This is a test

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First full-length study of Loos's texts available in English Based on original research and makes extensive use of primary sources Offers a genuinely inter-disciplinary approach

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Fashioning Vienna by Janet Stewart in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Investigating and excavating

Had Loos lived in ancient times, he would probably have become an itinerant philosopher delivering his pearls of wisdom in the town square. In the middle ages, he would perhaps have become a preaching mendicant, moving from place to place.(Friedell [1920/21] 1985:77)

The storyteller: he is the man who could let the wick of his life be consumed completely by the gentle flame of his story.(Benjamin 1992:107)

Loos’s textual work spans a wide range of genres including the feuilleton, the lecture, the poster, the journal, the book and others. Commencing with the collections of Loos’s texts published in book form, then looking at archival materials, essays and lectures, this chapter focuses on the intertextuality of his writings. The investigation is organised around the ‘architextuality’, and the ‘paratextuality’ of his texts and lectures, where ‘architextuality’ (Genette 1992) describes the gestures towards genre demarcation contained in the set of categories which determine the nature of a text, and ‘paratextuality’ (Genette 1997) denotes the relationship between the body of a text and its titles, illustrations, dedications, mottoes, prefaces and so on. The conduct of such an analysis casts the researcher hi the role of Collector, performing an excavation of Loos’s texts in book form, wrenching them out of this context—the context in which we are most used to confronting them at present—and collecting them in new constellations. These new constellations consist of an analysis of the essay as form and the lecture as form, together with an exploration of the context of the urban locations (in the case of the lectures), and the newspaper and journals (in the case of the essays) in which they first appeared.

Architextuality

Published collections of Loos’s texts

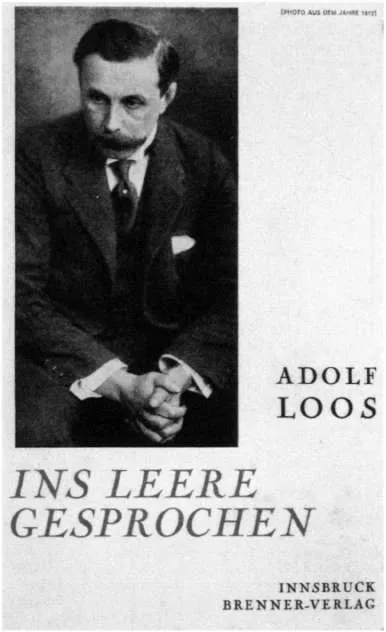

In their original form, Loos’s texts appeared either as newspaper or journal articles, or were delivered as lectures. However, many of his writings were subsequently collected and published in book form during his lifetime. Others were published posthumously. The first edition of Loos’s essays to appear, published by Georges Crés et Cie (Paris-Zurich) in 1921, was entitled Ins leere gesprochen. It was based on a selection of early essays (1897–1900), including the series of articles which Loos wrote for the Neue Freie Presse, the best-known Viennese daily paper at the turn of the century, on the occasion of the Imperial Jubilee Exhibition (1898), celebrating fifty years of Kaiser Franz Jose’s reign. According to Loos’s (1921:5) preface to this edition, his original intention had been to publish this series of articles in book form immediately after the exhibition.1 However, his publisher backed out, deeming the articles no longer relevant, and Loos made no further attempts to secure publication. The 1921 edition, as his preface makes clear, was made possible by the work of his architecture students in seeking out and collecting his early articles some twenty years after their original publication. A first attempt to publish the articles with the Kurt-Wolff Verlag foundered on Loos’s refusal to edit out personal attacks on Josef Hofftnann. Finally, Georges Crés et Cie agreed to publish the collection, emphasising in their advance notices that no German publisher had been prepared to publish Ins leere gesprochen. There are a number of bibliographical inaccuracies in the collection, which probably occurred because of the nature of its genesis.2

A second, reworked edition of Ins leere gesprochen was published in 1931 by the Brenner-Verlag in Innsbruck, edited by Franz Glück. The most obvious differences between the 1921 and 1931 editions of Ins leere gesprochen lie in content and form. In the 1931 edition, ‘A review of applied arts II’ and ‘The winter exhibitions in the Austrian Museum’ were omitted, while ‘Potemkin City’ was added. The order in which the individual articles appeared was also altered; whereas the 1921 edition is divided into six sections, according to the newspaper or journal in which the texts were first published, the 1931 edition has only two sections. The first contains the texts which were published on the occasion of the Imperial Jubilee Exhibition in 1898, and the second, the remaining texts. The 1931 edition also has a new preface, which comprises a shortened version of the preface and the afterword from the 1921 edition, and a set of notes written by Loos (1931a:221–2). Other editorial modifications made by Glück include variations in content of the individual articles, editing out sections of text, and orthographic and grammatical changes (Eckel 1995).

