1

MARRIAGE

INTRODUCTION

I think it would please you to have me there with the whole household, and yet you leave the choice to me. This you do for your courtesy, and I am not worthy of so much honour. I have resolved to go not only to Pisa, but to the world’s end, if it pleases you.

(Origo 1959:162)

You bid me make merry and be of good cheer. I have naught in the world to make me merry; you could do so if you would, but you will not…. Each night, when I lie abed, I remember that you must wake until dawn. And then you bid me be of good cheer.

(Origo 1959:164)

Margherita Datini’s letter to her husband, a merchant from the small Italian town of Prato, cited first above, was dictated by her in 1382; the second, rather tarter missive to the same recipient dates from a few years later. Francesco Datini was about 42 when he married his 16-year-old wife from the lesser Florentine nobility in Avignon in 1377, a marriage which was to last thirty-three years. Margherita was taught to read and write by a family friend only at the age of 30, but her letters, together with the fifteenth-century English Paston letters, are among the few writings by ordinary married women in our period. Although the great majority of the female population were married at some point in their lives, the writings by women which survive are overwhelmingly those of monastic women, who had never been, or were no longer, married. Yet the universality of marriage in one form or another is such that there are many texts which serve to flesh out a conception of the changing institution emerging in law codes and theological writing throughout the period. Marriage customs varied by region: in some places women were married when very young to men some ten to fifteen years older than they were (a pattern associated with southern Europe), or they married men of like age at roughly the same age as women now marry in the West (a northern European pattern). These patterns were heavily modified by class: the lower the class, the more choice the partners might have. (Goldberg 1992 and Smith 1992 give full summaries of the debates surrounding European marriage patterns.)

Marriage as institution

At the most general level marriage is a social mechanism designed to regulate the distribution of women between male members of society and to formalize the links between a man and his offspring. In western Europe men have tended to have only one wife at a time: serial monogamy, or marriage to a (legal) wife with a number of concubines ensured variety in the man’s sexual life. In the early period, the concubine might co-exist with the wife, or—a pattern frequent in early France—the young nobleman might take an official concubine in his youth, replacing her with a wife of rank equal to his, who would bear him legitimate children. Separation from the concubine, who might also have borne children and have been a partner for many years, was not always easy, as demonstrated by the case of Lothar and Waldrada outlined below. Saint Augustine records his misery when, as his marriage to a young heiress approached, he was forced to give up the woman with whom he had been living for many years:

The woman with whom I had been living was torn from my side as an obstacle to my marriage and this was a blow which crushed my heart to bleeding, because I loved her dearly. She went back to Africa, vowing never to give herself to any other man, and left with me the son whom she had borne me>the wound I had received when my first mistress was wrenched away showed no signs of healing. At first the pain was sharp and searing, but then the wound began to fester, and though the pain was duller there was all the less hope of a cure.

(Augustine 1961:133)

Augustine does not record the fate of his discarded mistress; similar women who have lived in non-marital arrangements tend to disappear from the record when the relationship is terminated. Charlemagne did not allow his daughters to marry, lest the alliances thus formed with other families should weaken his own and his sons’ positions. However, he tolerated his daughters taking sexual partners outside marriage. Their brother, Louis the Pious, was less broad-minded: on his accession to the throne the sisters were packed off to the convent of Chelles where their aunt Gisela was abbess. The most famous of all the marital wrangles of the early French kings was occasioned by the passion of Lothar of Lotharingia (roughly eastern France, west Germany and north Italy) for the concubine Waldrada, with whom he had lived before his marriage to Theutberga. Lothar married Theutberga for political reasons; although Waldrada came from the lower nobility she unfortunately ‘did not have a brother who could guarantee the defence of the Alpine passes for Lotharingia’ (Wemple 1981:90). From 858 to 869 the clergy of Lotharingia, and chiefly the redoubtable Bishop Hincmar of Reims, were occupied with the question of Lothar’s divorce from Theutberga. The political advantages of alliance with Theutberga’s family had now passed, and Lothar wanted to marry his former concubine. Lothar’s great-grandfather, Charlemagne, had easily repudiated one of his wives and lived with several concubines in his old age, but Lothar was driven to accusing his wife of incest, of conceiving through femoral intercourse and of procuring an abortion without damaging her virginity, and was still unable to get rid of her. The case was still in progress when he died (Bishop 1985:53–84; Wemple 1992:180).

