web metaphors in Middlemarch. Are these different from river images in Mill on the Floss or is being ‘entangled’ much the same as being ‘carried along by current’?

‘act’:

Plot? Are main narrative events described by frequent or powerful use of metaphor?

Where does G.E. offer more specific demonstrations that characters do think in metaphors and act accordingly? Could ‘act’ be a pun? We act upon metaphors in our heads as helplessly as actors conform to lines of scripts? (incidentally, are some G.E. scenes theatrical & is the staginess of some dialogues caused by characters having to pronounce suspiciously wellturned metaphors?)

‘fatally’:

Usefully equivocal?

(a) Some G.E. metaphors do suggest a character’s behaviour is predetermined: we’re all fated to act within limits imposed by our upbringing, our earlier actions & pressures of society.

(b) Other G.E. metaphors expand to tragic resolutions of whole plots which prove literally fatal for major characters. Metaphorical river flowing through Mill on Floss grows to drowning flood (literal & symbolic) of last pages in which hero & heroine die. (Incidentally, is Tom the only hero? What of Stephen? Do metaphors help to signal who matters most?)

These notes may look dauntingly numerous and full, considering that they are meant to represent first thoughts on reviewing the title. Of course, I have not been able to use as economically abbreviated notes as you could safely write when only you need to understand them. Nevertheless, you could obviously not write as much as this unless you already knew some of the texts. Even if you are in that fortunate position when first given a title, you may not want, or feel able, to write so much at this very first stage of the essay-preparation process. Nevertheless, you should always be able to find some issues worth raising at the outset so that, when you embark on your research, you have already jotted down some points that may be worth pursuing.

Notice how often the above examples use question marks. You may later decide—as you read and think more—that some of the problems that first occurred to you should not be discussed in your essay. Even those confirmed as relevant by growing knowledge of the texts will need to be defined far more precisely and fully before you think about composing paragraphs.

Notice too that in a number of cases the issues have emerged through wondering whether any of the question’s terms might have more than one meaning. Investigation of ambiguity can often stir the blank mind into discovering relevant questions.

Terms of approach

You may spot easily enough the keywords in which a title defines your subject-matter but terms prescribing how this is to be approached may prove harder to find. Often they are simply not there. Essay-writing should, after all, exercise your own skills in designing some appropriate style and form in which to define and explore a given literary problem.

Even where a title’s grammar is imperative rather than interrogative, you will usually have to decide for yourself how the topic should be tackled. The title may tell you to ‘Describe’, ‘Discuss’, ‘Debate’, ‘Analyse’, ‘Interpret’, ‘Compare’ or ‘Evaluate’. In all these cases, you are still being asked questions: what do you think are the most relevant issues here? what is the most appropriate evidence which needs to be weighed in investigating them? how should that evidence be presented and on what premises should it be evaluated?

When your essay title uses one of the above imperatives, you must not assume that the demands represented by the others can be ignored. Many students are, for instance, misled by titles which tell them merely to ‘Describe’ some feature of a text. They think this sounds a less intellectually strenuous assignment than one which requires them to ‘Discuss’ or ‘Debate’. They may offer a mere recital of facts rather than an argument about their significance. But the text which you are to describe will often be one which your reader already knows intimately. How you approach and assess even its most obvious features may be of interest to your tutor. The mere fact that these features exist will not. Description in a critical essay must initiate and contribute to debate. To ‘Describe’ is in fact to ‘Discuss’. To discuss intelligently is to be specific, to observe details, to identify the various parts which together determine a work’s overall impact. So you must ‘Analyse’ even where the title’s imperatives do not explicitly include that demand.

Conversely, your being told merely to ‘Interpret’ a play or a novel would still require you to analyse the episodes into which it structures its story, the patterns by which it groups its personages, the distinct idioms through which it identifies their speech patterns and the recurring terms and images which compel all the characters to share its recognizably unified discourse. Interpretation must, of course, expose the ethical, religious or political value systems which a text implicitly reinforces or subverts. Yet these exist only in the architecture of its form and in the building materials of its language. What Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, for instance, is encouraging us to believe cannot be shown by a superficial summary of its plot. Such a summary might be almost identical with that of the original prose version of the story which Shakespeare found in North’s translation of Plutarch.