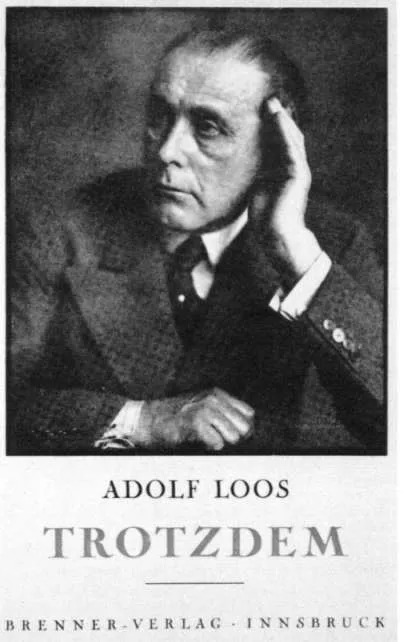

The 1931 edition of Ins leere gesprochen appeared in the wake of a second collection of Loos’s texts, entitled Trotzdem,3 which was also published by the Brenner-Verlag, coinciding with the publication of the first monograph on Loos (Kulka 1931).4 While the bibliographical inaccuracies in Ins leere gesprochen were relatively few, there are many more problems with Trotzdem, which is unsurprising, given the much longer period that the articles in this collection span (1900–30).5 Since 1931, two further editions of Ins leere gesprochen and Trotzdem have been published. In 1962, they appeared together as the first volume of Adolf Loos: Sämtliche Schriften edited by Franz Glück,6 while in 1981 (Ins leere gesprochen) and 1982 (Trotzdem) they were published by the Georg Prachner Verlag, edited by Adolf Opel.7 Although these volumes are the only collections of his essays to appear during his lifetime, they do not include the full extent of Loos’s texts, as Glück’s planned publication of a second volume proves.

In the 1980s, three new collections of Loos’s texts were published, edited by Adolf Opel. The first, entitled Die Potemkin’sche Stadt (Loos 1983), consists of a collection of Loos’s articles found by Opel in archives and primary publications and not included in either Ins leere gesprochen or Trotzdem. The others, Kontroversen (Opel 1985) and Konfrontationen (Opel 1988), contain a few articles by Loos, but the majority of the essays are contemporary articles and newspaper reports about Loos. Subsequently, Opel edited a further collection of Loos’s writings on architecture under the title Über Architektur (Loos 1995), based on the original newspaper and journal publications rather than the versions of the texts which appeared in previous collections.8 Rukschcio has criticised Opel’s editions of Loos’s texts for their lack of accuracy (Weingraber, 1987:10). Eckel (1995:87–9) adds another critical voice, claiming that the publication of Die Potemkin’sche Stadt has caused serious confusion in Loos scholarship, due to the fact that Opel neglected to include accurate bibliographical references for the articles he reproduced. However, despite certain inaccuracies, Opel’s new collections have rediscovered forgotten, hidden or rather inaccessible texts, and therefore represent an important resource for research into Loos’s texts which cannot simply be disregarded. The appearance of any such ‘new’ material plays an integral role in the process of excavating Loos’s cultural critique; it means that the layers of interpretation and reinterpretation must be re-examined.9 Rather than ignoring Opel’s collections, it is necessary to engage with them, meeting the challenge to provide the missing bibliographical material (as far as possible) by tracing the texts reproduced in these collections to the journals and newspapers in which they first appeared.10 The often bitter criticism of Opel’s editions of Trotzdem and Ins leere gesprochen, and of the four new collections of Loos’s writings which he edited, also points to another area worthy of investigation. Taken together with the non-appearance of the second volume of Sämtliche Schriften, the criticism directed at Opel reveals Loos’s texts to be a location of intense disagreement. Nowhere is this dispute more apparent than in the ongoing conflict over the ownership of Loos’s estate.

Figure 1.1 Front cover of the 1931 edition of Ins leere gesprochen

Source: Bildarchiv, ÖNB Vienna.

Source: Bildarchiv, ÖNB Vienna.

