This is a test

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Short History of Roman Law

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The most important creation of the Romans was their law. In this book, Dr Tellegen-Couperus discusses the way in which the Roman jurists created and developed law and the way in which Roman law has come down to us. Special attention is given to questions such as `who were the jurists and their law schools' and to the close connection between jurists and the politics of their time.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access A Short History of Roman Law by Olga Tellegen-Couperus in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Part I

FROM MONARCHY TO EARLY REPUBLIC (-367 BC)

1

FROM MONARCHY TO EARLY REPUBLIC: GENERAL OUTLINE

1.1. THE SOURCES

Very little factual information is available about the earliest period of Roman history. The oldest historical studies that have survived date from the beginning of the first century AD. The authors of these studies, e.g. Livy, Plutarch and Dionysius of Halicarnassus, made use of the works of older historians who lived in the third to the first centuries BC and described the history of Rome year by year (the so-called annalists). However, the sections of their works relating to the early period of Rome’s history were far from reliable. Although the annalists had access to a wealth of source material for the period dating from 387 BC up to their own day, there were practically no written documents left for the period before that year. These documents were lost in 387 BC when Rome was conquered and set on fire by the Celts. In order to fill the gaps in the source material the annalists made use of legends; although these legends may have been based partly on history they were certainly not historically reliable. The annalists elaborated these legends using their imagination and sometimes altered the chronological order of the events. Information about the founding of Rome and its early history therefore has always to be checked against information obtained with the help of other disciplines such as archaeology and linguistics.

Our knowledge of the oldest form of Roman law is also based on sources of later date. These sources include some of the literary sources mentioned above as well as some juridical sources such as the Enchiridion of Pomponius and the Institutes of Gaius, both dating from the second century AD; legal historians have doubts about the reliability of these sources as well, but nowadays there is a tendency for some Romanists to regard them as useful nevertheless.

