A Decade of Forced Entertainment

Created to mark our 10th anniversary A Decade of Forced Entertainment is a speculative history of the company, a collage of fragments of previous works and a meditation on the place and processes of new performance. It was first performed on 3 December 1994: the six of us sat at a pair of long tables facing the audience in the ICA theatre, with a continuous cycle of Hugo Glendinning’s images of the work and of Sheffield (and of a series of specially prepared maps of the UK bearing slogans) on three projection screens behind us.

The programme note described the work as ‘part autobiography, part archive, part historical meditation and part theoretical speculation—a look back on ten years of the company’s work and on ten years of change in the British urban culture from which it has sprung’.

Part One

Hans: Mike, Dolores, tell us a bit about the act.

Mike: Well, we did a thing quite a while ago now, it was a love show and everyone on the stage drank down a love potion that er, sent them all off to sleep and when they all woke up again they were all in love and no one felt sad.

Hans: I see.

Mike: Well, that’s not the kind of work we want to do anymore.

(Some Confusions in the Law about Love, 1989)

Terry: We wanted to look back on the decade 1984–1994—the ten years in which we’ve been making our work, and we knew that this looking back would have to include the things that hadn’t happened as readily as those that had. We had in mind a map of the last ten years—a haunted map—a false map—and yet, in some ways, an accurate map.

And at some point we realised that this map-making, this charting of a time and a landscape, was what our work had often consisted of. A kind of mapping, a kind of temperature-taking.

Tim: 10 years of Forced Entertainment is 10 years finding notes in the street. When we first got to Sheffield we didn’t know anyone—so the first months were very voyeuristic—months spent watching, trying to pick up the patterns of the place. In this time, above all others, we found notes and photographs in the street.

There was a note to a woman at a bus stop—along the lines of ‘I see you every day but will never dare speak to you…’. There was a letter from someone in prison, that had been torn into pieces as small as confetti but which were reassembled by us on the formica-topped table at 388 City Road.

All through the winter we found things. There was a photograph of the ground beside a Mediterranean swimming pool, there was page ripped out of a kid’s cowboy book which had been vandalised so that where it once said ‘Tex gunned the man down…’ it now said ‘Tex bummed the man…’.

There were discarded photographs, there were incomprehensible shopping lists, there was a note I found near the high-rise flats which said ‘DAVE—I HAD TO GET OUT-THE GAS IS CUT OFF AND THE TV HAS GONE BAD-BACK THURSDAY’.

There was a map, showing how to get to the motorway.

Cathy: Working on Nighthawks (1985) we wanted to make a far-away country called America in the Movies—we were determined that nothing in the performance should be recognisably British. So, following this peculiar logic we made regular visits to the Chinese take-away on London Road to collect their old Chinese newspapers, which were thrown around on-stage. For the same show we made trips out to Manor Top Industrial Estate to pick up soda siphons; we caught the bus to Killamarsh to try and find three identical bar stools, we collected obscure liquor bottles from shit night-clubs all over town. Getting to know the city through trying to find a ramshackle collection of props and set.

Unfortunately one day when we were driving a Cornflakes truck hit us doing 93. And I remember thinking how quiet the whole world seemed and still and wondering if you blacked out before you hit the windscreen.

We died in the accident of course. I lost control of my bladder before we hit the Kellogg’s truck so I didn’t mind: my best suit was ruined anyway.

((Let the Water Run its Course) to the Sea that Made the Promise, 1986)

Claire: They drew a map of the country and marked on it the events of the last 10 years—the sites of political and industrial conflict, the ecological disasters, the showbiz marriages and celebrity divorces. On the same map they marked the events of their own lives—the performances they’d given, the towns and cities where they’d stayed, the sites of injuries and fallings in or out of love.

They drew a map of the country and marked on it the events of the previous 300, then 400, then 500 years. They kept on going until the beginnings of geological time. Until the map was scribbled over a thousand times—utterly black.

They knew something strange had happened to time. They drew a map of the country and marked on it events from the rest of the world. On this map the Challenger Space Shuttle had blown up in Manchester 1985. The Union Carbide Bophal Chemical Works which exploded late in 1984 was located in Kent. The siege of the Russian Parliament Building in 1991 had taken place in Liverpool. The Democratic Party’s recent set-backs in the mid-term elections had been most severe in the Isle of Dogs. The 1989 fatwa on Salman Rushdie had been issued from Tunbridge Wells.

After the Kellogg’s truck hit us and killed us we went to the hospital. There we were put in the capable hands of Dr Lyver who had plenty of money.

Seeing as how we were dead they put sort of plastic taps in our arms and drained all the red sort of blood out of us into a sort of bucket. Then they got lots of other blood and pumped it into us through all possible entrances.

