Chapter 1

Towards a philosophy of human learning

An existentialist perspective

Peter Jarvis

Any understanding of human learning must begin with the nature of the person. The human person is body and (and at this point philosophers differ!) mind, self and soul – or some combination of them. However, human beings are not born in isolation but in relationship, so that it is false to assume that individualism per se lies at the heart of individual learning. Since ‘no man is an island’ so the human person and human learning must always be understood in relationship to the wider society. It is in relationship – in the interaction of the inner person with the outer world – that experi- ence occurs and it is in and through experience that people learn. Experience itself is a complex phenomenon since it is both longitudinal and episodic, and the latter relates to levels of awareness, perception, and so on.

It is this philosophy that we try to capture in this book: chapters cover a very wide range of different academic disciplines, all try to throw light on the very complex processes of learning. Perhaps one of the major lessons we can learn from this exercise is not only that every chapter is an over-simplification of the reality: even combined they still do not capture the complexity of this taken-for-granted process. Human learning is the preserve of no single disci- pline; definitions that fail to recognise it are incorrect, and governmental and inter-governmental policies about lifelong learning that do not include refer- ence to the whole person are incomplete and do not do justice to the whole.

This chapter offers a philosophical understanding of these processes and one that illustrates that thinking emanating from the work of Descartes is misleading. Thereafter, we explore both physical and social perspectives on learning, examining both the physical and the individual/social aspects of human living.

A philosophical basis for learning

The human being is the existent, but the essence of humanity lies in what emerges from the existent and the process of emerging is driven by the outcomes of that interaction between the inner and the outer. Human learning – the combination of processes whereby the human person (knowledge, skills, attitudes, emotions, values, beliefs and the senses) enters a social situation and constructs an experience which is then transformed through cognitive, emotional and practical processes, and integrated into the person’s biography – is the driving force behind the emerging humanity, and this is lifelong. Human beings are, therefore, both being and becoming, and these are inextricably inter- twined, since growth and development in the one affects the growth and development of the other. Learning is, therefore, existential and experiential. An experiential model of learning will be presented in this chapter (based on empirical research and subsequent reflection). It will be analysed and some of the implications of this approach, including the idea of developing multiple intelligences and the hidden benefits of learning, discussed.

We all frequently hear teachers saying, ‘I teach philosophy’ or ‘I teach sociology’, etc. It is an easy thing to do, especially as this has become a taken-for-granted form of educational language. But we do not do this! We teach students philosophy or sociology. On the surface this might appear a trivial correction, almost to the point of pedantry, but it is actually far from being of no consequence since it reflects a fundamental difference in philosophies and, for our purposes, the philosophy of learning. In this chapter, I first want to explore this philosophical basis for learning; in the second part I intend to discuss briefly my own ongoing research into human learning, and in the third section I want to illustrate an existentialist perspective on learning.

‘I teach philosophy’ puts the academic discipline at the centre of the discussion – it puts knowledge at its heart and the purpose of education is seen fundamentally as learning academic knowledge. This reflects a Cartesian philosophy which, ultimately, led Descartes to argue that ‘I think, therefore I am’, whereas I want to argue that it is the person who is at the centre. There are many weaknesses in the Cartesian position, such as we only are when we are thinking, and so on, and yet it has persisted as the most fundamental starting point for a great deal of Western philosophy. In the Cartesian argument, existence is objective, proven by thought. It is as if knowledge is objective, a finished product, out there to be acquired and, therefore, something that can be transmitted (even sold) to others. It is as if the mind were separate from the body and the sole recipient of information. However, at the very least, the person consists of body and mind, but these are not separate or distinct entities, as Ryle (1963) so forcefully argued many years ago and as neurological research has more recently verified (Greenfield 1999), and which is discussed later in this book. Mind, as this research indi- cates, is a construct illustrating the cognitive content of the neurological activities that brain research has demonstrated. As such it does not exist, but the brain does. Mind in some way transcends brain and enables us to know ourselves as persons, in relation to the external world. Body and mind are at least an internal dualism in relation to the external world, as Marton and Booth (1997: 122) have suggested. By contrast, it is the Cartesian dualistic philosophy which is rejected here.

It is also quite significant that while there have been many books about the philosophy of education and even the philosophy of adult education there have been far fewer about the philosophy of learning. By learning here I want to emphasise the process of learning and not the way that the term is used contemporaneously in such phrases as ‘adult learning’ and ‘lifelong learning’. Nevertheless, it is perhaps surprising that there are so few books since we are said to live in a learning society. However, there is one notable exception to this: Winch (1998) wrote The Philosophy of Human Learning. Significantly, he started his study (pp. 1–2) with four laudable aims:

- • He wished to rescue learning from the social sciences and to defend its distinctive philosophical perspective.

