eBook - ePub

Evaluation in Schools

Getting Started with Training and Implementation

- 108 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First published in 1992. This introductory handbook provides the training materials, relevant information and guidance needed to get started on a structured approach to evaluation. In particular, Evaluation in Schools: * concentrates on a practical approach to training key personnel * offers valuable training models and photocopiable worksheets * written specially for the non-expert * includes objectives, outline programmes and workshop briefings.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralPart I

Evaluation in context

Chapter 1

In defence of evaluation

Evaluation is the process of systematically collecting and analysing information in order to form value judgements based on firm evidence. These judgements are concerned with the extent to which particular targets are being achieved. They should therefore guide decision-making for development.

The term ‘evaluation’ is sometimes used to refer specifically to the judgemental part of this process only. We have found the broader definition given above more useful, because the validity of the value judgements which can be made is greatly dependent on the nature and provenance of the data collected. In this context, the need is for practicable data collection and handling systems which provide sound evidence on which to base judgements. The primary purpose of this book is to assist schools in the task of embedding such systems in their staff’s normal practices.

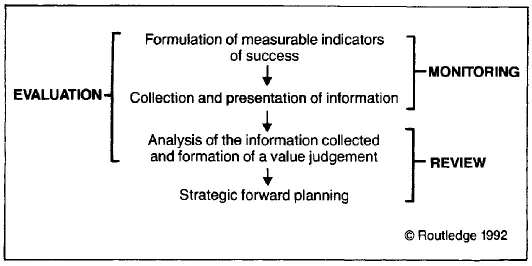

Evaluation is often set in the context of a monitoring, evaluation and review cycle (Tipple, 1989).

- Monitoring is the process of collecting and presenting information in relation to specific objectives on a systematic basis. It should always be undertaken for specific purposes if the effort involved is to be justified.

- Evaluation takes this process a stage further in that the information is analysed and value judgements are made.

- Review is a considered reflection on progress, using evaluation data to inform decisions for strategic planning.

Figure 1.1 The interrelationship between monitoring, evaluation and review

A simple model showing the interrelationship between these three activities is shown in Figure 1.1. The place of evaluation within a school’s management cycle is explored more fully in Chapter 2.

WHY EVALUATE AT ALL?

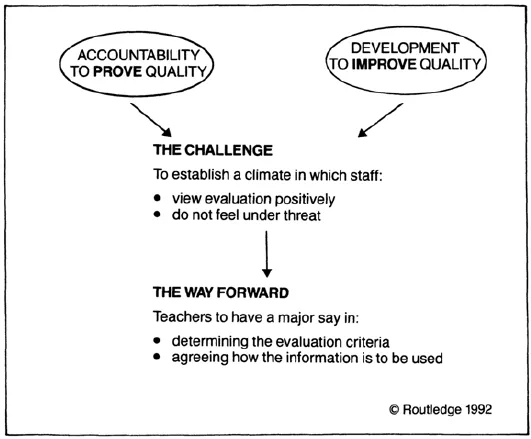

There are two main purposes for evaluation of performance:

- ACCOUNTABILITY to prove quality, for example, to demonstrate that funding is being properly deployed to maintain and improve standards;

- DEVELOPMENT to improve quality, for example, to assist in the process of improving curriculum development and delivery.

Accountability is a central thread running through most of the changes enshrined in the 1988 Education Reform Act. It has been suggested that the various school-based evaluation initiatives of the late 1970s and 1980s were, in general, disappointing because they seldom functioned as appropriate instruments of accountability (Clift, Nuttall and McCormick, 1987). However, in the present climate, school-based evaluation is more likely to take root because schools now have to provide information about their performance over a wide range of issues, and in some detail, to parents, governors and the LEA, particularly under Local Management of Schools (LMS). With the coming of the Parents’ Charter, this accountability is being brought very much to the fore and places an even greater responsibility on schools and their governing bodies, while reducing the role of the LEA.

The primary function of all this accountability is to raise standards. The Parents’ Charter states that governors will need to publish an action plan following the report of independent inspectors on the school once every four years. In the period between external inspections, schools will want to monitor the implementation of the action plan and be well prepared to meet the next full inspection. However, a major task facing any school’s senior management is that of establishing a climate in which staff view evaluation positively. This is more readily achieved when teachers have been fully consulted about the development plan and have had a major say both in determining the evaluation criteria and in agreeing how the information collected is to be used. In this way, schools can ensure that they have the data they need to aid development, and staff will be less likely to feel under threat from the evaluation. Moreover, where the parameters of the evaluation are not explicit within an agreed development plan, teachers may be uncertain about what precisely are the targets at which their school is aiming. It is less than helpful for them to be told post factum that they failed to reach these targets—the shifting goal-post syndrome. In sum, evaluation is more effective in raising standards when staff view it as having a developmental as well as an accountability focus. Figure 1.2 summarises these points.

WHY ADOPT A PLANNED APPROACH?

School managers have always had to take important and far-reaching decisions. Traditionally, they could often rely on experience to make these decisions against a familiar and relatively stable backcloth. Nowadays, however, change is the norm and crucial decisions are often required very quickly. Managers need reliable information systems to make sound decisions under changing circumstances.