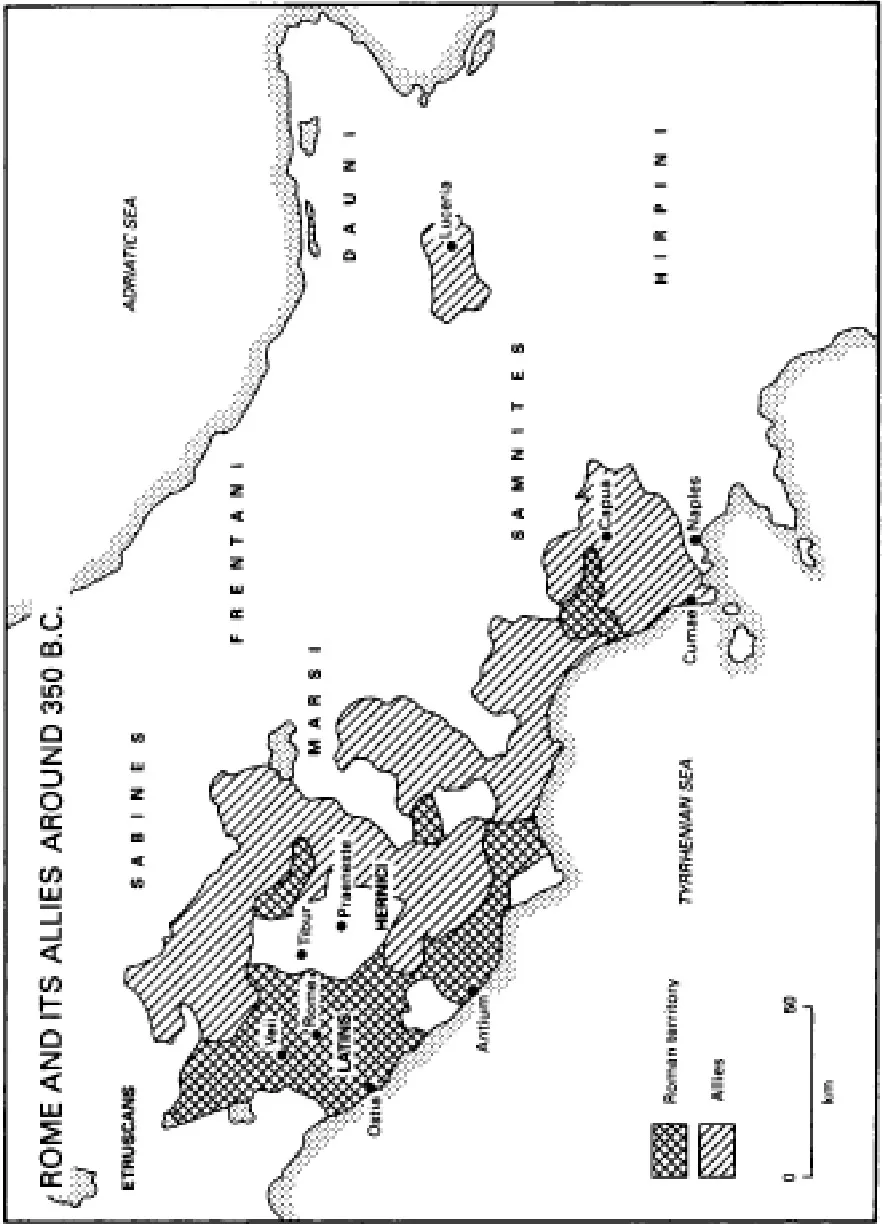

1.2. THE TERRITORY

As from 1000 BC various tribes came from the Danube basin and began to settle on the Italian peninsula. Some of them were to have a special influence on the founding and development of Rome. They were Indo-European tribes who were known collectively as Italians; two of these Italian tribes, the Latins and the Sabines, settled in Latium on the left bank of the Tiber1. They lived in a number of small settlements and engaged in agriculture and cattle-rearing. Some of these settlements were on the hills in the area where Rome was built later on. In the course of the seventh century BC the inhabitants of these hill-settlements formed an alliance and they gradually obtained a powerful position in Latium. It was easy to cross the Tiber at this spot, so the alliance was able to control the trade between the left bank of the Tiber and the Etruscans on the right bank. It was the Etruscans who ultimately founded Rome.

Until recently it was assumed that the Etruscans came to Italy from Asia Minor about 900–800 BC and settled initially on the coast of modern Tuscany. The latest view, however, is that they settled in Italy much earlier than this and that they formed a complex of eastern, continental and indigenous elements2. The Etruscans differed from the Italians in many respects. Unlike Latin, Greek and Celtic, their language, Etruscan, did not belong to the Indo-European group. As a result the Etruscans were long regarded as a mysterious people, but now much more is known about them. Because the Etruscans adopted the Greek alphabet and made only slight changes, Etruscan inscriptions are easy to read. We have known the exact meaning of most of their words for several decades now. Our information about the Etruscans is therefore no longer based solely on the work of Greek and Roman historians and archaeological finds (e.g. the wall-paintings on the graves in Tarquinia and Chiusi). Recently we have also been able to consult about 10,000 inscriptions that have survived. As a result, we know that the Etruscans, unlike the Latins and the Sabines, did not live in small scattered settlements. They lived in independent city-states which formed the centre of local trade and politics. Until the fifth century BC the city-state was ruled by a kingand thereafter by a magistrate. Private law of the Etruscans, and particularly the law of persons, was very different from, for example, Roman private law.3 Their culture was more highly developed than that of the Latins and the Sabines. We know from archaeological finds that the Etruscans had considerable knowledge of architecture and mining and were able to install a drainage system. Like the Italian tribes the Etruscans made their living from agriculture and cattle-rearing, but they also engaged in trade; because of their superior technical knowledge they were able to develop some sort of industry which produced ceramics, materials, implements and utensils, jewellery and ornaments. The Etruscans were also fearsome pirates who plundered ships in the coastal waters of the Mediterranean. In the course of the seventh century BC the Etruscans extended their power in a south-easterly direction, to Latium and Campania, and introduced their way of life to those areas.