In early medieval Europe divorce seems to have been relatively easy to obtain. The Icelandic sagas suggest that a husband or wife simply had to declare before witnesses that they were divorcing their spouse, as Thrain does (p. 27 below). Anglo-Saxon laws allowed a wife to keep half of the couple’s joint property if she had custody of the children (Fell 1984:64). But by the tenth century marriage had changed from an essentially private arrangement between a man and a woman and their respective families into a Christian and lifelong monogamous partnership. It was a difficult ideal to impress upon the male members of the ruling classes: the wife had to have useful kindred to cement political alliances, be able to provide sons and heirs in sufficient numbers to ensure inheritance, and, increasingly, to be a companion to her husband. The ninth-century writer Christian of Corbie warns:

[Be she] gluttonous, quarrelsome or sickly, a wife must be kept until the day of her death, except if by mutual agreement both partners withdraw from the world. Therefore, before he accepts a wife, a man must get to know her well, both with regard to her character and health. He should not do anything rash that may cause him sorrow for a long time. If all decisions are to be made with advice, this one even more so; in matrimony a man surrenders himself. Most men, when they choose a wife, look for seven [sic] qualities: nobility, wealth, looks, health, intelligence, and character. Two of these, intelligence and character, are more important than the rest. If these two are missing, the others might be lost.

(cited from Wemple 1981:88)

Marriage, then, had come to be for life, save in exceptional circumstances. Incest was one of these. By the 1060s, in the course of the Gregorian reforms, the theologian Peter Damian extended the consanguinity prohibitions to marriages within the sixth degree of kinship. However, few people, even among the nobility, were able to reckon up their fifth cousins accurately, and over time the European aristocracy had become very closely connected. This had its advantages: a marriage could be contracted apparently in all innocence only for the true kinship relation to emerge some time later if one or other of the partners no longer wished to be married. A case in point is that of Louis VII and Eleanor of Aquitaine. The two parties in the marriage were related in the fourth and fifth degrees, but it was not until they had been married for twelve years, during which time Eleanor had produced only two children, both daughters, that the consanguinity issue was raised. Eleanor and Louis were divorced, and Louis married two subsequent wives, the third of whom was his son-in-law’s sister. As a hindrance to marriage consanguinity could be overlooked if the need arose. By the thirteenth century, overwhelmed by the number of annulment cases which the extended consanguinity laws had brought about, the Church had to retreat and the restrictions were eased (Brooke 1991:134–6).

Adultery by the female partner (male adultery was rarely considered significant) provided another ground for divorce; however, the Church did not allow the parties to remarry in this instance. Laws concerning adultery varied: some codes permitted the aggrieved man to kill both wife and lover if he caught them in flagrante. One Anglo-Danish law made under Knut condemns the adulterous wife to having her nose cut off, while an earlier law simply requires the lover to provide a new wife for the outraged husband, presumably making himself responsible for the payments to the new wife’s kin (Fell 1984:64).

Making a marriage

Even though the Church became increasingly concerned in promoting the ideal of lifelong monogamy and constructing theories of marriage, it had little part to play in the actual ceremony. Broadly speaking, a marriage had three stages: petitio (negotiations), desponsatio (betrothal) and nuptae (wedding). The sequence is clearly illustrated in excerpt 4 below. The families concerned would make contact, either directly or through intermediaries, and negotiate the financial arrangements. At a private, though legally binding, ceremony involving an oral or written contract, the parties would pledge themselves, and at some subsequent time, the public celebration, often, though not necessarily, including a nuptial mass, would take place and the marriage be consummated.