This new blood they put in us was stuff they’d collected here and there from other people. The blood it mixed together all these people’s blood and thoughts and everything and this was our biggest problem you see: because the blood moved inside us, changing and turning: one person then another, we dint know who the fuck shit piss we were, we’d say one thing then another, stand up, sit down, the blood moved, we didn’t know.

((Let the Water Run its Course) to the Sea that Made the Promise, 1986)

Tim: We’d like two silences now. First one minute’s silence for Steve Rogers—Steve was editor of Performance magazine in the mid-80s and was very important to us and the whole sector of live art and experimental performance here in the UK by way of energy and criticism and constant encouragement. Steve died, along with his partner Mark, of AIDS-related illnesses in 1988. One minute’s silence please, for Steve and Mark.

And a minute’s silence for Ron Vawter, who died in 1994, also of AIDS-related illnesses. Ron was a performer with The Wooster Group, and his performances, his energy and openness inspired all of us here.

- A: Howl! Howl! Wake it up poor dead person for we are upset and grieving angels.

- B: Oh we are distressed and sorrowful angels!

- A: And we have lamented of all and weighty things.

- B: We have wept on drinking and eternity and of dreams etc.

- A: We have cried for loving and of souls and of death.

- B: But we have never grieved as much as this before.

- A: Wake it up and think all hard of this…If you don’t to get up who will shout and sing songs at the stupid moon?

- B: Who will to live in then your idiot house?

- A: Who will bang its walls and blood and bruise its stairs?

- B: O we are drunk and dependable angels and we can to raise our friends from out the dead.

- A: When we to say of now you will jump and rise and live again.

- A&B: 1.2.3. Now!

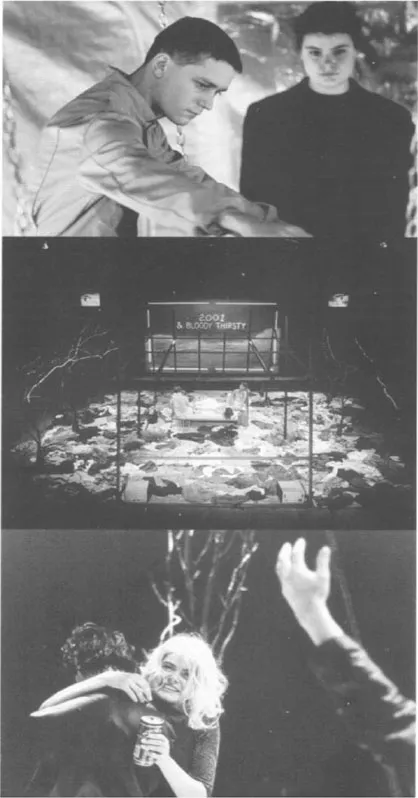

- (200% & Bloody Thirsty, 1988)

Part Two

Terry: We made work for 10 years in a country with a Conservative government. None of us ever voted in a general election that returned anything other than a Conservative government.

As things changed, the maps we made of the country had to be redrawn.

Richard: We noticed big changes to the country but could never date them precisely. When did the streets fill up with beggars? When did the great programmes of building, rebuilding and demolition begin? When exactly did the shopping malls and the 10-screen cinemas arrive? When did our city get its lift shaped like a rocket? From the day these places opened it seemed like they’d always been there.

As time went on we got more and more sure that the work should look thrown together—chaotic, out of control, unintended—so that, perhaps, when it did pull something out of the bag, one simply wasn’t prepared. The chaos of the work was always running to catch up with the chaos and confusion of the times it came out of.

We admired the title of a Cady Nolan sculpture—a pile of aluminium baskets, mace canisters, and back issues of the magazine Guns & Ammo—she called it: Bloody Mess.

We liked that feeling that events on-stage were simply falling into place, that meaning was always an accident, although of course it rarely was.

Claire: Everything they seemed to use was brutal in some way. The materials were heavy steel, often rusted—the structures looked like buildings under construction, or buildings stripped of the walls. They used dirty untreated plywood, cardboard for writing on, cardboard to cover the floor. There was always the unreal beauty of electric light, the shabby mess of polythene and jumble-sale clothes.

In 1989 we made a show, not about Elvis Presley but about an Elvis Presley impersonator in Birmingham, England. We didn’t want anything authentic, we wanted a third-rate copy—we loved that more dearly than anything original.

Robin: They were interested in the margins of life, never the centre. They tried not to talk about the people who made decisions but about those people who were affected by decisions made in other times and other places. They were provincial, by choice and by accident.

Is it true that the more desperate and depressed a city becomes the more exotic the names of its night-clubs and amusement arcades become? They thought so. Through the 80s and into the 90s the city they lived in had a bar called MILLIONAIRES and a casino called BONAPARTES—one night they heard a drunk boasting how he once paid five pounds for a sandwich in BONAPARTES—he thought it was great. They drew a map of the country and marked on it the amusement hall called GOLD RUSH, the discount shop called BARGAIN WORLD.