‘The messy space of the archive’

Most existing studies of Loos’s work are silent on the subject of the archive and the fate of his estate; an exception to this silence is provided by Colomina (1994). However, her partial account of the Loos estate focuses on the story of his architectural papers and plans, thus suppressing the fate of his personal and literary papers. It was indeed the case, as Colomina (1994:1) asserts, that Loos ordered Heinrich Kulka and Grethe Hentschel to pack up the contents of his office when he left Vienna for Paris in 1922, and to destroy the papers which he had left behind. It was also the case that Kulka and Hentschel did not follow these orders, but kept the papers. However, Colombia’s (1994:1) claim that the collection of papers rescued by Kulka and Hentschel ‘will become the only evidence for generations of scholarship’ draws a veil over the full story of Loos’s estate, failing to address adequately the nature of the documentary sources available to Loos scholars today. There are two major flaws in Colomina’s version: first, her assertion that Loos himself was solely responsible for the removal of traces of his life and work, forcing later researchers into processes of reconstruction, masks the fact that the destruction and loss of documents can often be attributed to scholars and self-appointed guardians of Loos’s inheritance; and second, her comments are only partially applicable to the textual part of his estate.

Figure 1.2 Front cover of the 1931 edition of Trotzdem

Source: Bildarchiv, ÖNB Vienna.

Source: Bildarchiv, ÖNB Vienna.

In 1934, an article announcing Ludwig Münz’s and Franz Glück’s intention to establish a Loos Archive appeared in various newspapers, including the Wiener Zeitung (24 October) and the Prayer Presse (26 October). The article urged anyone owning ‘plans, sketches, photographs, reports, letters and other documents’ or who had immortalised Loos in their memoirs to contact either Münz or Glück. Potential contributors were assured that donations would be united with the materials comprising Loos’s estate with the dual intention of preparing a Loos exhibition and publishing both the architectural and textual sections of his estate. This was, however, not the first attempt to establish a collection of privately owned materials relating to Loos; a similar venture, based on a questionnaire sent out by the Anton Schroll Verlag, served as the foundation for Kulka’s (1931) monograph on Loos.11

These attempts to collect and to order Loos’s papers and texts follow the spirit of the suggestions for dealing with literary estates that appeared in Guidelines for a Ministry of Culture, a pamphlet edited by Loos:12

Letters, manuscripts and papers belonging to Austrian authors must not be allowed to be split up and must be made available to scholars through a state-run agency. An archive is to be set up for documents of literary value. An inventory of manuscript collections in private ownership or in the possession of local authorities is to be drawn up.(Loos 1919c:9)

The sentiment underlying these guidelines is in marked contrast to the fate of the Loos estate, and particularly to the fate of the textual part of his estate. It is evident that as early as 1934 there were plans to publish the previously unpublished articles and papers included in the Loos estate. Over sixty years later, however, these plans have still not been realised. Nor has it been possible to establish a usable and comprehensive archive in which the contents of the Loos estate would be united with donated materials such as letters, manuscripts and others, despite Schachel’s (1982:76) plea that materials in private collections should be brought to the Albertina.

Nevertheless, the Albertina in Vienna does house an ‘Adolf Loos Archive’ (ALA). The basis of this archive is formed by materials which were collected by Ludwig Münz who, according to a declaration written by Elsie Altmann-Loos in 1933,13 was given authority to take care of all the ‘artistic questions relating to Loos’ (Weingraber 1987:7).14 These materials were sold to the Albertina in 1966 and comprised twenty-eight labelled large folders, four unmarked large folders and fourteen smaller folders, as well as plans, drawings, photos and correspondence. In 1968, Rukschcio began sorting, ordering, cataloguing and adding to the collection.15 He completed his work in the archive in 1973, by which time, according to the report which he made to the Austrian Ministry for Science and Research, he had first, ordered the material in the estate into folders containing plans, texts and photos respectively; second, discovered new plans and corrected the dating of architectural works; third, created a photo archive; and fourth, produced a catalogue of Loos’s work (Rukschcio 1973). However, his claim to have achieved a ‘complete collection of Loos’s writings and publicat...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction(s)

- 1 Investigating and excavating

- 2 The Other: national cultural mythologies

- 3 The Self: social difference in Loos’s Vienna

- 4 The display and disguise of difference

- 5 Locating the narrative: the city, its artefacts and its attractions

- Conclusion: the non-contemporaneity of Loos’s critique

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index