![]()

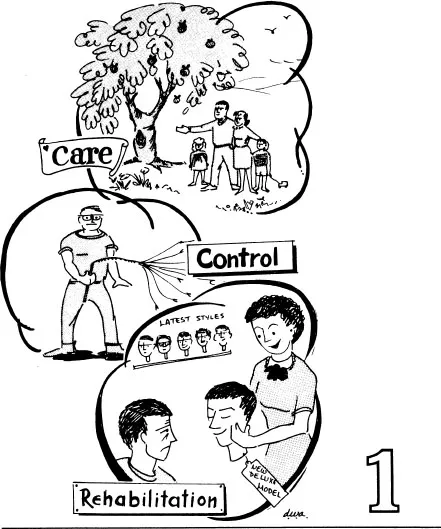

SOCIAL CARE, SOCIAL CONTROL, AND REHABILITATION

HUMAN SERVICE PROGRAM GOALS AND MEANS

OUTLINE

I. Issues

A. Policy—A Philosophy for Practice—Goals versus Means

B. Social Care, Social Control, and Rehabilitation

1. Individual and Situation Are Correlated

a. Changing the Individual will Result in Situational Change

b. Changing the Situation will Result in Individual Change

c. Interaction between Individual and Situational Change

2. Individual and Situation Are Not Correlated

3. Inverse Relationships between Care, Control, and Rehabilitation

a. Rehabilitation and Control

b. Rehabilitation and Care

c. Care and Control

C. Policy Implications of Conflicting or Congruent Goals

D. Prevention as a Goal of Human Service Programs

II. Definition

A. Social Care

B. Social Control

C. Rehabilitation

D. Program Goals—Means versus Ends

E. Program Goals—A Continuum

III. Implication of Analysis of Social Program Goals for Human Service Administration

A. Policy Formulation

B. Program Design

C. Program Monitoring and Control

IV. Summary

V. Application to Case “From Psychological Work to Social Work”

ISSUES

Policy—A Philosophy for Practice—Means versus Ends

Human service practitioners, whether administrators or direct service staff, need more than technical skills. They need a philosophy of service delivery—a framework that is related to the goals and purposes of human service programs and that will facilitate choice among different service delivery models. Administrators need a rationale that will assist them in allocating resources, establishing criteria for recruitment, developing staff reward systems, and evaluating the accomplishment of their programs. Technical knowledge of fiscal, personnel, and service modalities cannot provide the broad-based knowledge that is required in setting priorities and delivering services that are relevant and effectively meet consumer needs. This knowledge comes from the integration of the goals and purposes of human service programs with the understanding of administrative structures, processes, and skills (Demone and Harshbarger 1974:4). Direct service practitioners also require an understanding of the relationships of their efforts to the policies and purposes of the programs within which they work. This philosophy for practice provides a service rationale linked to the causes and solutions of social problems. This chapter explicates this philosophy for practice by identifying it with three major purposes of human services programs: social care, social control, and rehabilitation.

The need to integrate social welfare policy content with administrative and organizational knowledge and skill (Richan 1983, Saari 1977:47) becomes increasingly evident as the social welfare industry gives greater attention to the efficiency and effectiveness of organizations. Thus, Kahn (1976:39) has noted a tendency to underplay service content issues in favor of structural and organizational questions. He cites as an example how service integration efforts to correct inefficiency seldom specified case-level outcome criteria. Similarly, Street, Martin, and Gordon (1979) have characterized managers of human services as having an “ideology [which] focuses less on effects of agency operations than on a civil service conception of the organizational mission as extending and administering authorized programs in as fair and judicious a manner as is reasonable [p. 27].”

More efficient use of scarce resources is also being emphasized, especially as economic constraints force administrators to be concerned with costs in making decisions among alternative policies and programs. The pressure for better utilization of existing resources has thus raised the issue of the relative importance of, and the relationship between, efficiency and effectiveness of social programs. Should management focus its efforts on cutting costs, or should more attention be given to insuring that programs achieve their intended purposes? Are efficiency and effectiveness mutually exclusive or can they be complementary? Might not the emphasis on efficiency and productivity have a negative impact on the effectiveness of social welfare programs, that is, on the extent to which agencies can serve client needs? An approach is suggested here that may help avoid the substitution of efficiency for effectiveness by emphasizing social policy goals as an integral part of human service practice.

