![]()

Chapter 1

The Multimodal Page: A Systemic Functional Exploration

Christian M. I. M. Matthiessen

Macquarie University

Multimodality—as it has come to be called—is an inherent feature of all aspects of our lives, as it has been, I believe, throughout human evolution. We can interpret this condition of pervasive multimodality “from above” in terms of the stratal organization of semiotic systems, by reference to the context of culture in which different semiotic systems operate, as suggested by Halliday (1977/2003):

Essentially, language expresses the meanings that inhere in and define the culture—the information that constitutes the social system.

Language shares this function with other social semiotic systems: various forms of art, ritual decor and dress, and the like. Cultural meanings are realized through a great variety of symbolic modes, of which semantics is one; the semantic system is the linguistic mode of meaning. There is no need to insist that it is the “primary” one; I do not know what would be regarded as verifying such an assertion. But in important respects language is unique; particularly in its organization as a three-level coding system, with a lexicogrammar interposed between meaning and expression. It is this more than anything which enables language to serve both as a vehicle and as a metaphor, both maintaining and symbolizing the social system, (p. 83)

By viewing different semiotic systems “from above,” from the vantage point of the context of culture in which they operate, we can see that these semiotic, systems complement one another in the creation of meaning. The descriptive and theoretical challenge is to make explicit how they complement one another—how they are coordinated in the process of making meaning and how their complementary contributions are integrated with one another (explicit in the way one would have to in modeling the generation of multimodal documents, as in Matthiessen et al., 1998). This challenge can only be met by taking account of both the semiotic systems themselves and the context in which they operate.

The view “from above” complements the stratal view “from below.” This is the view of semiosis that is foregrounded when we adopt the term multimodality, drawing attention to the multiplicity of “modalities” within the expression plane through which meanings within the content plane are realized. The same is true of the more technological notion of “multimedia.” Here “modality” has to be explored in terms of both the “channel” (e.g., graphic) and “medium” (e.g., written: printed; see Martin, 1992, pp. 508–516; Thibault, chap. 3, this volume). The expressive potential has been expanded through technological advances in both hardware (e.g., from analogue to digital) and software (e.g., new formats, techniques of compression, and standards of representation). The breakthroughs seem to have been driven “from below”: they have, in the first instance, been concerned with the lowest level of the expression plane, making it possible to digitize audio-visual patterns of realization in different semiotic systems. These developments have opened up new possibilities within the content plane— possibilities that are now being taken up to different degrees and in different ways, as is shown by Len Unsworth’s (chap. 11, this volume) study of electronically delivered books for children. But there is a sense in which there is, as yet, no widespread awareness outside expert research teams of what it would mean to technologize the content plane to complement the technologization of the expression plane.

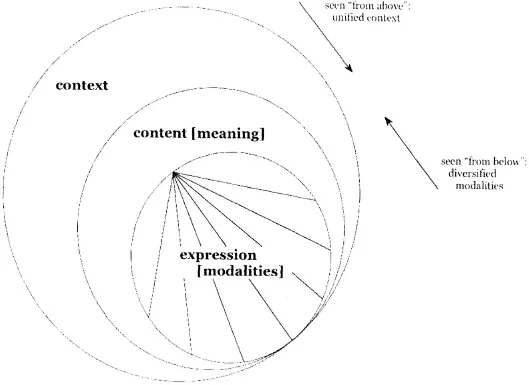

Viewed from below, different semiotic systems thus operate in different realms—that is, in different modalities. But viewed from above, they all operate in the same realm—the realm of meaning. The assumption is thus that differences in modalities within the expression plane decrease as we move into the content plane toward the context, where different semiotic systems are integrated as complementary contributions to the making of meaning in context (see Fig. 1.1). As has become standard in diagrams of this kind, semiotic strata (levels) and planes are ordered from low to high along a dimension running from SE to NW (other orientations being used for dimensions other than that of stratification). The stratal or planar subsystems are represented by co-tangential circles, which increase in size with the stratal move upwards to show that stratal subsystems increase in size, in terms of both systemic potential and extent of units, as we move up the dimension of stratification. The convergence within the content plane of semiotic systems that are realized through different modalities of expression would help explain why it is possible, up to a point, to translate instances (texts, drawings, paintings, ballets, pieces of music, and so on) within one semiotic system into those of another (cf. Matthiessen, 2002, and O’Toole’s, 1994, translation of paintings, sculpture, and architecture into “the language of displayed art”) or to generate instances from a common representation in meaning, as illustrated by the Multex multimodal presentation generation system described in Matthiessen et al. (1998), and why such translations are important in learning because they help learners achieve a more multifaceted and interconnected understanding of the relevant domain of meanings, as shown by Mohan (1986; chap. 9, this volume).

Fig. 1.1. Multimodality: Differences in expression—differences in content?

The semiotic dimension of stratification thus defines two views on multi-modality—the view from above and the view from below; to these we need to add a third view—the view from within the content plane itself.

