eBook - ePub

Making People-Friendly Towns

Improving the Public Environment in Towns and Cities

This is a test

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Making People-Friendly Towns explores the way our towns and cities, particularly their central areas, look and feel to all their users and discusses their design, maintenance and management. Francis Tibbalds provides a new philosophical approach to the problem, suggesting that places as a whole matter much more than the individual components that make up the urban environment such as buildings, roads and parks. This informative book suggests the way forward for professionals, decision-makers and all those who care about the future of our urban environment and points the reader in the direction of a wealth of living examples of successful town planning.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Making People-Friendly Towns by Francis Tibbalds in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Decline of the Public Realm

We have reached a stage in the development of our technology where we have the power to create the environment we need or to destroy it beyond repair, according to the use we make of our power. This forces us to control this power. To do this, we must first of all decide what we want to achieve. And this is far from easy….

Sir Ove Arup: How Do You Want to Live?

The need to care about the urban environment has never been greater. Towns and cities over the centuries must surely rank as the greatest achievements of technological, artistic, cultural and social endeavour. The public realm is, in my view, the most important part of our towns and cities. It is where the greatest amount of human contact and interaction takes place. It is all the parts of the urban fabric to which the public have physical and visual access. Thus, it extends from the streets, parks and squares of a town or city into the buildings which enclose and line them.

I want to suggest, however, that the public realm in many countries is under threat and never more so than in the last decade. Great Britain, for example, used to be acclaimed for leading the world in civilized urban living—in transport, housing, health and culture. It had a very rich public domain.

Yet we are now witnessing a serious decline of this rich domain. Many of the world's towns and cities—especially their centres—have become threatening places—littered, piled with rotting rubbish, covered in graffiti, polluted, congested and choked by traffic, full of mediocre and ugly poorly maintained buildings, unsafe, populated at night by homeless people living in cardboard boxes, doorways and subways and during the day by many of the same people begging on the streets. Developers and owners gate their developments. They exclude the public from shopping centre malls and street level office atria at evenings and weekends. Most new buildings do not say ‘Come in…welcome’. they say ‘Sod off…go away!’. Buildings and cities, have, to many, become little more than vehicles for making money. It needs to be recognized that the simple pursuit of profit and economic growth is not usually compatible with improving the quality of our urban life-style.

At the same time that the public realm has declined there has been a corresponding flourishing of the private realm—with an emphasis on privacy, retreat, personal comfort, private consumption and security. Looking after ‘me first’, in a rather nasty thing called the ‘enterprise culture’. The public realm is an SEP (for those unfamiliar with Douglas Adams—someone else's problem).

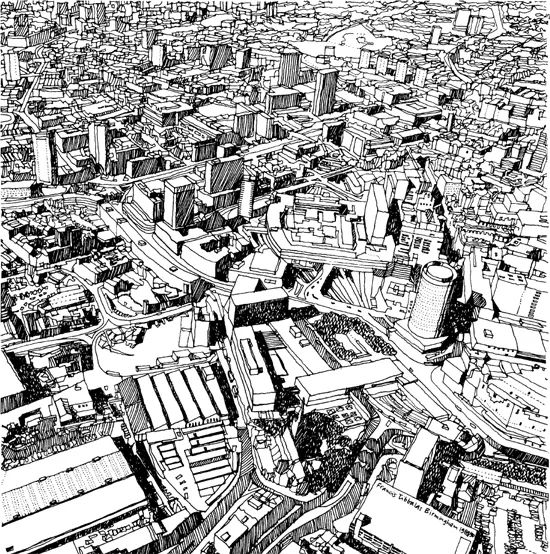

It does not matter where this actually is. It exempli-fies a city centre which underwent rapid change in the 1950s and 1960s in terms of unprecedented built development and highway construction. It offers a physical environment which now falls far short of current public aspirations.