This issue of the degree of emphasis on efficiency versus effectiveness of social programs has also led to the question of who should manage human service programs, a manager or a professional. Is it preferable to have a nonprofessional, educated in business or public administration with technical administrative expertise, or is it more desirable to have a person trained in a human service discipline, who by this training should have a better understanding of the goals and purposes of social programs? It has been suggested (Etzioni 1964:83–84) that professionals should direct nonprofit organizations, in order to avoid goal displacement. The nonprofessional manager may emphasize efficiency or means of achieving program goals at the expense of the ends or primary purposes of the program. In contrast, a person trained in a particular professional field (e.g., medicine, nursing, or social work) should be able to direct the organization to achieve the primary goal of service to clients, with efficiency remaining the secondary goal. The introduction of specialized training in management in the various professions including hospital administration, nursing administration, educational administration, and social work administration (see Neugeboren 1971:34–47) is an attempt to integrate knowledge of a specialized profession with technical knowledge of administration.

Social administration has been defined as “the study of the social services whose object is the improvement of the conditions of life of the individual.” It is concerned with “the machinery of administration which organizes and dispenses various forms of social assistance” (Titmus 1958:14). However, much of the writing on social administration is directed at issues of social welfare policy, with less attention given to the organizational problems involved in service delivery. A more directed effort at integration of policy and administration is Donnison and Chapman’s Social Policy and Administration (1965). Specifically, this very important book attempts to integrate knowledge of organizational task, structure, and process with policy analysis of service delivery in substantive areas such as housing, child welfare, family welfare, and education.

Returning to the discussion of which profession is best equipped to manage human service organizations, it is of interest to note that in Great Britain the study of social administration was first introduced as training for social workers (Donnison and Chapman 1965:26). However, regardless of who the manager is, it will be necessary also to integrate substantive knowledge of social policy with knowledge of practice to avoid the overemphasis on means to the detriment of the goal of client benefit (Neugeboren 1979). That is, social policy analysis based on understanding of goals of social programs in relationship to social problems such as poverty, corrections, mental illness, and ill health needs to be integrated with knowledge of organizational opportunities and constraints on human service practice. This integration will be explicated in the chapters that follow through the analysis of goals and purposes of human service programs within three major areas: social care, social control, and rehabilitation.

Social Care, Social Control, and Rehabilitation

The goals of social programs—social care, social control, and rehabilitation—need to be differentiated from the overall mission—client benefit. That is, client benefit is the end to be achieved through the alternative or combined means of social care, social control, and rehabilitation. Clarity as to the means-ends relationship is needed to insure that client benefit remains the primary purpose of human service programs. The overall mission of human service programs is the improvement of the quality of life of persons who are in distress and suffer from such problems as mental illness, poverty, mental retardation, ill health, problems of old age, crime, child abuse and neglect, inadequate housing, etc. In short, the ultimate mission is to benefit people who are in difficulty and require assistance.

In a discussion of medical care organizations Mechanic, noting that bureaucratically designed institutions treat clients in an impersonal and de-humanizing way, concludes that: “our society desperately needs experiments in new forms of social organization that provide renewed bases for personal commitment, that contribute to the deprofessionalization of the expert, and that encourage a higher level of caring. … Medicine without caring is technics run wild [1976:3; emphasis added].” We can equate policy with clarity regarding the effect of programs on client benefit. Therefore, an understanding of how the goals of human service programs are influenced by administrative means can facilitate the “caring” that Mechanic advocates and thereby facilitate the mission of client benefit.

In this analysis of purposes of human service programs we will be referring to the operative goals. The operative goals are the actual goals, which may or may not differ from the official goals (see Chapter 2). These operative goals are determined by the activities and results achieved by the human service program.

The distinction among these three goals of human service programs (care, control, and rehabilitation) rests on the focus of intervention of these programs. Social care, social control, and rehabilitation have as their targets of intervention either the individual or the situation surrounding the individual.

