![]()

1

Beyond Home Ownership

An Overview

Richard Ronald and Marja Elsinga

Introduction

Even though it forms the financial, spatial and meaningful basis of household security for most families, it was not so long ago that owner-occupied housing was considered of relatively minor significance to social conditions and economic life. Post-war policy debates, especially in European contexts, largely understood housing issues in terms of shelter and focused on the welfare of working households. This stimulated a conceptual and material focus on subsidized rental housing provision, with home ownership considered preferable for those ‘better off’. This model, however, has faded as housing, and home ownership in particular, has increasingly adopted a more central role in socio-economic affairs and welfare issues.

First, in terms of housing welfare, governments have increasingly chosen to support home ownership and to reconsider the role of social rental sectors. This manifested in a drive to extend owner-occupied housing across the developed and developing world, largely by improving borrowing conditions, and consequently debt. Explicit state support of private home buying also intensified while funding for, and the role of, social rental housing has largely been residualized. Second, housing market booms, particularly the global boom that dominated the nascent years of this century, intensified the integration of housing markets with global economic and micro-household circuits of finance, reinforcing conceptions and uses of homes as market goods. To some extent the former and latter developments reinforced each other, with escalating state sponsorship of, growing demand for and intensified capital flows into owner-occupied housing. Crises in international housing markets in the late 2000s related to major failures in US subprime and mortgage securitization systems have, however, exposed the flaws in this model and been at the heart of the ongoing global economic crisis of the 2010s.

This book addresses inherent as well as emerging features of home ownership systems in order to look into and beyond the crumbling framework of the most recent housing epoch. Furthermore, it sets out to do so in international contexts both including and beyond the English-speaking homeowner societies that dominate debates on owner-occupied housing markets. Our concern is the broader impact of tenure systems and their ongoing influence on the structure and restructuring of society. While various social, economic and political issues are addressed, the changing relationships between home ownership and welfare relations as well as the reshaping of social inequalities are of particular concern. On the one hand, recognition of home ownership as a means to enhance household welfare capacity has advanced in recent years, but has manifested and impacted each society differently. On the other, the uneven growth of housing markets and housing prices, both spatially and temporally, has shaped particular distributions of wealth and debt between different tenures and dwellings, and across different generations of homebuyers and homeowners.

One of the main purposes of this volume is to elaborate on the significance of housing as a key dimension of social change and its centrality in socio-economic relations. In the emerging post-crisis context in which this book has been composed, it appears that, whereas it was once overlooked in socio-economic and academic analyses, housing, and home ownership in particular, has become central to the structure of international finance; the governance of national economies; the restructuring of welfare states; and the security, prosperity and well-being of individual households. This chapter sets the stage for what is to come in terms of the theoretical as well as empirical analyses, both national and international. It begins by assessing the growing influence of owner-occupied housing systems before going on to explore how and why this tenure has both expanded and become so influential in macro-and micro-socio-economic affairs. The reshaping of social inequalities as well as the neo-liberal restructuring of modes of welfare provision are further addressed. The last part considers emerging housing and welfare conditions and what lies ahead in the rest of this book.

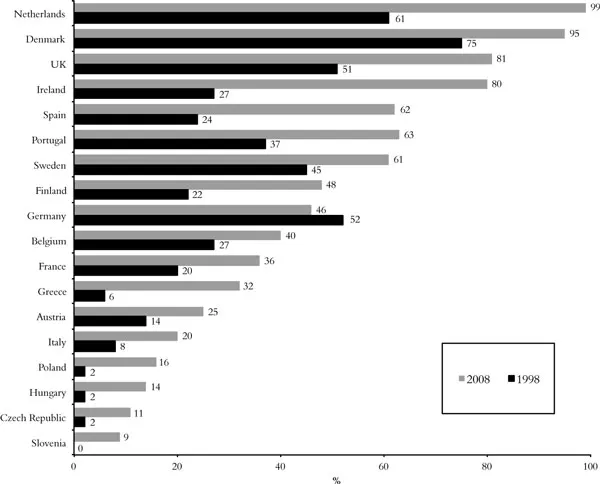

The Dominant Tenure

The growth in owner-occupied housing sectors in recent decades has been quite remarkable. In Eastern European countries in particular, home ownership grew rapidly as a result of the post-communist transition in the early nineties, with housing privatization seen as a means to accelerate free market capitalism. Public housing was typically privatized, usually via sell-offs to sitting tenants at giveaway prices. Some of these countries now have home ownership rates of over 90 per cent. Compared with these societies, growth in home ownership in countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom has been modest but is still substantial. In 1970, home ownership accounted for just half of housing in England and 63 per cent in the United States, but went on to reach around 70 per cent in both countries by 2005 (although it has subsequently begun to ebb). In Western Europe, too, although much later, many societies that developed large social rental housing sectors in the post-war decades went on to experience a rapid shift towards owner-occupation as well as substantial augmentations in aggregate mortgage debts. The Netherlands is particularly illustrative, with home ownership increasing from around 45 per cent of housing in 1990 to 56 per cent by 2006. With time, this market transformation became more intense, with the ratio of mortgage debt to gross domestic product advancing from 61 per cent to almost 100 per cent between 1998 and 2008. Across Europe, home purchase and borrowing for home purchase ballooned. By 2007, more than 60 per cent of households of the original 15 EU member states were homeowners and total mortgage debt had reached €13 trillion (Doling and Ford, 2007).

