![]()

Part I

![]()

1

Introduction

THE HISTORICAL STUDY OF LANGUAGE

This book is not a conventional history of English. Rather, it tries to show how the discipline of linguistic history may be pursued—a rather different matter. It does this by using selected phenomena in the history of English to exemplify the dynamic processes of change involved. In so doing it tries to address the question of linguistic change: why does change happen, and why does it happen at the time and in the way that it does?

In answering these questions, this book, rather obviously, holds it as axiomatic that human language is both a cultural and a systematic phenomenon, and that both these characteristics need to be borne in mind when addressing the question of linguistic change. On the one hand, it is held here that the various changes at an intralinguistic level which are held to be the prime concern of writers of linguistic history—changes in writing systems, pronunciation, grammar or lexicon—cannot be meaningfully accounted for without reference to the extralinguistic contexts (historical, geographical, sociological) in which these phenomena are situated. Language is plainly a social phenomenon—if societies did not exist, there would be no language—and it follows from this that an asocial approach to its study has a comparatively limited (because formal) interest.

This conclusion applies most uncontroversially to diachronic linguistics (i.e. time-situated linguistics). If we attempt to explain language change entirely intralinguistically, without ultimate reference to extralinguistic factors, then, it is argued here, the explanation will ultimately fail.

But it is also held here that linguistic change can operate intralinguistically, that is, without immediate reference to external, non-linguistic factors. The key argument in support of this axiom is that linguistic changes, once they have themselves been implemented, interact with each other to produce further change.

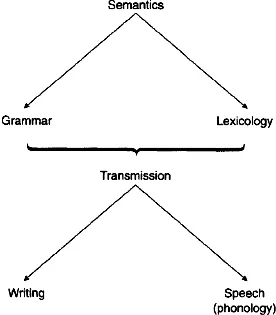

To clarify these points, it may be useful to model the structure of natural language diagrammatically. Figure 1.1 is an attempt to schematise the way in which language is used to communicate ideas. The deepest level of language, in this diagram, is semantics, that is, the level of meaning. (There are philosophical questions as to whether semantics can be deemed properly a part of the linguistic system, but, given that language is about the transmission of meaning (very broadly defined) it seems perverse to ignore it here.) Meaning is expressed linguistically through the grammar and lexis of a language; in turn, the grammar and lexis of a language are transmitted to other language-users through speech or (a comparatively recent development in human history) through writing.

The model of language given in Figure 1.1 has its uses, but it is important to be aware of its limitations. It is essentially a static model, a snapshot; it depicts what happens when a single linguistic ‘event’ (a word, a

Figure 1.1 The levels of language (hierarchical model)

grammatical construction, a sound or a spelling) takes place. It is hierarchical in orientation, placing semantics at the top of a tree in which transmission occupies a lowly position. Above all for the purposes of this book, it is limited because it does not indicate any point where change might take place.

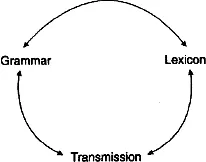

There are methodological advantages to treating each level of language (written and spoken transmission, grammar, semantics and lexicon) separately, for it is obvious that to attempt to cover every level at once brings with it a threat of incoherence. Nevertheless the approach has dangers. What evidence we have indicates that the human brain uses each level of language in an integrated way, handling them all simultaneously and interactively, and in diachronic study it will frequently, if not generally, be found that change in one level of language relates intimately to change in others. If language is systematic—and it must be, for otherwise it would be impossible to use it to express meaning, however broadly we define that concept—then movement in one part of the system must have an effect or effects on other parts.

Languages, in short, are systems in which everything is connected to everything else (tout se tient, in the words of de Saussure, Grammont and their followers; see Grammont 1933, passim). This structural notion is the major insight of linguistics since the modern discipline was founded in the nineteenth century, and it is at the heart of the subject's claim for non-trivial status. In sum, we must expect that any given linguistic event is the result of complex interaction between levels of language, and between language itself and the sociohistorical setting in which it is situated. It is therefore necessary, in our modelling of language, to supplement the simple communicative model of Figure 1.1 with a non-hierarchical one, offered here as Figure 1.2 (after Samuels 1972: 141). This latter model allows for the process of change; disruption and subsequent reaction can happen at any point in the system, and thus any model of language reflecting these processes must be of necessity non-hierarchical. (Semantics is omitted from this figure, since meaning can be expressed through Grammar or Lexicon, or even through sound-symbolism, for instance gr in gr in grunt, grumble, grumpy; see Chapter 6.)

Figure 1.2 The levels of language (dynamic model)

The interactive nature of the phenomenon, of course, makes the investigation of linguistic change a matter of engaging with complexity; and this complexity might lead students of the history of English to despair of finding any generally acceptable truths on which to base their discipline. There is, in fact, a respected and respectable tradition in the linguistic sciences which holds that the only valid goal of diachronic linguistic enquiry is description, and that the discussion of causation is not a proper question for researchers to address.