Social care is concerned primarily with changing the situation or environment for clients. Rehabilitation, in contrast, is directed at changing the individual. Social control is concerned with containment of the individual’s deviant behavior. This threefold classification is being used here in order to make explicit the primary purposes of human service programs. Although most programs will have multiple goals, administrators and practitioners should be aware of the major emphasis of their programs. An awareness of where the resources and efforts of staff are directed should facilitate more effective and efficient service delivery.

The above typology of program goals may be viewed by some as based on a false dichotomy (see W. Schwartz 1969:22–43). There are those who believe that separating interventions into categories of individual versus situational change denies the need for change in both areas at the same time. Thus, the stress in social work on “psychosocial” intervention assumes the need to direct efforts at changing situations and individuals.

The distinction between changing persons versus policies has led to the proposal of dividing social work practice into two areas: one providing direct service to people with problems in social functioning, and the other dealing with programs and policies. Those who propose this division hold that the knowledge and skills required in the two areas are critically different: “The interactional skills of the indirect services tend to focus more on the sociopolitical variables in relationships than on social-psychological variables (Gilbert, Miller, and Specht 1980:37).” They feel that the generalist approach to practice “ascends to conceptual levels that obscure real and important differences [Gilbert, Miller, and Specht 1980:36].”

We, too, will make the assumption that there is a distinction between changing people and changing policies and programs, associated with the distinction between direct and indirect practice. However, we also assume that direct practice can include not only people change (rehabilitation), but also modification of their situations (social care), which requires sociopolitical skills.

It is possible that if one were to examine the daily activities of persons employed by human service programs one would determine that individual or situation change is given more emphasis and priority. This priority is probably influenced by the ideologies and technologies available to the persons working in the organizations. Mechanic (1974) suggests that in the health field the distribution of care reflects ideological preferences and medical knowledge, as well as the system of power. (See Chapters 13 and 14 for discussion of ideologies and technologies.) Regardless of how one feels about dichotomizing and typologizing program goals, what human service organizations give priority to in actuality is basically an empirical question. And regardless of the answers to this empirical question, one can raise the issue of what the goals of human service programs should be. Given the kinds of problems presented by the consumers of human service programs, which is the more appropriate goal: care, control, or rehabilitation? Under what circumstance is change of the individual more valid than modification of the situation? Should a juvenile delinquent be treated (rehabilitation), given a job (care), or punished (control) or a combination of all three? Are care, control, and treatment congruent or conflicting goals? The criticisms of combining treatment and punishment, “coerced cure” (N. Morris, 1974), suggest that rehabilitation and punishment are not compatible. In light of the limitation in resources which should be given priority? This decision may be made by the direct service worker based on his or her particular philosophy and skills. From a policy point of view it would seem important that administrators be clear as to which goal is most appropriate for meeting the needs of particular client groups.

The above can be illustrated by the debate in the health field over the degree to which specialization is required. Underlying the issue of division of labor between general practitioners and specialists is the question of the functions to be performed by these two types of practitioners—care versus treatment. Overelaboration of medical specialties is believed to result in a fragmented pattern of service (Mechanic 1974:49). The effort to establish the role of the general practitioner by the development of the specialization of family medicine has been questioned on the grounds that certain problems prevalent in general practice, such as alcoholism and drug abuse, require knowledge not presently available in the education for family practice (Mechanic 1974:50). A more critical question would be whether the nature of the problems brought to medical practitioners are in fact “medical” problems requiring “treatment.” If problems such as alcoholism and drug abuse are defined as “social” problems, then the provision of rehabilitation and treatment may be less appropriate than a social care type of intervention directed at environmental modification.

Epidemiological investigations of the occurrence of illness and seeking of medical care suggest that much of the motivation for contact with the health care system results from environmental stress. … The technological structure, which characterizes modern medicine, … is a good deal less than perfectly responsive to the forces bringing patients into the health care system [Mechanic 1976:11].

Another factor that should influence these policy choices regarding the goals of human services is that of the relative effectiveness of these three types of intervention. Given the...