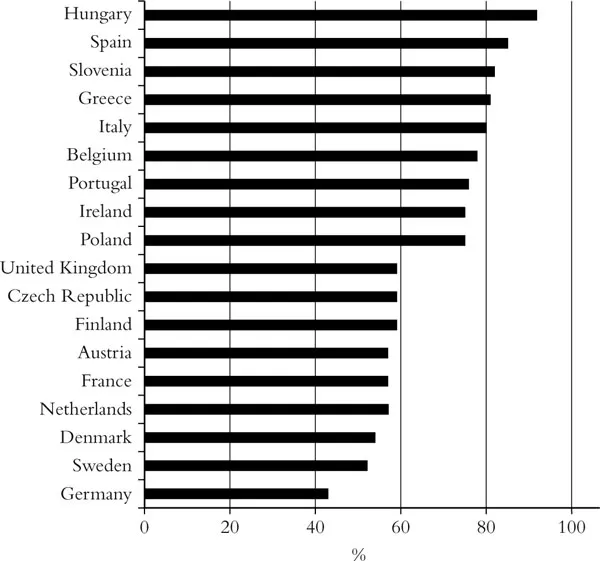

The proportionate rise in mortgage debt in European contexts is represented in Figure 1.1, while national differences in the size of owner-occupied housing sectors are outlined in Figure 1.2. The shift towards home ownership was not limited to Western societies and featured centrally in, among other places, the economic strategies of newly developed economies. In developed East Asia, growing owner-occupancy rates accompanied rapid industrialization and urbanization in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. Singapore is iconic in this regard (Chua, 2003), with the public home ownership programme, which houses over 80 per cent of all households, helping push the sector from 29 per cent to 92 per cent of all housing between 1970 and 2000. In China, where massive private housing construction and house price increases are still under way, the transformation has been seismic (see Wang and Murie, 1999; Ye et al., 2010). While urban home ownership grew under market reform measures from 17 per cent to 45 per cent between 1985 and 1997, since 1998, after abolishing work-unit housing, owner-occupation has reached over 82 per cent among urban households.

Figure 1.1 Changing aggregate mortgage debt to gross domestic product ratios for selected European countries.

Source: Adapted from EMF (2009).

Figure 1.2 Share of home ownership, as percentage of housing stock, for selected European countries.

Source: Adapted from EMF (2009).

A fundamental outcome of the super-rapid rise in housing commodification and, subsequently, market prices in these societies has been the emergence of massive affordability gaps, with intense price increases cutting younger households off from the housing market. Some East Asian societies, such as China, Hong Kong and South Korea, are now in the process of either developing or reinforcing existing social rental housing initiatives (Ronald and Chiu, 2010). Transition economies too are beginning to readjust housing policies in order to reduce macro-economic dependency on housing and construction sectors, and household vulnerability to market volatility. Yet even in the face of these experiences in the East, as well as market failures currently evident in most Western societies, the expansion of owner-occupied housing sectors as well as market deregulation continue to be a policy prescription – promulgated by agencies such as the World Bank and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) – for developing societies.

So what has been behind the spectacular and widespread orientation towards home purchase in recent decades? Economic approaches have traditionally emphasized global convergence, associating increases in home ownership with growing levels of national affluence (see Schmidt, 1989). However, the growth in home ownership has been far from even across affluent societies and in many, such as Sweden and the Netherlands, social rental housing continued to dominate policy until the 1990s. Furthermore, the correlation between national wealth and home ownership is far from linear, with, in Europe, for example, Germany1 and Switzerland having the lowest rates – around 36–45 per cent – and Romania, Bulgaria and Albania the highest, with 90 per cent or more.

The expansion of owner-occupied sectors has been connected with the features of welfare regimes, although relationships are not always direct (Hoekstra, 2003; Kurz and Blossfeld, 2004; Norris and Domanski, 2009). Welfare regimes are understood to be the result of interclass alliances and power conflict resolutions in each society that lead to discernible relations between the state, economy and institutional structures (Esping-Andersen, 1990). In very simple terms, where labour is more influential, de-commodified forms of welfare provision – such as social housing – tend to be large, whereas where capital wins out, the welfare state is likely to be smaller and more commodified. Developed societies can be classified into three different types of welfare regime: social democratic societies with an emphasis on de-commodification; liberal ones emphasizing commodification; and corporatist countries where civil society plays a key role and where conflicts between left and right lead to contingent compromises in public provision. There are also countries where the state is considered less significant than the family in the provision of welfare (see Esping-Andersen, 1999).

