This is a test

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This is the first history of Stockholm's development from the city's unique seventeenth-century redevelopment and extension to the postmodern, postindustrial trends of today. While the city's planners borrowed the ideas from abroad at certain periods, they provided the lead for the rest of the world at others. For much of the mid-twentieth century Stockholm was the model for Europe and elsewhere. Written by an acknowledged authority on the city and Swedish architecture and planning generally, with a wide range of illustrations, this book provides a much needed explanation of one of Europe's great cities.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Stockholm by Thomas Hall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Medieval Stockholm: A Planned City?

In 1952 Stockholm celebrated its seven hundredth anniversary with great ceremony. What historical basis was there for this event? When and how did Stockholm really come into being? Was the town the result of a conscious act of foundation in 1253, built to a predetermined plan? Or did it grow up spontaneously with no prior planning? If the former is true, what town was Stockholm modelled on and whose idea was it? In the latter case, what factors governed the street grid and the block divisions?

These seemingly simple questions ought to be capable of finding straight answers. The incompleteness and complexity of the source material, however, makes it impossible to arrive at any clarity, and the questions have been answered in various ways. There are therefore good grounds for resuming the discussion of the problems concerning the origin of Stockholm.

Two main actors should be presented in advance: Earl Birger (died 1266), and his son Magnus (reigned 1275–1290), who is usually given the epithet ‘Barn-Lock’ (Ladulås) because he is believed to have prohibited the nobles from forcibly taking quarters with the peasants and thus plundering their barns. The title Earl (Swedish jarl) was the highest office in the kingdom, corresponding roughly to the Frankish major domus. Birger did not become king himself but managed to establish a royal dynasty, and his sons Valdemar and Magnus became kings.

The Genesis of Stockholm—The Prior History

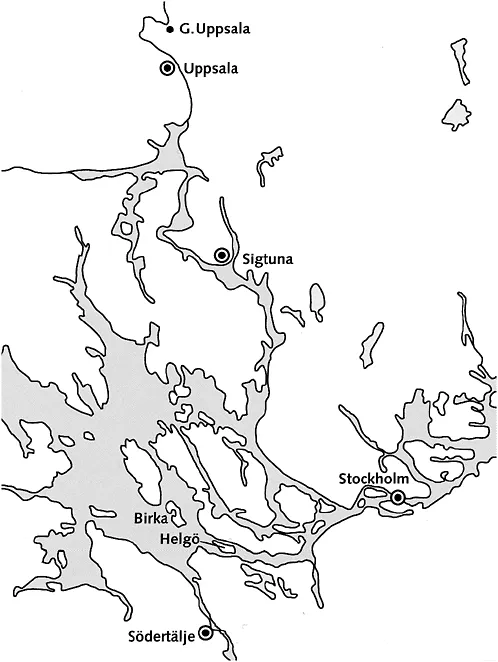

The first place in the Mälaren region for which the designation ‘town’ can be considered is Birka. This conurbation arose in the late eighth century, located on the island of Björkö about 25 kilometres west of today’s Stockholm.

Around the built-up area of Birka—the area known as the Black Earth—there are large cemeteries which have yielded very rich finds. They seem to show that Birka was a trading site where ‘consumer goods’ from Western Europe were sold to customers in central Sweden who had acquired their purchasing power through trading and raids in the east.

Birka seems to have been abandoned around 975. Not much later, Sigtuna makes its first appearance in history (see Hall and Dunér, 1997, pp. 62 et seq.). For Sigtuna we have a diverse body of source material—apart from traditional archaeological finds there are also coins minted on the site, runic stones, and scattered written data. In addition the actual physical structure is preserved. The present-day main street, Stora Gatan, follows basically the same course as it did in the eleventh century, and of the medieval buildings one church remains intact today (St Mary’s), and two (St Olof’s and St Peter’s) are imposing ruins.

Birka and Sigtuna were single, independent settlements. When did the Mälaren region acquire a system of towns in the strict sense? A number of trading sites probably functioned as central places early on, but it is likely that it was not until some time into the thirteenth century that—with the exception of Sigtuna—they attained such a density and judicial status that the term ‘town’ is possible. It can scarcely be questioned that stimulus from German merchants was of crucial significance in this process, or that there was a close link with the change in iron ore mining from a peasant sideline to ‘industrial’ forms of production in the second half of the thirteenth century. The latter half of the thirteenth century is also the period when the integration of Finland in the Swedish kingdom began, with ‘crusades’ and the foundation of fortified sites. The centre of gravity in the emerging Swedish realm was thus shifted eastwards, and the island that would become Stadsholmen found itself in an increasingly central location, in the middle of the Swedish kingdom instead of, as before, on the periphery. The stage was set for the entrance of Stockholm.