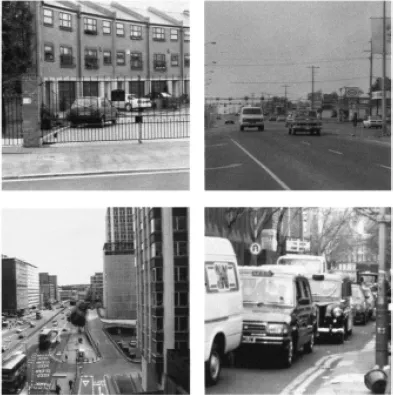

Similarly, it does not matter where the photographs used to illustrate this chapter are taken from. Collectively, they illustrate the decline and neglect of the public environment which is taking place in many towns and cities around the world, largely as a result of poverty of imagination, lack of caring and under-investment of resources.

One sees this selfish attitude epitomized nowhere more cogently than at the now crudely gated entrance to Downing Street. Under our very noses, the former British Prime Minister got away with privatizing one of the most famous streets in the world! And in many places private house developers are following this appalling example and gating their developments to make exclusive, protected enclaves.

Many private developments are now gated. Towns and cities are losing their identity and becoming drab traffic-oriented, tower-block dominated places that are the same all over the world.

Against this dreadful background, public interest in and concern about the built environment has never been greater. In Britain this is partly as a result of the outspoken views of His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales. And, it would appear, the problems of London and Britain can be found in many towns and cities around the world—including those in North America, Europe and Australasia.

Taking an overview of urban areas can certainly be a depressing experience. In many cities, particularly European ones, the centres are characterized by an appealing maze-like, intricate quality, in which sit—sometimes comfortably, at other times less so—one-off edifices left by Church, State, industry or commerce. The peripheries are usually typified by rather dull and soul-less residential suburbs. Inner areas display bleak, decaying blocks of flats and slum properties. The whole urban area is beset by dirty, noisy traffic congestion and quite probably is cut through with crude urban motorways, which have had a devastating impact on the local environments through which they pass. The better endowed towns and cities in Europe have received the benefit of considerable investment in their heritage, making them ever more attractive to tourists and a monoculture of hotels, restaurants, cafés, chic shops, and various themed experiences—a sort of ubiquitous Disneyland.

Four-fifths of Europeans live in towns and cities. Car ownership is rising. Places are losing their individuality. It is all too easy for a city to destroy its heritage and lose what is unique to it, in favour of a car-oriented, tower-block dominated place that can be seen anywhere in the world. Urban areas are sprawling and land uses are separated in a manner that makes the provision of transport facilities difficult and expensive. Some cities are even without proper government.

New development is often bland and mediocre. Cynicism at the plight of our cities was succinctly caricatured by Miles Kington, writing in The Independent in July 1988 and explaining Offbeat England to tourists:

‘Is a city a town with a cathedral?’

‘No, A city is a town with a high-rise car park blotting out the view of the cathedral. Other features of a city include a branch of Laura Ashley, a twinning operation with more than one foreign town, a railway station inconveniently far from the centre, a local evening paper which hasn't sold out by 3pm, a football team which hopes to get back into the First Division, a local radio station playing the same American records as everyone else, branches of all the main clearing banks plus one other, at least two concrete overpasses, a taxi rank with more than five cabs waiting and a ring road. On the ring road you will see signs to the City Centre. If you follow these, you will eventually end up in a cul-de-sac behind the cinema. Nobody knows why’.

I'm sure readers will recognize it!

The sobering fact of the matter is that most urban areas have become a mess, they are not people-friendly and over the past few decades, albeit with the best intentions, we have only succeeded in making the situation incomparably worse. We need a fresh look at what really matters to people who use urban areas. We need to look at urban areas as a whole and not as a series of unrelated, but competing, sectoral interests. Most of all we need the commitment of the inhabitants and users of cities and towns. They must be interested not just in creating commercial viability, tourist attractions, livability, sustainability, greenness or any of a dozen, trendy epithets now being applied to urban areas, but they must shout loudly ‘we want a better quality of life for the city as a whole’ and commit to achieving this.

So how can we improve the design and maintenance of a public realm which is currently so starved of imagination and resources?

The thrust of the book is simple and non-negotiable: The achievement of good design must be a fundamental objective of the planning system and development industry. I am broad-minded about how this might be achieved.