In terms of housing systems, regime approaches would assume that liberal regimes, such as the United Kingdom and Ireland, and South European familyfocused regimes, such as Italy and Greece, support large owner-occupied housing sectors, as is the case. However, in social democratic and corporatist regimes the relationship is far less obvious. For example, whereas both Belgium and Germany are considered corporatist conservative in terms of welfare regimes, Belgium is decidedly home ownership orientated (around 75 per cent of housing) compared with its neighbour. Norway is another good example and, although some indicators mark it as social democratic, around eight out of ten households are owner-occupiers, many of whom have been supported by tenure-biased policy measures.

Home Ownership as a Social Project

Although variation in demand, supply and the availability of inputs such as land are usually emphasized (see Fisher and Jaffe, 2003), home ownership has grown most rapidly in each national context, albeit usually sustained by periods of economic growth, as a result of government support that has undermined the advantages of renting vis-à-vis buying, often through the subsidization of the market. In recent decades this has been evident in the European context as home ownership rates have advanced markedly in social democratic and corporatist societies that historically supported social rental housing but increasingly pursued privatization and deregulation policies. Atterhög’s (2005) comparative analysis illustrates that the policy stimulation of home ownership has worked particularly well in non-Anglophone countries, whereas the limits of home ownership seem to have already been reached in the English-speaking societies. It is, however, not only policies favouring home ownership but, it seems, also those that change rental conditions that can really make a difference.

For example, rent and tax policies help facilitate private renting in countries such as Germany, Austria and Switzerland (see Lawson, 2010) where the rental sector continues to dominate urban housing markets. In the Netherlands and Sweden, on the other hand, governments have withdrawn support and funding for social rental housing and in some cases pressured housing associations to sell off their stock (Boelhouwer, 2002; Turner and Whitehead, 2002). There has been a marked shift in the role of social housing across European countries towards servicing the needs of the socially marginal rather than the needs of regular working households (Lévy-Vroelant, 2011). As the flow of public funds into social housing has receded, the overall pattern has been that subsidies for private housing2 have expanded.

Providing opportunities for households to buy their own home has increasingly been embraced by policy makers who have pursued the proliferation of home owning, perceived as a means to spread wealth and financial responsibility throughout society. Increased home ownership has been seen as a means to improve neighbourhoods, the value of property and even the economic conditions of the poor (Retsinas and Belski, 2002).

Large-scale tenure transfers have become a common strategy among societies seeking to stimulate far-reaching socio-economic and political transformations. The ‘right to buy’ given to British social housing tenants under the Thatcher government – accounting for 1.8 million new homeowners between 1980 and 2000 – is emblematic in this regard (see Forrest and Murie, 1988). The massive transfers of East European housing stock from state to individual ownership during the post-communist transition of the 1990s also mediated a reorientation of households towards their homes in terms of asset accumulation and market relations (Clapham et al., 1996; Tsenkova, 2009). This was also a symbolic step for transition governments and marked the commodification of housing goods, the establishment of a housing market and the unburdening of the state of onerous responsibilities for housing maintenance and provision.

Extending access to home ownership has meant that increasing numbers of vulnerable or marginal households have been drawn into the tenure, helping push up prices and the cost of market entry. As rates of home ownership have expanded and values increased – making getting ‘on the ladder’ ostensibly more urgent – the more homebuyers have had to extend themselves. In the late 1990s and 2000s, with new flows of capital derived from non-traditional sources such as capital markets, banks became increasingly active – with encouragement from most governments – in lending to those who would have previously been excluded from owner-occupation. Such marginal homebuyers may well have felt that they benefited from steep price increases. However, during market downturn, which has typically accompanied trouble in the wider economy, they have been the most vulnerable to changes in lending conditions, unemployment and even family breakdown, leading to the loss of the home. Long-standing homeowners with substantial equity are often able to weather turbulent markets while those who buy at the peak of the housing price cycle with the highest loan-to-value ratios – typically younger, lower-income buyers – are usually the ones who pay the highest price (Bootle, 1996). In the United States, mass home foreclosures have characterized the most recent downturn3 and have been particularly concentrated among the most marginal homebuyers, particularly among African American and Latino communities (see Bocian et al., 2010).

A feature of public discourses on home ownership has been an association between owner-occupied tenure status and improved citizenship. In this sense, too, increasing home ow...