![]()

Section II

Background to Real Estate and Financial Markets

![]()

4 Real estate market mechanisms

Introduction

Real property, the land and buildings that make up the built environment we see around us, accounts for the overwhelming majority of the wealth of the UK. According to ONS (2011), i.e. The Blue Book, the total net worth of the UK at the end of 2010 was almost £6.9 trillion. Residential and commercial property accounted for almost three-quarters (£5.1 trillion) of this (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1 Assets total (ONS 2011: 249)

|

|

| | 2010 £ billion |

|

| Residential buildings | 4,260 |

| Agricultural assets | 51 |

| Commercial, industrial and other buildings | 807 |

| Civil engineering works | 790 |

| Plant and machinery | 497 |

| Vehicles (including ships and aircraft) | 193 |

| Stocks and work in progress | 244 |

| Mobile phone spectrum | 22 |

| TOTAL | 6,864 |

|

Real estate is a very complex asset to manage and it is also a complex matter to implement the technical change both to perform more sustainably and for investors to commit more sustainably. Also in functional terms, this complexity may hamper users' ability to change towards more sustainable behaviours and mindsets. This then raises important challenges for those that manage such assets either for investment or for occupation.

In order to understand both investor and occupier behaviour in relation to real estate, it is first important to have some appreciation of the nature of real estate assets. This chapter therefore provides some context for the rest of the book in terms of the importance of real estate in economic activity, the specific characteristics of real estate and the different legal interests available for real estate ownership and occupation.

Characteristics of property

Given the scale of property within the national balance sheet, as shown in Table 4.1, it is worth reviewing its particular characteristics, which distinguish it from other investable assets. This section explores these main characteristics.

Complex

The financing, construction and operation of property are complex and require a wide range of different skills at each stage of the property lifecycle. Different degrees of risk are also associated with each stage. This contrasts with the acquisition and ownership of assets such as listed securities. The complexity of property means that owners often need to have or to hire people with specialist skills to manage it. For example, property development is complex and risky. It involves coordinating a wide range of activities over an extended time period to deliver a completed product. That product has to meet the needs of both the occupational (tenants) and investment (owners) markets. The overlap between these three activities (i.e. development, investment and occupation) forms the basis of the dynamics of the property market.

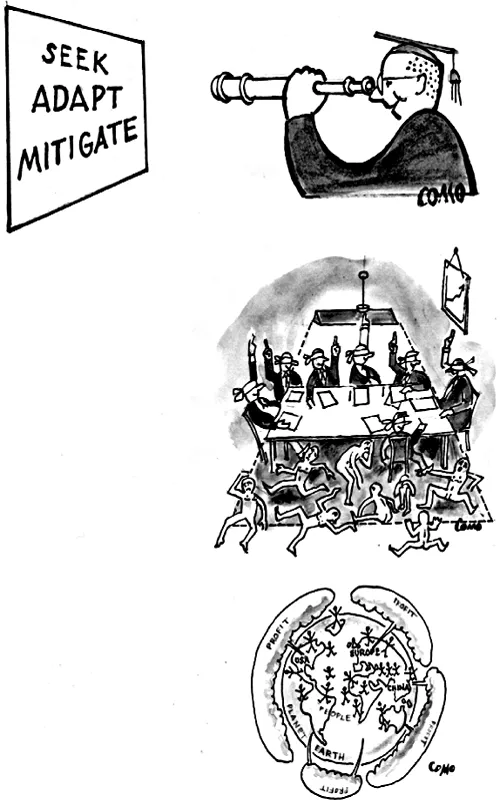

Keogh (1994) shows these three activities as elements of a simple structure of a property market, linked by the flow of information between them. In the user market, firms need to occupy a stock of buildings, the required amount of space being determined by output levels, profitability and asking rents. In the investment market, a property owner's return is the rent that they receive. The relationship between rent and return determines the price or capital value of the property. Furthermore, that capital value would affect property companies and construction firms in the development market. When capital values are higher than the cost of provision, new construction projects are undertaken, and the supply in the user and investment markets will change accordingly.

The needs of the three sectors of the market will not necessarily coincide. Occupiers will have very immediate requirements as to the suitability of the space for their business today and the near future. Investors will want a product that is lettable today (so meeting current occupational needs) but that, in their judgement, will remain lettable and also saleable (so meeting future investment market needs) into the more distant future. This often requires some difficult decisions based on a wide range of information and data. Even with professional advice, a decision maker will often concentrate on what is considered the most important information. This bounded rationality recognises human limitations in understanding complex assets and uncertain circumstances (Woffold 1985).

Heterogeneous

All properties are different. Strictly speaking, in English law, it means that all interests in property are different. It is possible for two or more parties to hold different interests (e.g. freehold and leasehold) in the same physical property. This has a number of implications for the asset class including, as already noted, greater complexity.

High transaction and operating costs

Complexity and heterogeneity also lead to higher transaction and operating costs than for listed securities. When considering the acquisition of an interest in property it is necessary to perform extensive checks of its legal and physical characteristics. This ‘due diligence’ is part of the risk management process that any prudent owner or investor will undertake. It reduces the likelihood of any negative surprises occurring after acquisition. Due diligence itself can be costly as it involves technical specialists such as lawyers and surveyors. To some extent the cost can be regarded as an insurance premium against future expenses. Whilst these costs are significant, by far the greatest cost of acquisition, in the UK but also in many other countries, is the transfer tax. In the UK this is called Stamp Duty Land Tax (SDLT) and is levied at the rate of 4 per cent on all purchases of non-residential property over £500,000. Considerable effort has been expended over the years by investors in trying to devise acquisition structures that minimise or eliminate this cost.

Transaction costs for a vendor are much lower as they do not (in the UK) pay any transfer tax and the professional fees are less as no due diligence is involved. Nevertheless, the round trip (to sell one property and reinvest in another) transaction cost is about 7 per cent.

The extent to which operating costs are an issue for the owner of a legal interest in property depend on the nature of the interest and its relationship with any other interests. As a physical structure, a building requires regular maintenance to ensure its suitable condition. In the UK, it has historically been common practice for the owner of a freehold interest to pass all of these costs onto the tenant(s). This is through the terms of the full repairing and insuring (FRI) lease. There are also operating taxes (called business rates in the UK), which are usually also the responsibility of the tenant(s).

With limited exemptions (fewer now than in the past), business rates are payable whether or not a property is occupied. In the case of a vacant property, they remain the liability of the freeholder. Under the terms of an FRI lease in the UK, the freeholder can generally expect to receive a net income (before tax) that is close to 100 per cent of the rent paid by any tenant. In other jurisdictions the position is not as favourable for the freeholder. For example in the United States it is common for a landlord to be able to recover operating costs and taxes from the tenant, but subject to caps on the annual increase. This can lead to a decline in the recovered overheads over the life of a lease. Both market practice and statute may limit the extent to which a freeholder can recover taxes and other operating costs from a tenant.

Large lot sizes

Property assets acquired as an investment are generally only available in lot sizes in excess of £100,000 and frequently very much more. This compares again with listed securities that can be bought for a few pounds. Held directly, property is therefore limited to investors with substantial finance available and, those who do not have a problem with having capital tied up in illiquid assets because ‘the accumulation process experiences uncomfortable friction when capital (i.e. “value in motion”) is trapped in steel beams and concrete’ (Weber 2002: 519).

Depreciation

Although not factored explicitly into the decision-making process of many investors or occupiers, depreciation is a very real cost that needs to be faced through the period of ownership of a property. In a rising market, it tends to be masked by the general upward movement in prices. It may suppress the income stream and the exchange price but not necessarily a building's use value (Weber 2002). Depreciation comes in a number of forms, namely: physical, functional, legal and aesthetic.

• Physical depreciation, the wearing out of a building, is the most obvious form of depreciation. It manifests itself in the periodic expenditure required to repoint brickwork or replace lifts, for example.

• Functional depreciation (also known as obsolescence) arises from the changing needs of occupiers that can no longer be met. For example, many older buildings lacked the floor-to-ceiling height needed to install air conditioning when it first became a common requirement. This made them less attractive to occupiers than either brand new buildings or even other older ones that could be retro-fitted with the equipment. This represented a permanent loss of value that could not be recovered, even with additional expenditure.

• Legal depreciation arises when the legal requirements of buildings change. In the UK, these are often reflected in changes to the statutory building codes known as the Building Regulations (see later for details). Standards are changing all the time and usually it is only new construction work that has to meet current standards. Existing buildings are not normally in a constant state of modification to meet changing standards. However this is not always the case. Disabled access regulations, for example, have become tighter in recent years and many buildings have had to be retrofitted to enable wheelchair access.

• Aesthetic considerations also play a part. Tastes change over time and building features that were once popular fall out of fashion, again leading to depreciation. Aesthetic trends towards open plan offices and a preference for better natural lighting, for example, have also left many older buildings behind. New legal requirements, such as wheelchair accessibility, can also leave older buildings at a disadvantage.

For an investor, the cost of depreciation is not always apparent until it involves cash expenditure, so it tends to be hidden. But it is a very real cost. The effect becomes clear when comparing the value of an older building with a relatively modern one with a current specification. The decision is more difficult in the case of complex office buildings and shopping centres involving high capital investment. For industr...