When did the couple actually become married during this process? According to the Roman jurist Ulpian, ‘consent makes the marriage’, and thus the betrothal came to be regarded as binding. Ulpian had in mind the consent of the families, arrived at after the negotiations, not the consent of the parties themselves, though over time the consent of the husband and wife was seen to be what mattered. After betrothal the parties could not extricate themselves from the match without incurring penalties. Consummation might also occur after betrothal without moral disapproval; in the Spanish frontier towns of Castile and Léon in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, records show an assumption that the betrothed couple would sleep together, though problems would arise in the case of subsequent repudiation (Dillard 1984:57).

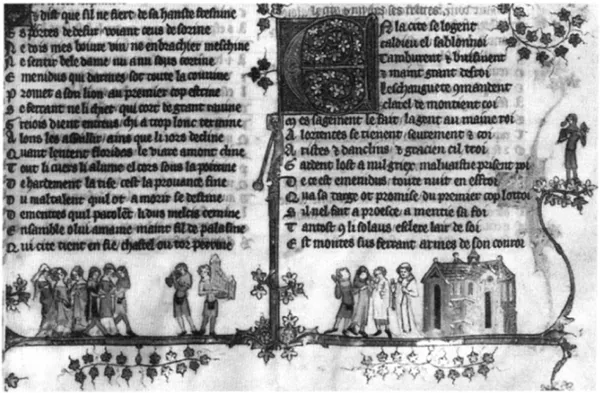

Betrothal involved consent in one of two ways. In the 1150s Peter Lombard had elaborated the distinction between consent made per verba de futuro, words in the future tense, which constituted a promise to marry at some future date, and a promise per verba de praesenti, words in the present tense (i.e. I, N, marry you, M), which constituted an indissoluble union. Consent per verba de futuro only constituted a marriage after consummation. Marriages per verba de praesenti in fact remained legal in England until the Hardwick Marriage Act of 1753. In 1215 the Fourth Lateran Council moved to require ecclesiastical participation in weddings, but clandestine marriages were not invalidated by this, despite the difficulties attendant upon proving that such marriages had taken place if one or other party should change their mind. The Sarum Ritual dating from 1085 makes clear that, in England at least, the expectation was of a public betrothal ‘at the church door,’ where the whole community could establish that there was no impediment to the marriage and witness the exchange of vows and ring (Conway 1993; Amt 1993:83–9). The ceremony did not move inside the church until after the Reformation (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 A bride, accompanied by her male kin, maidens, musicians, and a married woman at the rear approach the church door, where the priest, the bridegroom, his kin (one of whom is listening out for the musicians) wait. From a fourteenth-century Flemish manuscript, MS Bodl 264 fol. 105v, Bodleian Library, Oxford.

What was marriage for? According to Augustine’s influential analysis, the goods of marriage were: fides, proles, sacramentum (mutual sexual fidelity, children and the function of marriage as a sign of the union between Christ and the Church). Thus marriage was to be exclusive, all sexual acts were to be open to the possibility of conception, and the union was indissoluble (Payer 1993:70–1). In the thirteenth century, in the writings of Thomas Aquinas and thereafter, marriage was analysed in terms of intentions (causae): what was marriage intended for? First, marriage was intended for procreation, second to pay the marriage debt (see below, p. 16), third to avoid fornication, and finally for pleasure. The first two reasons were morally straightforward, while the second two caused innumerable problems for the Church in the later medieval period as theologians tried to determine how sinful sexual acts undertaken primarily, or partly, for pleasure might be (Payer 1993: 111–31).