Fig. 1.1. Early trading centres and proto-urban places in the eastern Mälaren region.

It is tempting to regard Birka, Sigtuna, and Stockholm as a continuous sequence of towns, even though they represent three different types of medieval town. Birka was a boom town, one of Northern Europe’s most significant centres in the ninth century, but without the judicial status or the permanence one associates with the term ‘town’. Sigtuna was an open trading place, with coining, considerable mercantile activity, and ecclesiastical institutions, but probably without fortifications or municipal bodies. Stockholm, on the other hand, seems to have been a town in the continental sense of the word as early as the end of the thirteenth century. To use a classical definition formulated by the famous Belgian historian Henri Pirenne (1939), it was ‘a community which, enclosed by a town wall, lived by trade and craft, and constituted a juridical person with municipal bodies and its own laws and administration of justice’.

The Written Sources

Erik’s Chronicle

The foundation of Stockholm is treated in two medieval works, the more important of which is known as Erik’s Chronicle, probably composed in the 1330s. The author provides a detailed account in rhyme of the background and origin of the town.

Sweden, according to the anonymous chronicler, suffered serious damage as a result of raiders from the east. Among other things, Sigtuna was burned down.

- This danger was diminished then

By Birger the Earl, wisest of men.

Stockholm town he had built there,

With solid skill and ample care,

A castle fine and goodly town,

And all was done as he laid down.

This is the lock to close the lake,

No more to fear for the Karelians’ sake.

The Documentary Evidence

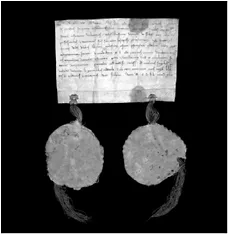

The first documents attesting to the name ‘Stockholm’ are two charters by Earl Birger, signed in Stockholm in the summer of 1252 (fig. 1.2). In Diplomatarium suecanum, a series of publications containing Sweden’s medieval documents, or diplomas as they are called, there are in total about forty items from the period 1252–1289 dated in Stockholm or dealing with matters in the town, all written in Latin (the abbreviation DS is used below to refer to documents in Diplomatarium suecanum). Almost half of them have nothing to do with Stockholm other than that they were signed and dated there. This applies to all the documents written before 1275. After 1278, documents dealing with matters in the town dominate. They mainly consist of the long series of donation charters written by Magnus Barn-Lock.

Fig. 1.2. This charter promising protection to the monastery of Fogdö (DS 390), issued by Earl Birger and King Valdemar in July 1252, contains the oldest extant record of the name of Stockholm. (Source: National Archives, Stockholm)

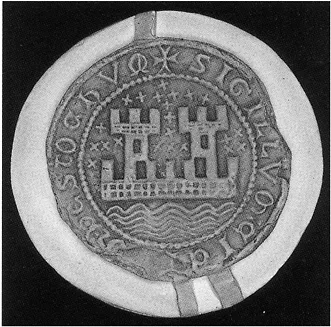

The first document indicating the occurrence of an urban community is a will from 1275 with bequests to a number of ecclesiastical institutions, including the Franciscan (Greyfriars’) friary in Stockholm (DS 865), and a will from the following year mentions the church of St Nicholas (the Great Church or Storkyrkan) for the first time (DS 695). In 1281 we find in a bill of sale, also for the first time, the name of a burgher of Stockholm, Herman Thyring (DS 727). In the same document there is also a mention of ‘the seal of the town’ (see fig. 1.3). In the following year the Stockholm burgher Thideman Friis received a gift from Magnus Barn-Lock in return for his services (DS 757).