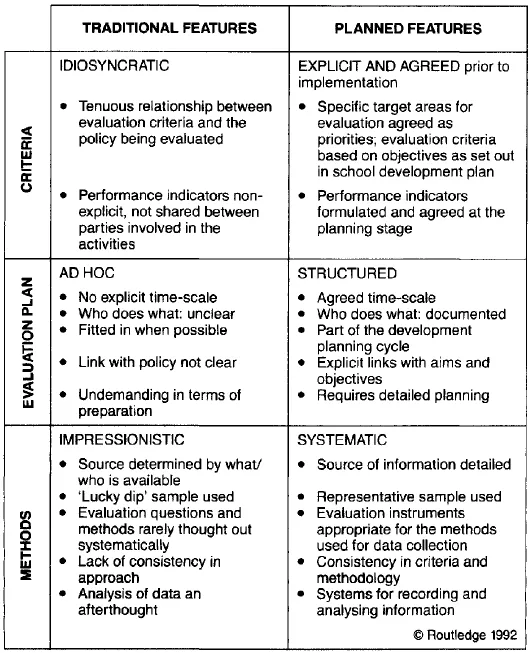

The principal benefit of using a planned approach to evaluation is that it is designed to provide relevant and reliable information on an ongoing basis to inform strategic forward planning. The planned evaluation is characterised by:

Figure 1.2 Purposes of evaluation

- agreed target areas for evaluation;

- explicitness about criteria for the evaluation of success;

- an evaluation plan which outlines who will collect the data, when, and what will be the source of the information;

- a systematic approach to the collection and recording of information where all involved use appropriate, agreed evaluation instruments.

Features of the traditional and planned approaches to evaluation are contrasted in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3 Traditional and planned evaluation contrasted

Source: Based on an original formulation by Dr Colin Morgan, Open University.

CONSTRAINTS

School-based evaluation can only succeed if it does not take up disproportionate amounts of time, effort and resources. Constraints on schools include shortage of time, lack of expertise in evaluation, and reluctance of staff to embrace evaluation as an integral part of normal practice. The following list of suggestions is offered to help ameliorate these problems:

- Limit the evaluation to a few specific focuses. Target on some specific, priority objectives which are achievable in the short term and are readily measured, rather than go for the grand plan in a single leap. For example, to increase staff and student use of IT in the National Curriculum core subjects in Years 7 and 8 is a focus for short-term development which is achievable and measurable. By contrast, to improve the quality of IT experiences for all pupils is a laudable aim but one which requires a longer time-span to achieve. Moreover, it would be difficult to measure, needing a level of sophistication in evaluation techniques which few schools would wish to contemplate.

- Collect essential information only. Be clear about what information is really necessary for the purposes of evaluation. It is all too easy to be carried away by enthusiasm and to try to collect everything under the sun about the chosen topic when a much more limited exercise would suffice.

- Make the maximum use of information already available. Before rushing into designing questionnaires, interview schedules and classroom observation checklists, scan existing sources of information such as attendance registers, room/equipment usage logs, published statistics and other data collected recently by the school. Also make maximum use of any evaluation data about the school, for example, HMI or LEA reports, and TVEI evaluation exercises.

- Keep it short and simple (KISS). If you are obliged to gather information from staff or pupils, make your questionnaire/ interview brief and unambiguous. Ask only for the information you really need. Avoid questionnaire/ interview design requiring complex and time-consuming analysis techniques. Before you collect the data, decide how you will analyse the responses.

- Make it worthwhile and credible for staff. Involve staff at an early stage in agreeing the priorities for both development and evaluation in advance. The purposes of the evaluation should then be clear and its potential value to staff in their work and concerns be explicit. The uses of the data—who has access to the information and why— also need to be agreed. Finally, the credibility of the evaluation system within a school has to be established by ensuring that:

Figure 1.4 Possible ways of overcoming the evaluation constraints

- Limit the evaluation to a few specific focuses

- Collect essential information only

- Make the maximum use of information already available

- Keep it short and simple(KISS)

- Make it worhtwhile and credible for staff

© Routledge 1992

- the outcomes are VALUABLE to all the parties concerned;

- the judgements made must be VALID, that is they must be supported by evidence;

- the process should be VERIFIABLE, that is, reasons for the judgements should be specific with the supporting evidence presented;

- the process should be VIABLE, that is, cost-effective in terms of time and resources and therefore sustainable.

Figure 1.4 summarises these ways of trying to ameliorate the constraints.

WHICH EVALUATION MODEL?

There are three critical parameters in evaluation:

- the choice of target areas and evaluation criteria;

- the control of the evaluation instruments, including data collection methods;

- the judgement of outcomes.

Figure 1.5 illustrates these three parameters and Figure 1.6 shows the range for each parameter.

The first parameter concerns how the target areas are chosen and the criteria for evaluation are set. At one extreme, these are imposed on the school by someone else. At the other, schools set their own target areas and criteria.

The second parameter deals with control of the evaluation instruments. At one extreme, the instruments, including data collection methods, are determined by an external evaluator. At the other, the school being evaluated chooses which evaluation instruments to use and how to collect the data.

The last parameter is about control of the evaluation outcomes and ranges from a closed to a negotiated judgement. A closed judgement is one where those being evaluated have no part in preparing the final evaluation ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Training Materials

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Abbreviations

- Part I Evaluation in Context

- Part II Staff Development and Instrument Design

- Part III The Way Forward

- References

- Further Reading

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Evaluation in Schools by Glyn Rogers,Linda Badham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.