1. Viewed from above, from the vantage point of context, semiotic systems with different expressive modalities are coordinated and integrated in the creation of meanings in context. All multimodal presentations unfolding in context are like Richard Wagner’s conception of an opera as a Gesamtkunstwerk, where the different contributions are woven together into one unified performance. The primary challenge is how to model this integration within the content plane. The integration can be modeled if this is done systemically (paradigmatically), as seen later in a section (see p. 24). Systemic distinctions shared across different modalities can then be realized in different ways in these different modalities—for example, they may be realized by function structures in language but “rendered” graphically.

2. Viewed from below, from the vantage point of the expression plane, semiotic systems differ precisely because their expressive resources are drawn from different modalities, so when they are modeled explicitly they have to be specified in different ways, as when drawings are “rendered” and music is “synthesized” according to (what we can interpret as) systemic specifications (cf. Matthiessen et al., 1998; Winograd, 1968). The primary challenge here is to determine the extent to which different expressive resources construe qualitatively different content systems.

3. These two views are complemented by a third stratal view. This is the view from within the content plane itself. It is here that the main challenge lies: modeling the meaning-making resources of different semiotic systems in such a way as to provide a synthesis of the thesis that the systems are distinct (derived from below) and the antithesis that the systems function in a unified way (derived from above).

One place to start the exploration of multimodality is with the semiotic system of language since this semiotic system is an inherently multimodal one. This starting point also makes sense in the context of the present book where we are concerned with new directions in considering the multi-modality of the page, computer screen etc.—with a kind of multimodality that typically involves language.

The Inherent Multimodality of Language

The inherent multimodality of language must have evolved out of multimodality in protolanguages as part of human evolution (Matthiessen, 2004) and it develops out of multimodality of protolanguages in the life of human children (Halliday, 1975).

Protolinguistic Multimodality

Protolanguages can, in principle, have the entire body as their expression plane (cf. Thibault’s, 2004, notion of the “signifying body”): they are organized systemically within the content plane into microfunctional meaning potentials (the core ones being regulatory, instrumental, personal, and interactional), and different modes of expression may be brought together within one microfunctional meaning potential or dispersed across more than one such potential. This key property of protolinguistic semiosis can be illustrated by reference to the microfunctional repertoire of chimpanzees (see Table 1.1): Expression modalities include gestures, facial expression, gaze, and vocalization. Interestingly, if we take account of the distinction of the two forms of consciousness identified by Halliday (1992)— action and reflection, we can see that there are strong correlations between meaning and expression as far as the examples given in the table go:

[form of consciousness:] action—regulatory, instrumental

gesture [form of consciousness:] reflection—personal, interactional

various, but: face is involved in all except for ‘excitement,’ which is realized by vocalization; gesture combined with touch is used to express ‘togetherness’

There is thus a strong tendency for a particular mode of expression to go with a particular mode of meaning: The active mode of meaning goes with the active mode of expression—gesture. We can also see that there is a tendency for a natural relationship between specific meanings and specific expressions: Gestures tend to resemble the physical acts that the meanings relate to; for example, the expression realizing I invite you’ is like the act of pulling, and the expression realizing bonding is a mutual stare.

The same picture of expressions in protolanguage has emerged from the study of young human infants (e.g., Halliday, 1975, 1979; Painter, 1984): protolanguages are multimodal in the sense that they employ different modalities within their expression planes; they are not monomodal.1 This multimodality would in fact appear to be one of the keys to the evolution of protolanguage: the multimodality increases the potential for signs that are natural and motivated, and iconic because different modes of expression go with different modes of meaning. Protolinguistic expressions may, of course, be entirely arbitrary; but early expressions often appear to be derivable from a material context, as illustrated by Halliday (1998). For instance, the expression of the instrumental meaning of ‘I want that’ is related to the material act of grabbing the object; this may be compared with the Chimpanzee gesture presented in Table 1.1. This is iconic within the active mode of meaning. But a sigh as a form of expression is equally iconic—within the reflective mode of meaning.

Table 1.1

Protolinguistic Signs Used by Chimpanzees Interpreted Microfunctionally

| Content | Expression |

| Regulatory | ‘I want to be groomed’ [infant to mother] | [gesture:] hand raised in air |

| ‘I refuse’ | [gesture:] shaking head |

| ‘I threaten: keep away(?)’ | [gesture:] waving arm |

| Instrumental | ‘give me’ (begging) | [gesture:] arm stretched out |

| ‘I invite you’ | [gesture:] arm stretched out (as in pulling) |

| Personal | [emotions] | [face, including eyes] |

| excitement (+ identification (?)) | [vocalization:] pant-hoot |

| Interactional | [togetherness] | [touch & gesture, face] |

| Bonding | [face, eyes:] (mutual) stare |

Based on Beaken (1996, p. 51); Hart (1996, pp. 115–117); cf. Kaplan & Rogers (1999, ch. 7) on primates in general and orangutans in particular; Marler (1998).

Later Multimodality: Language and Other Semiotic Systems

As protolanguage evolved into language in the course of phylogenesis and as children make the move from protolanguage to language in the course of ontogenesis, the linguistic multimodality is retained and expanded; ...