The Economic Psychology of Everyday Life

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Economic Psychology of Everyday Life

About This Book

From childhood through to adulthood, retirement and finally death, The Economic Psychology of Everyday Life uniquely explores the economic problems all individuals have to solve across the course of their lives.

Webley, Burgoyne, Lea and Young begin by introducing the concept of economic behaviour and its study. They then examine the main economic issues faced at each life stage, including:

* the impact of advertising on children

* buying a first house and setting up home

* changing family roles and gender-linked inequality

* redundancy and unemployment

* coping on a pension * obituaries, wills and inheritance.

Finally they draw together the commonalties of economic problems across the lifespan, discuss generational and cultural changes in economic behaviour, and examine the significance of other, non-economic constraints, upon individuals.

The Economic Psychology of Everyday Life provides a much-needed comprehensive and accessible guide to economic psychology which will be of great interest to researchers and students.

Frequently asked questions

Information

1

An Introduction to Economic Psychology

What is Economic Behaviour?

We all think we know what economic behaviour is—it is about buying a computer, thinking about investment options, looking at a saving advert and wondering whether we ought to put some money by, choosing a holiday, and evading one’s taxes. But do we really? The behaviours in the opening sentence all seem economic but how about this list: deciding to have children, stealing a car, making a Christmas present, washing one’s clothes. Or walking to work (as opposed to going by car), visiting a friend who lives nearby (as opposed to one who lives further away), giving a friend a lift. By some formal definitions all of these behaviours (and indeed virtually all behaviour) can be seen as economic (Webley and Lea, 1993b). The central concept usually deployed here is scarcity: as Robbins (1932, p. 16) wrote ‘Economics is the science which studies human behaviour as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses’. Economists do not need to confine themselves to those domains we traditionally think of as ‘economic’ (markets, pricing, labour supply) and the intellectual imperialists such as Becker (1976, 1991) have striven hard to extend the scope of economics to explain, among other things, criminal and family behaviour. An alternative view sees economic behaviour simply as those areas that are generally seen as economic (buying, work, saving, etc.), usually as these are activities that go through the market (see Webley and Lea, 1993). But none of these definitions (nor others) take us very far: the pragmatic approach used here is to focus on those problems facing individuals at different points in their life that are best understood (or at least illuminated) from an economic psychology perspective. Thus we do deal with saving but don’t deal with mate choice (although one could).

Approaches to Economic Behaviour

It is possible to regard the study of economic behaviour as just another branch of applied social psychology, where at worst one simply applies standard social psychological theories to economic phenomena (e.g. applying attribution theory to understand people’s explanations for poverty) and at best one develops theories that have more general application (Langer’s, 1975, 1983, ideas of illusion of control and mindlessness might be an example of this). We do not take this view. Our belief is that economic behaviour is best understood by a truly interdisciplinary approach that draws on both economics and psychology (and related disciplines). This is not an easy option: economics and psychology have, in the past, had an uneasy relationship, as the conventions of inference and theory construction are very different. Economists have often shown ‘aggressive uncuriosity’ (Rabin, 1998) towards psychological research and psychologists have often been dismissive of a science based on what seem to them to be absurdly unrealistic assumptions. Nonetheless we believe that a truly interdisciplinary approach will bear fruit in the long term and benefit both parent disciplines. Here we outline some of the alternative perspectives that have been brought to bear in the two disciplines.

Optimality—the economist’s approach

To simplify greatly, economists (or strictly speaking neo-classical economists) begin with the assumption that people are self-interested utility-maximisers—they are selfish and rational. So, faced with an interesting question, say the effect of the introduction of fees on applications for university places, the first step would be to construct a model of the behaviour in question. This would consider the quantifiable benefits of university education (the lifetime increase in earnings as a result of having a degree), the risks (the probability of ending up without a degree), and the costs (for example, of renting student accommodation, of forgone earnings). The model would make a number of simplifying assumptions, for example that universities come in only two types (high- or low-status) or that the choice is between a university in one’s home town or in a distant city. The model would be of the behaviour of units in the system: in our example this could be individuals or households, in other cases it could be firms, regulators or the government. The model is then developed, but always on the assumption that the economic units (of whatever kind) are behaving in their own interests and in the most optimal way. It is important to bear in mind that such models do not usually predict the behaviour of individuals (a particular individual may be altruistic, badly informed or make poor judgements): what they do is to predict average behaviour, or what will happen, all other things being equal. So our model might predict that fees would reduce the number of mature applicants for university places (as the impact on their lifetime earnings of having a degree is less and the cost of taking up a place is higher) or might predict that fees would not reduce the overall number of applications but that students would become more likely to be home-based.