According to legend Rome was founded by Romulus in 753 BC; on the basis of archaeological evidence, however, it seems much more likely that Rome was founded by the Etruscans in the seventh century BC. The territory of the Latins and Sabines was of great strategic importance for the Etruscans. This was why they founded the city-state of Rome on that site. They did this in accordance with their own customs: they built temples and reservoirs, cisterns and a city wall; they drained the swamps between the hills, they organised the people into political and military units and let the city-state be governed by a king who was generally of Etruscan origin. Tradition has it that the last Etruscan king was overthrown and driven out of Rome in 509 BC. This event marked the beginning of a new era for Rome. The expansion of the Etruscans towards the south ceased and they even had to withdraw from Campania and Latium. Rome became a republic governed by a senate and magistrates.

The young republic, however, was surrounded by a number of powerful neighbours: the south of Italy was in the hands of some Greek colonies and the Etruscans still constituted a formidable force in the north. In Latium there were some other city-states besides Rome which had joined to form the Latin alliance. In 493 BC Rome came into this alliance too, as an equal partner rather than as a member. As from the end of the fifth century BC the Romans began to extend their territory. First of all they moved northwards. As a result of a war against the Etruscans (406–396 BC) Rome acquired pan of Tuscany; from then onwards the Tiber no longer formed Rome’s northern frontier. About this time Celtic tribes settled in the Po valley. They soon decided to extend their territory southwards; they managed to defeat the Romans, capture Rome and set it on fire (387 BC); the citadel, the Capitol, was probably the only building left standing. Finally the Celts were repulsed and they retreated north wards. Throughout the fourth century and at the beginning of the third century BC the Romans fought battles: against the Samnites (a tribe from the Apennine area), against the Latin alliance which rose in revolt, against the Etruscans and the Celts and finally against the Greek colonies in the south of Italy.

By the time these battles were over, the Romans had subjugated the tribes in central and southern Italy. This did not mean that these tribes were governed from Rome: the various tribes were more or less allowed to rule their own areas but they were made subordinate to Rome in very different ways.

1.3. THE POPULATION

1.3.1. Familia and gens

Roman society was made up of two elements, the familia and the gens. A familia consisted of all those persons who were in some way subject to the power of a pater familias. 4 This power could be based on parentage, marriage or adoption and was in principle unlimited. Religious norms imposed a certain number of constraints and the possible abuse of power by a pater familias was kept in check by strong social control. Within the familia the pater familias was the only person who had any rights in private law.

Being subject to the power of a pater familias had nothing to do with age; a person was in this position until the pater familias died or relinquished his power in a formal manner, e.g. by means of emancipation the person concerned was then independent and could have his own property (sui iuris).

Familiae with a common progenitor (even if he was a legendary figure) together founded a gens and had a common gens-name.5 They could hold meetings and pass resolutions that were binding on the members, and they had a common cult. According to Livy (Ab urbe condita, 10.8.9) at first only patricians formed a gens, but names of old plebeian gentes are also mentioned in the sources. The law of the XII Tables of 449 BC contained rules on guardianship and intestate succession for the gentes; these rules were applied until the end of the republic. The gentes themselves continued to exist during the early empire, but then they no longer had any juridical function.

1.3.2. Patricians and plebeians

This early period of Roman history is characterized by the division of the population into patricians and plebeians. Nobody is quite sure how this division originated; it may have been based on ethnic differences (for instance, the plebeians were of Latin origin and the patricians were the descendants of the Sabines, or vice versa), but we have no proof and such theories can only be speculative.6 The sources, however, do demonstrate that the plebeians were not regarded as foreigners but were Roman citizens, just like the patricians. The differences between the patricians and the plebeians were clearly visible from their respective economic and social position. The patricians formed a kind of nobility; they owned a considerable amount of land and kept cattle and slaves. They were entitled to serve as magistrates and priests and because of the voting system had a decisive influence on legislation (see section 2.2.3). The plebeians on the other hand were mainly artisans and small farmers; in times of war they had no slaves to keep their businesses running and this increased their chance of impoverishment. Furthermore, as mentioned already, they were not allowed to hold public office and, as a result of the above-mentioned voting system, they had very little influence on legislation. Finally, in the law of the XII Tables it was stated that intermarriage between patricians and plebeians was forbidden.7