Thus, in philosophical and theological terms, marriage seemed to require consummation; an unconsummated marriage fulfilled none of the causae above, and negated one of Augustine’s goods. The Church therefore became troubled by its failure to include consummation in its formal definition of marriage. Early in the period unconsummated marriages had been regarded as meritorious, an assessment stemming in part from Augustine’s pronouncement that the marriage of the Virgin Mary and Joseph, though unconsummated, was nevertheless a true marriage (Clark 1991:23). Thus Bede celebrates Queen Ætheldred of Northumbria, who kept her virginity through two marriages, much to the annoyance of her second husband Ecgfrith. Henry III of Germany (1017–56) and his wife Cunégonde were believed by later chroniclers to have had a manage blanc—at all events no children were born and Henry was canonized some hundred years after his death (Duby 1983–4: 57–8). By the late twelfth century Pope Alexander III (1159–81), deeply conscious of the significance of the biblical phrase ‘una caro’ (one flesh) in describing the nature of marriage, came to see consummation as an essential part of the sacrament (as it had now been defined) (Brooke 1991:132–3). Failure to consummate thus became a ground for annulment; a ground which stored up as much trouble for the papal courts as the consanguinity rules. Consummation and consent now made the marriage (Amt 1993:79–83).

Marriage and property

The disposition of property at a wedding changed greatly over the medieval period. At the beginning of the period, in the parts of Europe under non-Roman law, the bride-price was paid by the groom to the bride’s family (later the bride herself), and the wife would receive a ‘morning-gift’ on the morning after the marriage was consummated. Some Germanic law codes limited the amount of the morning-gift, others were more generous: Chilperic of the Franks gave his Visigothic queen, Galswinth, the cities of Bordeaux, Limoges, Cahors, Lescar and Cieutat. These were inherited from Galswinth, whom Chilperic subsequently had garrotted, by her sister Brunhild (Gregory of Tours 1974:505). Gradually, the bride-price came to be paid to the wife herself, often in the form of a dower which would form the woman’s financial security when she became a widow.

In the 1140s the Roman dowry system was instituted, probably because there were now more young women of marriageable age than young men, and because marriage patterns were changing in southern Europe. Men now tended to marry girls who were ten years or more younger than they were, and thus the pool of marriageable women was enlarged (Hughes 1978). The new system was found first in Italian towns, from where it spread rapidly across Europe. Now property passed on marriage from wife’s family to husband’s; Dante himself, in the Paradiso, refers to the fear which a father felt at the birth of a daughter as he anticipated her future dowry expenses (Dante 1971:219). By the end of the period dowry inflation in Italy had reached such a peak that the Florentines established the Monte del Doti, a bank into which an anxious father could pay a deposit at the birth of his infant daughter. This would mature into her dowry payment when she became marriageable, or would provide a settlement for entry to a convent (Brooke 1991:15–16).

Early historians of Anglo-Saxon and Germanic societies argued that the bride-price system meant that Germanic women must have lacked status since they were ‘bought’ at marriage (Fell 1984:16); other historians ascribe women’s gradual loss of power through the medieval period to the institution of the dowry system (Stuard 1987:161). Neither contention gives the whole picture, however, for women’s status depended far more on their capacity to own, and to buy and sell property in their own right, and to inherit property from parents and husbands. These rights varied enormously in both time and place. The Merovingian queen had control over the royal treasury at the death of her husband, thus, as Pauline Stafford writes, ‘the masterplan of a sixth- or seventh-century usurper had three stages: murder the king, get the gold-hoard, marry the widow. Since the widow usually sat on the gold the two went together’ (Stafford 1983:50). Anglo-Saxon women might buy and sell property independently of their husbands, and bequeath it away from their children back to their own kin, if they wished (Amt 1993:130–6). Royal women were able to use their lands for monastic foundations, a development which was popular with the Church, if not always with the royal family (see p. 157 below). Under the dowry system, daughters usually received their portion of the family inheritance at marriage, instead of at the parents’ death, when they might expect to inherit nothing further. The dowry was meant to be held in trust for the wife’s support after her husband’s death, but very often the wife was in no position to prevent her husband from selling or mortgaging her property.

In Castile the townswomen benefited from egalitarian legislation (the law of acquisitions) which held that all property jointly acquired, such as the profits from a husband-and-wife business partnership, were owned in common, and there were efficient checks on a husband’s right to dispose of family property (Dillard 1984: 68). The law of acquisitions thus ‘acknowledged [wives’] importance in the accumulati...