In 1285 Magnus began his series of legacies and donations to monastic houses in Stockholm by bequeathing a number of gifts to ‘the Greyfriars in Stockholm, among whom we have chosen to be buried, which no one may prevent on pain of banishment, all the more since it has been granted in a letter by our papal lord’. It is striking how central a place the friary occupies in the will (DS 802). During the latter half of the decade, the monasteries of Stockholm also received a series of bequests from other people (DS 910, 911, 918, 941, 949, 976, 981). In a charter from 1288 (DS 978) the wall around Stockholm is mentioned for the first time. This first decade in the history of Stockholm, as we can follow it in the documents, ends on a consistent note with Prior Laurentius’s letter to the pope in 1289, declaring that Stockholm ‘in just a few years has become more populous than any other town in our country’ (DS 989). In this letter we get the first hint of a vigorous urban pulse in Stockholm.

Fig. 1.3. Stockholm’s oldest known seal in an impression from 1296. It has been said to indicate that the Three Crowns tower was not the only free-standing tower in Stockholm and that there was another to guard the narrows at the south tip of the island. It is doubtful, however, whether the seal can be interpreted as a topographical representation.

The Origin of Stockholm—The Historians’ Views

The Defensive Tower

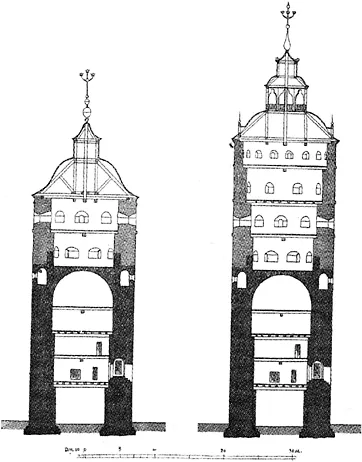

The old castle in Stockholm, when demolished after the great fire of 1697, was not one uniform building but a conglomerate of parts from different periods, including a tower topped by three crowns, which gave the name both to the castle and later to the Swedish national ice-hockey team. The Three Crowns tower is documented in numerous pictures, and also in a survey plan drawn by the architect Jean de la Vallée. It was approximately 25 metres tall and 15 metres in diameter before King Gustav Vasa had it extended in 1544 (fig. 1.4). When was this tower first built? Most scholars believe that it was older than the rest of the stronghold, and that it was originally a free-standing tower of the type known as a kastal, probably constructed during the long and relatively stable reign of Knut Eriksson (c. 1167–1196), or no later than the start of the thirteenth century.

The Town

The questions when, how, and why the town of Stockholm arose have been discussed for almost as long as history has been written in Sweden, that is to say, at least since the sixteenth century.

Fig. 1.4. Reconstructed sections through the Three Crowns tower after vertical extensions in 1544 and 1588. The tower was probably the first large building on Stadsholmen. (Source: Olsson, 1940)

The first twentieth-century scholars who investigated the origin of Stockholm—Nils Östman, L. M. Bååth, and Ragnar Josephson—assumed that there was a settlement on Stadsholmen before Earl Birger. Östman believed that it had come into existence even ‘before the year 1000’, but both Östman and Josephson thought that a radical regularization of the town plan had been undertaken during Earl Birger’s time. Adolf Schück (1926), in contrast, claimed in his work on the origin and growth of Swedish towns, that had there been a settlement on Stadsholmen before Earl Birger then it was not on a large enough scale to warrant description as a town. As regards the origin of Stockholm, Schück was relatively summary. He did not accept without reservation the account in Erik’s Chronicle, but stressed instead the growth of mining as ‘one of the primary reasons for the rapid development of Stockholm in the latter half of the thirteenth century’.

In 1933 Gunnar Bolin presented a doctoral study about the origin of Stockholm. His conclusion was that Earl Birger, following ‘what was then a fashionable continental pattern, consciously founded the town of Stockholm as the first Swedish urban foundation of this kind’. The next milestone in research on Stockholm’s origin was Nils Ahnlund’s major work Stockholms historia före Gustav Vasa, published to mark the seven hundredth anniversary of the city in 1952. Ahnlund was in no doubt that Earl Birger was ‘the builder of the town’. Kjell Kumlien (1953) believed, on the one hand, that ‘Stockholm as a national stronghold and trading place arose at the end of the twelfth century’, and on the other hand that it did not really flourish as a commercial town until a decade or two after Earl Birger, ‘when the first “industrialized” phase of our mining had its—relatively late—beginning’. Hans Hansson (1956), who only dealt cursorily with the question of the foundation, thought that Earl Birger’s documented visit in the summer of 1252 could have been ‘occasioned by the foundation of the town’. In his opinion there are ‘no grounds for doubting the statement in Erik’s Chronicle that the earl had the town and the castle built, and that he personally took part in the planning’. Gerhard Eimer (1967) likewise viewed ‘the staking out of Stockholm’ as ‘a swift action during the 1250s, with the state as the driving force’.