Extension of the optimality approach to the whole lifetime

As we said above, economists try to model behaviours on the assumption that people are trying to maximise utility. This means that when dealing with behaviours such as saving, house-buying and career choice, costs and benefits need to be considered over the very long term. Life-cycle models in economics basically assert that people maximise their utility over their lifetime. A typical model of labour supply, for example, would involve an individual maximising utility (which would be a function of hours worked and leisure); a typical model of saving would involve an individual smoothing consumption and integrating income and consumption streams in order to maximise utility. The following quotation is a very clear example of this approach: ‘An individual maximizes a lifetime utility function whose arguments are an aggregate consumption good, annual hours of leisure during work weeks and annual hours of leisure during nonwork weeks subject to a lifetime wealth constraint’ (Reilly, 1994, p. 463). This may seem very unrealistic as it seems to imply that people have very long time horizons. Put in concrete terms it suggests that one of the factors entering into the decision to take a particular job at age 21 will be the quality of the pension deal on offer. But, again, psychologists’ criticisms of these life-cycle approaches are often misplaced. First of all, these are models of what people do and not how they think: it is possible to behave rationally (to act in the optimum way) without having worked out the likely consequences of different choices (that is, to have engaged in rational thought). Second, life-cycle models in economics are now very complex and sophisticated and take into account different time horizons and time preferences; we shall make some use of those in Chapter 5.

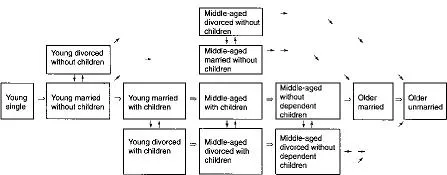

The household life-cycle

The idea of the household life-cycle (at first called the ‘family life-cycle’) was introduced into the study of consumer behaviour by Wells and Gubar in 1966. This approach basically relates spending and other economic behaviour to transitions in the family situation. These might be, for example, the birth of the family’s first child, the departure of the last child from the household or the death of a spouse. The original model excluded non-traditional households (e.g. people who stayed single or parents who never married) and so a number of researchers have suggested modifications to the original scheme. Here we present the Murphy and Staples (1979) version and its associated diagram (Figure 1.1), which is probably the most widely used. This maintains the idea of progression through stages but recognises that there are alternative routes through the life path.

FIGURE 1.1 The modernised household life-cycle model (after Murphy and Staples, 1979)

Although Wilkes is generally positive about the usefulness of the household life-cycle approach, Nyhus (1998) is rather more critical. She points out that twenty years ago Arndt (1979) described the family life-cycle model as ‘one of the most over-quoted and under-researched concepts’ and that this remains a fair description of the current state of affairs. There have been few empirical tests of the model and it seems to add little (in terms of predictive power) to a more straightforward economic life-cycle approach (see for example, Nyhus, 1998; Wagner and Hanna, 1983). Since it is more complex than the latter and has less theoretical grounding, this should give us pause for thought. Nonetheless, from our perspective, it at least provides a framework for thinking about economic choices across the life-cycle.

Developmental psychology

Economists have until fairly recently ignored children (with some honourable exceptions—for example, Harbaugh and Krause, 1999) and have disregarded the value of a developmental approach to understanding behaviour. Broadly speaking, there are two main kinds of theory—one that looks for the origins of economic behaviour in childhood (e.g. Freud, 1908), the other that plots the development of children’s understanding of the economic world (generally through the use of Piagetian stage models, e.g. Berti and Bombi, 1988). Each presents only a partial picture: ‘origin’ theories underestimate the importance of adult experiences and, in particular, the impact of economic constraints and opportunities, whilst Piagetian stage theories overemphasise the significance of adjusting to the adult economic world and minimise the importance of the child’s own behaviour. Both have tended to regard particular ways of thinking and behaving as natural and inevitable, as opposed to being the result of historical and cultural processes.

Expressive/communicative

Social scientists who have focused on the social context of economic behaviour have given us a rather different perspective. Perhaps the first to do so was Veblen (1899), who introduced the idea of conspicuous consumption, the notion that rich people buy expensive goods just because they are expensive in order to signal their wealth and class. This suggests that we should try to understand the goods people buy and exchange as a system of communication, which is the approach taken by Douglas and Isherwood (1996). As they say, ‘The most general objective of the consumer can only be to construct an intelligent universe with the goods he chooses’ (Douglas an...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1: An Introduction to Economic Psychology

- 2: The Early Years—The Economic Problems of Childhood

- 3: Becoming an Economic Adult

- 4: Economic Behaviour In the Family

- 5: Economic Behaviour In Maturity

- 6: The Golden Years? Economic Behaviour In Retirement

- 7: Afterword

- References