Shops and shopping have had a particularly devasting impact on many towns and cities—from the banal fascias and huge, bland glazed display areas which bear little relationship to the building in which they are set, to the ubiquitous indoor shopping mall, out of town centre and one-off cash and carry facility—all of which exhibit generally mediocre standards of design.

Urban designers deal in dreams, or visions. They need all sorts of tricks up their sleeves to implement those visions or to persuade others that they are worth implementing. Codes and Rule Books can be part of the tools of trade of the urban designer, but only part. We must be careful not to make everything too prescriptive—too neat and tidy. Urban areas are messy and complex, rich and muddled. The process of urban design needs to leave room for messiness and complexity! Sir Paul Reilly asserted:

There is in all city dwellers a built-in requirement for the three H's—higgledy-piggledy, hugger-mugger and hullabaloo. Anyone walking round the new city centre of Plymouth at nine o'clock at night will appreciate the gloomy absence of these qualities.

My starting point is that design is not something rather superficial, added when everything else is decided. The dreadful phrase aesthetic control does, I'm afraid, conjure up exactly the wrong impression. I am sure that readers will know the story about the aftermath of a hurricane in the United States. An anxious chairman of a major retailing development company called the manager of a shopping centre which lay right in the hurricane's path to enquire what the damage had been. ‘The buildings are fine’ he was told, ‘but the architecture's got blown away’. That is the problem! Too many people regard design as some kind of magic dust that you sprinkle on at the end, when all the really important things are decided. A bit of patterned masonry here…a few dormer windows and pitched roofs there…some trees and bollards…and the ubiquitous wall-to-wall red brick paving. This is happening everywhere. Good design has a lot more substance than that—it is about the entire physical make-up of the public realm and its subsequent care and management. Urban design is not a magic dust that can be sprinkled on to make everything look okay: it is an integral part of the planning and management of an area.

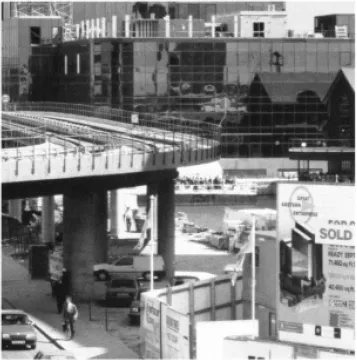

What has happened in London during the 1980s epitomizes the problem. I at once acknowledge that there are many good, or potentially good, things happening in London, at places like King's Cross, Broadgate, Covent Garden, Charing Cross, the South Bank, and many more, where a few enlightened developers are working with imaginative architects, urban designers, artists and craftsmen to produce better, more popular development. My concern is this: when you consider the public environment of Greater London as a whole, these schemes, despite the size of some of them, are not enough to rescue London.

If you want to see what, left to its own devices, the private sector produces, one need look no further than the Isle of Dogs in London's Docklands. The British Government's flagship of Enterprise Culture Development and the urban design challenge of the century adds up to little more than market-led, opportunistic chaos—an architectural circus—with a sprinkling of postmodern gimmicks, frenzied construction of the ghastly megalumps of Canary Wharf and a fairground train to get you there. It is a disappointment to residents and workers. There was a necessary intermediate step between balance sheets and building, that got missed in the rush. It is called ‘urban design’.

Left to its own devices, the private sector does not usually produce people-friendly environments, as the opportunistic chaos at the Isle of Dogs in London's regenerated Docklands demonstrates only too well.

Both political commitment and public investment are required. Ministers are rarely persuaded that there are votes in design or a good environment.

I cannot escape the conclusion that politicians have not got their priorities right in terms of our long-term needs. I also conclude that considerable public investment is urgently required to complement what the private sector is prepared to do.

And, where does the activity of town and country planning fit? Prof...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Foreword by Terry Farrell

- 1 The Decline of the Public Realm

- 2 ‘Places’ Matter Most

- 3 What are the Lessons from the Past?

- 4 Mixing Uses and Activities

- 5 Human Scale

- 6 Pedestrian Freedom

- 7 Access for All

- 8 Making it Clear

- 9 Lasting Environments

- 10 Controlling Change

- 11 Joining it all Together

- 12 A Renaissance of the Public Realm?

- Postscript

- Afterword by Kevin Murray

- Bibliography

- Index