Thus the majority of the twentieth-century scholars who studied the origin of Stockholm have interpreted the town as having been planned and built by Earl Birger. This was the state of research in 1972 when I published my dissertation Stockholms förutsättningar och uppkomst. In it I claimed that an analysis that considers both the town plan and the documentary evidence clearly indicates that Stockholm was not founded at the start of the 1250s but grew up gradually during the second half of the century. I shall return later to the arguments for this interpretation.

Since my dissertation, nothing has come to light that has had any crucial impact on the questions and results presented there. In 1981 the ‘Medieval Town’, a research project covering all medieval Swedish cities, published a report on Stockholm (no. 17). The emphasis was on compiling the evidence, while the different opinions about the origin of the town are only considered briefly, and no real stance is taken as to which is correct. Similarly, Staffan Högberg’s Stockholms historia, published in the same year, does not tackle the issue of the origin of Stockholm.

Norrström

The large-scale excavation on Helgeandsholmen, 1978–1980, published in the volume Helgeandsholmen, 1000 år i Stockholms ström (Dahlbäck, 1982), gave no new material about the origin of the urban community, but it did provide information about the fortifications that once existed in Norrström, the water between the island of Stadsholmen and the mainland to the north (see pp. 11 ff.). The editor of the report, Göran Dahlbäck, has also published a book on the medieval town, I medeltidens Stockholm (1988). Here the problem of the origin of the town is mentioned only in passing, but as I understand it, Dahlbäck’s views mainly agree with the interpretation in my dissertation.

The most recent major work on the origin of Stockholm is Anders Ödman’s doctoral dissertation Stockholms tre borgar (‘Stockholm’s Three Castles’, 1987), of which Earl Birger’s fortress is the last, while the first two forts were in Norrström. He seems to think that the plateau of Stadsholmen was in principle empty until the 1250s, when Earl Birger began to build the Three Crowns tower as the first step in the construction of a castle. Work then continued on the rest of the stronghold. The assumption that Stockholm grew quickly in the latter part of the thirteenth century agrees with my interpretation.

Topography and Street Grid

The central part of Stadsholmen consists of a triangular plateau with its base towards the north (fig. 1.5). On the eastern side the plateau is bounded by Baggensgatan and Bollhusgränd, which at certain points are almost 10 metres above Österlånggatan. The difference in height between Baggensgatan and Själagårdsgatan, on the other hand, is insignificant. On the western side the boundary of the plateau is not as clearly marked. The difference in level between Prästgatan and Västerlånggatan is generally less than 5 metres, while Skomakargatan is between 1 and 3 metres above Prästgatan. Svartmangatan is at a slightly higher level than Skomakargatan, and for most of its course it is slightly lower than Själagårdsgatan.

The blocks between Trångsund and Skomakargatan on the west side and Bollhusgränd and Baggensgatan on the east side are thus a relatively flat area, sloping gently to the west, at 13 to 15.5 metres above today’s sea level. The original shape of the plateau cannot be determined exactly, but human alterations of the topography have probably been of relatively limited scope, apart from the site of the palace, where the original ground level, according to the established opinion, was 6 to 7 metres above today’s inner courtyard, although this has been questioned (Ödman, 1987).

Outside the plateau, however, the topography has been completely transformed as a result of land uplift and filling. The present level of the ‘long streets’, Öster- and Västerlånggatan, is 2 metres or more above the original slope of the shore. Th...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Medieval Stockholm: A Planned City?

- Chapter 2 The Capital of a Great Power

- Chapter 3 The Lindhagen Plan: A Vision Realized

- Chapter 4 The Completion of the Inner City, 1900–1940

- Chapter 5 The Coming of the Outer City: From Enskede to Skarpnäck

- Chapter 6 ‘A Display Window for Sweden’: The Rise and Fall of the City-Centre Reconstruction

- Chapter 7 Concluding Reflections: A Look Back at Aspects of Stockholm’s Development

- Stockholm in the New Millennium

- Controversial Metropolitan Icons: Tall Buildings in the Stockholm Cityscape by

- Bibliography