In the early years of the republic the number of impoverished plebeians increased whereas some plebeian families became wealthy and sought to have the same rights as the patricians. This gave rise to considerable tensions. In the long struggle between the orders which began about 500 BC and continued until 286 BC the differences in the rights of patricians and plebeians were gradually removed. According to tradition, in 471 BC the plebeians were granted the right to hold their own assemblies (called concilia plebis) and choose their own officers, called tribunes; the decisions made by these assemblies (plebiscites) applied exclusively to the plebeians. The patricians did not consider themselves bound by these decisions. The next important step was the recording of the law in writing in the XII Tables; this enabled the plebeians to become acquainted with the law and to protect themselves more effectively against patricians who, by serving as priests or magistrates, abused their power. The XII Tables will be discussed in more detail in section 3.2. Shortly after this law had come into being, a lex Canuleia removed the ban on intermarriage between patricians and plebeians. The leges Liciniae Sextiae of 367 BC opened the way for plebeians to serve in the top ranks of the magistrature and become, for instance, consuls. And finally the lex Hortensia of 286 BC decreed that the plebiscites were binding for all the Roman people, including patricians. The political distinction between patricians and plebeians had thus disappeared for ever; the only difference that remained was between rich and poor citizens.

1.3.3. Citizenship and clientela

Rome, like other city-states in antiquity, observed the personality principle: each person lived according to the law of the town to which he or she belonged. Although the Romans conquered the tribes of central and southern Italy, this did not mean that these tribes were automatically granted Roman citizenship: the various tribes retained their own form of law but were also allowed to use Roman law to a certain extent. In Rome, this situation stimulated, quite early on, a large-scale development of the phenomenon known as clientela.

It is not certain how the clientela came into being. The clientes may originally have been foreigners who had settled in Rome and had placed themselves under the protection of a Roman gens. Anyway, in the early republic it was mainly Roman citizens with a weak social and economic position (namely plebeians) who sought the protection of a Roman citizen in high office; this Roman then became their patron. In a juridical sense the clientes were free but they were expected to show their patron respect and loyalty and support him in his political ambitions; this meant for instance that in the comitia they had to vote in the same way as their patron.8 In return a patron had to give his clientes the use of a piece of land or assist them in a lawsuit by giving legal advice or appearing for them in court. He was not supposed to take legal action against his clientes or to give evidence against them in a trial. The clientela phenomenon continued throughout Roman history, but from the empire onwards it played a less important role.

1.4. ECONOMY

For a long time after its foundation the city-state of Rome occupied quite a small area. About 500 BC, Rome covered an area of only 700–800 km2. Agriculture and cattle-rearing were the main means of livelihood. It is not clear whether the Romans at that time were familiar with the principle of private ownership; perhaps at first only ownership of movables such as cattle and implements was possible; ownership of immovables may not have been possible until later.9

Because of Rome’s favourable situation on the Tiber—and its proximity to the via Salaria—the city soon developed as a trading-centre. Until the late fourth century BC the Romans had no coinage, but instead they used pieces of bronze: prices of goods were determined by the weight of an amount of bronze. The weight was determined by a weigher (libripens) who weighed the bronze (aes) on scales (libra). After the introduction of coins, the procedure continued for centuries as a formality for certain legal acts such as the emancipa...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- MAPS

- PREFACE

- ABBREVIATIONS

- INTRODUCTION

- Part I FROM MONARCHY TO EARLY REPUBLIC (-367 BC)

- PART II THE LATE REPUBLIC (367–27 BC)

- PART III THE PRINCIPATE (27 BC-284)

- PART IV THE DOMINATE (284–565)

- EPILOGUE

- CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY