1 Contemporary urban space-making at the water’s edge

Richard Marshall

In an article devoted to the public realm, Peter Davey, expressing a widely held view, laments that “we have almost forgotten how to build cities” (Davey, 1999:32). This sentiment stems from a common feeling of disappointment toward the contemporary city. Today we find many articles and books that condemn the current condition of our urban environments. Everyone, it seems, is anti-city. However, the condition in which we find ourselves is not an issue of memory. We have not forgotten how cities were made, rather our ideas of what a city is and how to put it together seem at odds with the way the world works today. A nostalgia for earlier times reinforces conceptions of older models of the city. Our cities have changed faster than we have been able to adjust our thinking and because of this the contemporary crisis of public space is due to a lack of confidence in knowing what works today. Our problem is not one of memory; it is one of adjusting our ideas of what is an appropriate urban form to be in line with the current reality of our culture and society. What is needed in urban design today, above all else, is a re-calibration of our ideas to the currency of our time.

The city is becoming less the result of design and more the expression of economic and social forces. The size of contemporary urban agglomerations means that no one single authority controls the form of the city. A mixture of bureaucracy and market forces defines the form of the city. The city is a physical container of our culture and, as such, it is the expression of us. The city is a mirror of the complexity of modern life. The result is a city environment where instability is the only constant. The results of half a century of urban space-making have left us with a diffused urban structure; a city pieced together from heterogeneous elements that when combined create a homogeneous aesthetic. This amorphous city appears abstract, disordered, confused and illogical. This abstraction acts to diffuse meaningful relationships for those that live in the city and inevitably leads us to feelings of loss and a yearning for a better place, for an idealized urban environment.

It is within these present difficulties that a space has opened up in the city which allows expressions of hope for urban vitality. The urban waterfront provides us with this space. On the waterfront, we see glimpses of new city-making paradigms, partial visions for what our cities might be. If the city has come to be regarded as a reflection of society and its problems, it itself is a problem of unprecedented complexity. By focusing on the urban waterfront, we are able to isolate and view in focus specific responses to the problems of disorder and confusion mentioned previously.

Nan Ellin, exploring the idea of postmodern urbanism, notes that among anthropologists, cultural theorists, architects, and urban planners there has developed a fascination with notions of edge, a response “to the dissolution of traditional limits and lines of demarcation due to rapid urbanization and globalization” (Ellin, 1999:4). Among architects and planners, a great deal of attention is being paid to spaces considered interstitial, “terrains vagues,” “no man’s land,” or “ghost wards” (Schwarzer, 1998). Ellin states that this is apparent

in the concern for designing along national borders and between ecologically-differentiated areas such as along waterfronts… The notion that the talents and energies of architects and urban planners should contribute to mending seams, not tearing them asunder, to healing the world, not to salting its wounds, has grown much more widespread in acceptance.

(Ellin, 1999:5)

It is in the spaces provided by the urban waterfront that planners and designers wrestle with the appropriateness of their intentions for the present, and for the future.

The time in which we live is often referred to as postmodern. The rise of postmodernism, in its many forms, is a general desire to reinvest meaning into various aspects of our lives. Today, meaning is central to discussions of the city. This, despite the fact that such discussions have become so contested. The crisis of the public realm that Davey speaks of is really a crisis of meaning. What does the public realm mean in an increasingly global and fragmented world? How do we as designers accommodate multiple meanings in the design of public space? The best types of public space allow for the inclusion of multiple meanings and all levels of society. As Rowe points out, the alternatives are too often exclusive, corporately or authoritarian dominated precincts (Rowe, 1997: 35).

In the articulation of urban waterfronts, these issues are critical. The visibility of these sites means the waterfront becomes the stage upon which the most important pieces are set. In doing so, the waterfront is an expression of what we are as a culture. The urban waterfront provides possibilities to create pieces of city, to paraphrase Davey, that enrich life, offer decency and hope as well as functionality, and can give some notion of the urban ways of living celebrated by Baudelaire and Benjamin, Oscar Wilde and Otto Wagner. In these possibilities, we remember that urban development is not just for profit, or personal aggrandizement, but for the benefit of humanity and the planet as well. It is on the urban waterfront that these visions of the city are finding form. These are the sites of post-industrial city space-making.

The reuse of obsolete industrial space along the waterfront is a major challenge and an opportunity for cities around the world. Some of the most important redevelopments in recent years have been waterfront revi-talization projects: consider, for example, such projects as London’s Canary Wharf, New York’s Battery Park City, Vancouver’s Granville Island, Sydney’s Darling Harbour, or San Francisco’s Mission Bay. Waterfronts, of course, have historically been the staging points for the import and export of goods. Location next to the water was a competitive advantage to many industrial operations. The edge between city and water, between the production site and its transport basing point, was the most intense zone of use in the nineteenth-century city. Use on the urban waterfront was often exclusively port or manufacturing related. The wealth of cities was based on their ability to facilitate the need of industrial capital to access waterfront resources. However, the creation of this wealth brought with it environmental degradation and toxicity, which today characterize these residual urban spaces.

Our information-saturated, service-oriented economic systems no longer rely on the industrial and manufacturing operations of the past. Technological changes have redefined the relationships of transport and industry. The concurrent advancements of road, rail and water transport, combined with the requirements of containerization, have shifted the basing points for global water transport away from previously historic waterfronts. With this passing, the relationship between water and the generators of economic wealth has changed. Typically, these areas exist as spaces of urban redundancy, as left over spaces in the city. The use and the environmental condition of these spaces are of major concern to many cities in their revi-talization efforts.

These waterfront redevelopment projects speak to our future, and to our past. They speak to a past based in industrial production, to a time of tremendous growth and expansion, to social and economic structures that no longer exist, to a time when environmental degradation was an unacknowledged by-product of growth and profit. Through historical circumstance, these sites are immediately adjacent to centers of older cities and, typically, are separated from the physical, cultural and psychological connections that exist in every city. They speak to a future by providing opportunities for cities to reconnect with their water’s edge. Because of their size and complexity, these sites require innovative mechanisms for their consolidation. Historically the sites of industry, they now attempt to re-center activity in urban space, to reposition concentrations of activity, to shift the focus from the old to the new.

Waterfronts have been a topic of academic and professional interest since the 1960s. The success of projects such as the Inner Harbor in Baltimore spawned a series of large urban redevelopment projects on waterfront sites around the world. Waterfronts became associated with ways to recreate the image of a city, to recapture economic investment and to attract people back to deserted downtowns. Waterfront development has generated its own discipline. As Meyer notes, “professionals (and academics) from all over the world keep one another informed of the most recent developments by means of international waterfront networks” (Meyer, 1999: 13). The Waterfront Center, based in Washington, DC, Centro Internazionale Città d’Acqua in Venice, and the Association Internationale Villes et Ports in Le Havre are three examples. These networks produce their own publications and hold their own conferences. An indication of how “competitive” this industry has become is that on the same weekend in October of 1999 three waterfront conferences occurred in North America alone. These were “Waterfronts in Post-Industrial Cities,” held in Cambridge by the Harvard Graduate School of Design; “Urban Waterfronts 17,” held in Charleston by the Waterfront Center, and “Worldwide Urban Waterfronts,” held in Vancouver by Baltic Conventions from the United Kingdom.

The urban waterfront tells us many things about the way we make, and think about, cities. Projects such as the London Docklands are examples of how planning and design intentions are subverted by the concerns of power and capital (Malone, 1996: 15). Sydney’s Darling Harbour is an example of a politically driven project that circumvented city and state regulatory systems to satisfy political agendas. Some have described the project as an “ill conceived insertion of gigantic new developments” into the fabric of the city (Morrison, 1991:4). Amsterdam’s Ij-Oevers project is an example of a project that speculated heavily on global financial growth, which did not eventuate. Such projects teach us about the volatility of markets and global capital. They also teach us about the nature of building cities and how to plan for their construction. Projects such as Boston’s Fan Pier or Melbourne’s Docklands are current manifestations that deal with issues of public access and the appropriate mix of uses on privileged waterfront sites.

Large waterfront redevelopment projects often circumvent regulatory systems, and can be so insular as to deny the existence of the context into which they insert themselves. They reside in a self-imposed vacuum. However, their presence often puts pressure on existing infrastructure, on highways, and road systems. The availability of new tracts of very large land allows for programs, often at odds with the scale and grain of the traditional city, to find places to locate. These are the sites for big program facilities such as museums, exhibition halls, convention centers and sports stadiums.

There is a tendency, in much of the literature, to view waterfronts as a kind of urban panacea, a cure-all for ailing cities in search of new self-images or ways of dealing with issues of competition for capital developments or tourist dollars. The waterfront redevelopment project has became synonymous with visions of exuberance. Images of Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, or of Sydney’s Darling Harbour (or any number of others), filled with joyous masses, inspired city officials and urban planners around the world and led to a rash of “festival marketplaces.” However, the focus on the end-product of waterfront development ignores the problems, and possibilities, faced by cities as they work to create them. The idea of project-as-product combined with the spread of “architectural capital” has led to situations where international design clichés characterize the waterfronts of Boston, Tokyo and Dublin (Malone, 1996: 263). The result is a kind of rubber-stamping of the “successful” waterfront magic, often with limited results.

This type of thinking deals with such developments removed from the political structures and financial mechanisms that are fundamental to their realization. These projects, however, are born out of a process, one that involves all levels of government, significant sources of capital, various organizations and individuals that may all have competitive agendas. In the consideration of waterfront projects, one must understand the peculiarities of the contexts and their relationship to international frameworks. Only in this way can understandings from one situation be applicable as lessons to another.

The factors that have led to these waterfront opportunities are well known. These have combined to create sites of abandonment. These sites, being adjacent to water, now offer us unique opportunities. However, as Malone points out, neither the factors that have created the opportunities for redevelopment nor the processes of renewal fall outside the common frameworks for urban development. The urban waterfront is, simply stated, a new frontier for conventional development process (Malone, 1996: 2). Both the types of development and the forms of capital on the contemporary waterfront are common to other parts of the city. What makes the contemporary urban waterfront interesting is the high visibility of this form of development. The high profile of their locations means that waterfront projects are magnified intersections of a number of urban forces. Simply, the economic and political stakes (and hence the design stakes) are higher on the urban waterfront. Indeed, through changes in technology and economics and the shifting of industrial occupancies, the waterfront has become a tremendous opportunity to create environments that reflect contemporary ideas of the city, society and culture.

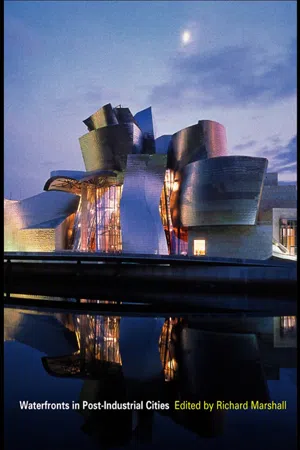

In October 1999, a group of political leaders, mayors, city councilors, heads of planning, architects, planners, and financiers, from eight international cities, met with faculty from the Harvard Graduate School of Design for a three-day conference entitled, “Waterfronts in Post Industrial Cities.” The participating cities were Amsterdam, Bilbao, Genoa, Havana, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Shanghai, Sydney, and Vancouver. The aim of the conference was twofold: to explore the challenges faced by these cities in dealing with development on their waterfronts, and to place those considerations into a larger understanding of contemporary urbanism.

Most books on waterfronts deal with a relatively narrow collection of cities and projects – London, New York, Toronto, Barcelona, etc. One might describe them as the “top ten list” of waterfront revitalization stories. Boston and Baltimore, for example, are now the stuff of waterfront redevelopment legend. Our aim in developing the conference was to explore two types of “waterfront city.” The first type of city can be found in other publications. Our aim, however, was to retell their stories to understand not only the successes but also the challenges faced by these cities – Amsterdam, Genoa, Sydney and Vancouver – in their revitalization efforts. The second type of city was much harder to determine and does not, or minimally, appear in the waterfront literature. Our aim in selecting these cities was to find contemporary examples that represent the emerging contexts for waterfront revitalization efforts – these include Bilbao, Havana, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria and Shanghai. Our intention was to move beyond the glamour of these revitalization efforts to evaluate their success, understand the challenges that were overcome, and reflect on the longer-term sustainability of the projects in social and economic terms. Our goal was also to try to uncover lessons from the first type of city that can be applied to the second type of city.

The value of the conference was that it allowed decision-makers to engage with planners and designers in a meaningful dialogue. Too often, communication between decision-makers and designers and planners only occurs after major decisions have already been made. The aim of the conference was to open a dialogue and create possibilities for more engaging and informed discussions. The conference advocated an inclusive approach that engages designers, politicians, developers, and economists. The central question for all of us is what is an appropriate urbanity as we start a new millennium. The urban waterfront is an ideal setting for these considerations. This book is an exploration of these visions.

The title of the conference and this book is worth explaining. Borrowing the definition from Savitch, post-industrialism refers to a broad phenomenon that encompasses changes in what we do for a living, how we do it, and where it occurs (Savitch, 1988). Specifically, the post-industrial city deals with processing and services rather than manufacturing, intellectual capacity rather than muscle power, and dispersed office environments rather than concentrated factories. These changes manifest themselves into the building of a new physical environment constructed specifically to meet the needs of the twenty-first century. Examining the redevelopment of the urban waterfront tells us a lot about what we as a culture believe those needs to be.

Urban waterfront developments are no different to other forms of redevelopment in the sense that they cover a broad spectrum of different scenarios. Four meditations form the structure of the book and provide a mechanism for thinking about particular aspects of waterfront redevelopment. These meditations – “Connection to the Waterfront,” “Remaking the Image of the City,” “Port and City Relations” and lastly “New Waterfronts in Historic Cities” – form the general structure of the book. A comparison of two cities frames the context of each meditation. A series of reflections follow each city comparison. The book is structured to deal both with broad issues, that might be applicable to a variety of contexts, and with specific city descriptions which outlay the current state of waterfront development in these locations.

In “Connection to the Waterfront,” Richard Marshall provides a comparison of waterfront developments in Vancouver and Sydney. The former industrial waterfront areas of many cities now exist as underutilized parcels, separated from the physical, social and economic activity of the rest of the city. In their reconsideration, these sites pose significant issues. How should that redevelopment occur? What is an appropriate form of development? What is an appropriate urban form? How are connections made between the older city and the water through these redevelopment efforts? Vancouver and Sydney provide two remarkable examples where these questions influence the production of new city space.

In Sydney, as in other cities, the connectivity of the physical fabric and the water suffered from the insertion of roads between city and harbor. This, combined with jurisdictional fragmentation, has tended to isolate major waterfront projects from the rest of the city. This is in spite of the fact that the image of the city is inextricably linked to its water. In defining the water as an urban amenity, Sydney faces such issues as the appropriateness of the waterside program and of connecting through, under or across large pieces of infrastructure.

In the 1980s, Vancouver developed the Central Area Plan to reinvent its inner city. Subsequently, the waterfront has changed from railway and industrial use to residential and recreational use. Today, stresses are emerging between integrated, mixed-use, fine-grained urban develo...