Terry: Is it true that the only way to see Britain properly is to see it drunk? They thought so. There were drunks in all of the shows, often drunks who were also dead.

Walking in the city they’d use an almost conscious confusion. What were they trying to solve—the latest show or the city itself? Eating pizza after late-night rehearsals they’d see a riotous hen party—a woman dancing on the table and pulling her tights off as she danced. They’d discover a blind man negotiating his way through the tangle of builders’ scaffolding near their rehearsal space on the Wicker—the city’s most notorious has-been street. They’d ask why aren’t these things represented in the show? How could a map of the country include these things? Why isn’t the texture of the show as desperate and gaudy and vital as these things? They laughed when the blind man told them (1) he’d just been to the match and (2) he was utterly pissed.

Tim: Beyond the city itself lay an alternative city too—not the one of nightclubs and blues clubs, but one of craters and broken ground. It seemed that during the Second World War the city lights had been blacked out and a decoy metropolis created in the hills using searchlights and halogen floods. So the hills took the pounding for the city and the Germans bombed the grass, stone and moor land into burning mud. So the city always had its twin—an empty space waiting for them to fill it. Much of the rest of the city was empty anyway. Walking around in 1984 and 1985 you’d never seen so many disused factories and fields of rubble. Often on Sundays, in those days, they’d walk, exploring the city and these empty buildings; places still littered with time sheets and newspapers. Was it in one of these places that they saw the graffiti DOWN WITH CHILDHOOD and RAPE A TART TONIGHT?

The night the rain stopped was wild and cold and full of strange noises and we did magic acts and were scared for each other and ourselves. We practised CLOSING BOTH EYES TIGHT WHILST DRIVING DOWN A ROAD, we practised EXHIBITION OF DUST. We practised HAUNTED GOLF. We worked on YOU’RE GOING HOME IN A FUCKING AMBULANCE.

This is the life that we lived then, in the city, in the chaos and the dark…

(Emanuelle Enchanted, 1992)

Richard: They drew a map of the country and marked on it the locations for a hundred fictional events—here the house in which gangster James Fox goes into hiding in Nick Roeg and Donald Cammell’s film Performance; here the wind-blown meadow from Tarkovsky’s film Mirror; here the crack house from Victor Headley’s novel Yardie; here the Mexican town rebuilt by a film crew as a Wild West town in Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie; here the New Rose Hotel from William Gibson’s story of the same name.

They drew a map of the country and marked it with the street names they’d collected over years, some real, some from fiction, some dreamed up just because they sounded good. They marked on the map ESPERANTO PLACE, OCCUPATION AVENUE, METEORITE STREET and ALPHABET ROAD.

Claire: Was it really in the 80s that the naming of things became so wonderfully and inventively blunt? It seemed like it. They drew a map of the country and marked on it MR BUYRITE. Hi-Fi WORLD and BARGAIN LAND. They even saw a street somewhere called CAR PARK WAY. They marked this street on the map. At the end of this line lies I CAN’T BELIEVE THAT’S NOT BUTTER and a beer called THIS BEER IS THE BEST BEER I’VE EVER DRUNK IN MY WHOLE LIFE I SWEAR TO GOD. After the seductive power of ambiguous images it all comes back to hard sell. They marked on the map a bar they’d seen in Zurich (1988)—THE EVERYTHING A MAN COULD WANT BAR.

They drew a map of the country and marked on it roads named after Scargill, after Mellor and de Sanchez, after Reagan, North and Yeltsin. They marked roads named after Rodney King, after Arnold Schwarzenegger, after the Birmingham Six and the Guilford Four, they marked roads named after Diego Maradonna and Eric Morecambe. They marked a public park named after Nicolae Ceaucescu, and another named after Edwina Currie. They named a public square after the Russian cosmonauts who’d been circling the earth during the coup, unable to return and uncertain of what they’d come back to. They named bridges for deposed presidents, for kids on job-creation schemes and for the glue sniffers who’d graffitied on an abandoned house near where they lived, in big letters, a sign saying DAVE’S GLUE CLUB—EVERYONE WELCOME.

On the map they marked museums for love and drunkenness, museums for rioters, accidents, happenstance and luck.

Richard: On the map they marked the questions from a decade of end of year quizzes.

- In what year did the European Single Market begin?

- Who said and in what year ‘I am Jesus Christ and I announce the end of the world’?

- Did David Alton’s Abortion Bill to cut the maximum age of the foetus to 18 weeks win or lose in the House of Commons?

- Who said and in what year ‘I am Jesus Christ and I announce the end of the world’?

- Which won the Oscar as Best Film in 1987—Platoon, Hannah and Her Sisters, The Mission or A Room With A View?

- In which year di...