These questions of complexity and explanation will be returned to explicitly in Chapter 3 and (briefly) in Chapter 9, but it is perhaps worth pursuing them a little further at this early stage since the question of causation will be pervasive in the chapters that follow. Since at least the Middle Ages a distinction has been made between a history and a chronicle: the historian aims to explain past events (and thus to sustain an argument), whereas the chronicler aims to describe the past in as neutral a fashion as possible without attempting to draw causal relationships between events. The outcome of this distinction can be seen in the practice of diachronic linguistic enquiry. Some books are essentially lists of observations, and these may be termed chronicles—not necessarily a hostile criticism, for such collections of observations are the bedrock of deeper understanding. In a sense, the notion of ‘chronicle’ correlates with the synchronic (i.e. time-independent) approach to linguistic study, in which the purpose of the discipline is to formalise the rules of a given state of language without relating these rules to their antecedents or successors; the true chronicle, with its annalistic approach, may be seen as a series of synchronic snapshots which happen to have been arrayed in chronological order, an ordering which makes no connective reference or causative link to what happens before or after. Most of the readers of this book will have already encountered such annalistic approaches, and may have even formed the impression that such chronicles are what the historical study of English is about. But this conclusion, it is held here, is wrong; the practice of linguistic historiography is to do with the interpretation of these observations, and it is historiography, not chronicle-making, which is the concern of this book.

Since this book sets out to be an historical account, it is orientated in accordance with the practice of historiography as established by tradition: it seeks answers to the question ‘why?’ through the observation of correspondences. When historians seek to account for a particular event in the past—say, the French Revolution—then they will look for its causes in the state of society within which the event took place: the financial and political bankruptcy of the monarchy, the oppression of the Third Estate, the coexistence of advanced Enlightenment ideas in France with revolution in the United States, and so on. It is by seeking to answer such questions that the discipline of history progresses, although few historians nowadays would claim to have final solutions to the questions which history poses. Similarly, the explanations put forward in this book for changes in the history of English have the validity of historiography; they are attempts to show why certain things happen when they do, argued (it is hoped) rationally from the observation of correspondences, and they are of course falsifiable, that is, open to being superseded by other explanations. Of course, it is widely accepted by scholars in many disciplines that neutral observation, the goal of the chronicle-maker, is something of a myth, for our position of observation (our point of view) conditions what is observed. Nevertheless, the disabling nature of this so-called ‘observer's paradox’ can be overstated. Observers of language can strive for neutrality on the basis of shared terms of reference, even if they necessarily fail to achieve absolute objectivity because conditioned by their own intellectual horizons. The answer to the problem is not, it is held here, to cease making observations and hypotheses, but rather to continue to make observations and hypotheses from various points of view. The question has been addressed by philosophers since at least the eighteenth century. (For a resolution of the difficulty in the terms offered here, see further Waldron 1985: 60.)

WHAT IS LANGUAGE CHANGE?

So far, language change has been discussed without further definition or explanation. Yet the question ‘what is language change?’ has to be confronted at an early stage, for, as we shall see, its definition sets the goals for our enquiry.

The distinction may be made between potential for change, implementation (itself including triggering or actuation) and diffusion. The potential for change exists when a particular speaker or group of speakers makes a particular linguistic choice at a particular time; implementation takes place when that choice becomes selected as part of a linguistic system; and diffusion takes place when the change is imitated beyond its site of origin, whether in terms of geographical or of social distribution. Strictly speaking, the first of these phenomena is not to be included as part of the typology of change. The continual flux of living languages means that new variant forms are constantly being created in a given linguistic state. However, these variants are not themselves linguistic changes; rather, they constitute the raw material which is a prerequisite for linguistic change. A linguistic change happens only when a particular variable is selected and a systemic development follows. In that sense, language change begins with implementation; when implementation of potential for change is for some reason triggered in a linguistic system, then we can speak of a linguistic change. The diffusion of the phenomenon within a particular speech-community is, it is held here, a further process which can be counted as part of the particular change involved; it may, of course, itself have further effects.

In Part II of this book, a number of linguistic events will be examined in the light of this description of change. It will be observed there that the potential for change, the set of ‘variational spaces’ within a given linguistic system, is always present. However, a particular interaction of processes—extralinguistic with intralinguistic, or intralinguistic with intralinguistic—at a particular time and in a particular place triggers the implementation of change, with subsequent diffusion of that change within and beyond a particular speech-community. Subsequently, other changes can be triggered in turn.

FORM AND FUNCTION

In pursuing the aims described on pages 3–7, two key terms will be used on a number of occasions during the course of this book; it is therefore appropriate to offer some definitions at this initial stage. These are the terms form and function. These terms are used technically in many disciplines (e.g. in architecture), so it is perhaps worth taking time to define the special ways in which they ar...