Where Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar does subtly deviate from its source, it suppresses some of the basic narrative’s latent implications and foregrounds others. So interpretation of just how a particular work seeks to manipulate our definitions of what is true or desirable may also require you to make comparisons. You can hardly have sufficient sense of direction to know where one text is pushing you if your map of literature has no landmarks, and includes no texts which outline some alternative path. Thus, even where an essay title does not explicitly require you to approach one set text by reference to another, you are almost certain to find comparisons useful.

‘Compare’—even where it is not immediately followed by ‘and contrast’—does not mean that you should simply find the common ground between two texts. You must look for dissimilarities as well as similarities. The more shrewdly discriminating your reading of both texts has been, the more your comparison will reveal points at which there is a difference of degree, if not of kind.

Nevertheless, you must wonder what the relatively few works which are regarded as literature do have in common. Your essay is bound to imply some theory as to why these should be studied and what distinguishes them from the vast majority of printed texts.

Student essays sometimes suggest that literature is composed of fictional and imaginative texts, and excludes those which aim to be directly factual or polemical. An English Literature syllabus, however, may include Shakespeare’s plays about political history and Donne’s sermons while excluding those often highly imaginative works which most of your fellow citizens prefer to read: science fiction, for instance, or pornography or historical romances or spy stories.

Alternatively, the focus of your essay may imply that the works which can be discussed profitably in critical prose share an alertness to language; that we can recognize a literary work because it appears at least as interested in the style through which it speaks as in the meaning which it conveys. Yet many of the texts which criticism scornfully ignores—the lyrics of popular songs, advertising slogans, journalistic essays—often play games with words and draw as much attention to signifier as to signified. There is now vigorous controversy as to which of the many available rationales—if any—does stand up to rational examination. Recognize the view which each critical method implicitly supports, and choose accordingly.

‘Evaluate’ may also be already implicit in each of the other imperatives which tend to recur in essay titles. Description without any sense of priorities would be shapeless and neverending. Discussion must be based on some sense of what matters. Analysis may involve a search for the significant among the relatively trivial. Interpretation of a text, and even more obviously comparison of it with another, tends to work— however tentatively—towards some judgement as to the relative importance of what it has to say and the degree of skill with which it says it.

Conversely, evaluative judgements only become criticism when they are grounded upon accurate description of the work which is being praised or condemned. If such judgements are to be sufficiently precise to be clear and sufficiently well supported to be convincing, they must be seen to derive from observant analysis of the work’s components. They must also show sufficient knowledge of other texts to demonstrate by comparison exactly what about this one seems to you relatively impressive or unimpressive. So, too, they must be based on an energetic curiosity about the overall ideological pressure which a text exerts as the cumulative result of its more localized effects. You cannot decide whether to admire a text as an illuminating resource or to condemn it as a mystifying obstruction until you have worked out what ways of thinking it is trying to expand or contain. To evaluate, you must interpret.

These interrelated concepts of evaluation and interpretation are, as the next section explains, more intriguingly problematical than some critics acknowledge.

Some problems of value and meaning

Can the values of a literary work be equally accessible to all its readers? Is a given meaning which interpretative criticism extracts likely to seem as meaningful to one reader as to another, and to remain unaffected by any difference in their respective situations? To take an admittedly extreme example, could a book about slavery—whether it supported or opposed that system—make such-equally convincing sense to both slaves and slave-owners that they would be able to agree on just how good a text it was?

At least in those days when there was still major controversy over whether the slave trade should be eliminated, criticism ought presumably to have anticipated quite different responses to the same text. You might protest, however, that even then there were few slave-owners, and still fewer slaves, among those authors who contributed to the debate; or among the contemporary reviewers who evaluated their works; or among the readers for whom both authors and reviewers wrote. Literature at that time, you might argue, was in fact produced, processed and consumed by a class which had little direct experience of the business world that made its leisure possible. If that were your contention, you might usefully wonder about the relevance of literary values if they can be created, at least in some periods, by those far removed from society’s key-situations.

The notion of an isolated and relatively ignorant circle of writers and readers would anyway need investigating. Jane Austen was well enough informed about the origins of wealth in her own circle to write Mansfield Park, in which Sir Thomas Bertram has to be absent from his Englis...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Introduction

- 1 Facing the question

- 2 Researching an answer

- 3 Planning an argument

- 4 Making a detailed case

- 5 Style

- 6 Presentation

- 7 Postscript on pleasure

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access How to Write Critical Essays by David B. Pirie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.