- • He wished to challenge many of the dominant ideas about learning.

- • He was concerned to explore those aspects of learning commonly neglected, such as religion and aesthetics.

- • He wanted to emphasise the social, practical and affective nature of human learning.

Clearly his concerns are very valid, especially when we recognise how learning has wrongly been regarded as falling within the domain of psycho- logical study, which is itself based on Cartesian dualism. Additionally, he was concerned that the insights of Wittgenstein should not be lost to our understanding of this human process. Almost predictably, however, he began his study with a look at Descartes and the empiricists, all of whom start with ‘the solitary individual as the source of knowledge’ (Winch 1998: 12), and thereafter he explored other historical philosophers. In a sense, he appears to be seeking to reform a contentious approach rather than to look at other schools of thought which might have been more promising to his enterprise. However, if we do not start here with trying to prove our exis- tence, where do we start? Trying to prove our existence is a rather circular argument and one which is in some ways solipsistic. But we know that we exist – this is a matter of given-ness – which is a better starting point for this discussion, and so Macquarrie (1973: 125) suggests that we might turn the Cartesian dictum around and argue that ‘I am, therefore I think’. Macquarrie (ibid.) goes on to write:

But what does it mean to say, ‘I am’? ‘I am’ is the same as ‘I exist’; but ‘I exist’, in turn, is equivalent to ‘I-am-in-the-world’, or again ‘I-am-with- others’. So the premise of the argument is not anything so abstract as ‘I think’ or even ‘I am’ if it is understood in some isolated sense. The premise is the immediately rich and complex reality, ‘I-am-with-others- in the world’.

In fact this is a similar starting point to one that Macmurray (1991) worked out very carefully when he came to the conclusion that we know about our own existence by participating in it. It is action that lies at the heart of our knowledge of our being – we are agents in relation to others. For him (p. 27), therefore, the premise begins with ‘I act’ rather than ‘I think’, or in other words, ‘I do, therefore I am’. Macmurray (p. 86) goes on to demonstrate that ‘knowledge is the negative dimension of action’ – the positive one being the development of the self as agent. In other words, underlying every action is knowledge and actors cannot separate their behaviour from their knowledge about it.

The knowledge which is involved in action has two aspects, which corre- spond to the reflective distinction between means and end. As knowledge of means, it is an answer to the question, ‘What, as a matter of fact, is the means to a given end?’; as knowledge of end, it is the answer to another question, ‘Which, of the possible ends, is the most satisfactory end to pursue?’ This second question is concerned with value, not with matter of fact. It initiates a reflective activity which seeks to arrange an order of priority between possible ends. Action itself involves the integration of these two types of knowledge. To act is to choose to realize a particular objective, in preference to all other objectives, by an effective means. In reflection, however, these two questions are necessarily separated, because they require two different modes of reflective activity for their solution.

(Macmurray 1991: 173)

This is also a point made very forcibly by Ryle (1963: 50) when he argued that when a person is doing something:

He is bodily active and he is mentally active, but he is not being synchronously active in two different ‘places’, or with two different ‘engines’. There is the one activity, but it is one susceptible of and requiring more than one kind of explanatory description.

To separate mind from body, and therefore from action, is a false dualism; indeed, in experiencing the world we are both doing something and thinking about it. Experience is a personal awareness of the Other, which occurs at the point of intersection between the inner-self and the outer world, and it is through experience as a result of being an agent that we both grow and develop. For Macmurray, an isolated agent is self-contradictory. Persons exist only in relation to others: there could be no birth without the parents, no growth without human interaction, no self without others. Individual experience is always with that which lies outside of the self. It is in interaction with the Other that I am. In other words: I do, therefore I am. In my doing, that is being an agent, I am a person.

However, there is at least one other significant factor that needs consider- ation: when we are agents, there is a combination of thought and movement, and when we are thinking about our actions we are thinking about the future – planning, envisaging – yet when we think about what has occurred we are still doing but we are also reflecting, or analysing the past. While this might also appear obvious, it is epistemologically very significant. Rarely when we are planning an action, or when we are carrying it out, do we think that we need a little bit of philosophy, a little bit of psychology, sociology, and so on. No, our thinking is in the form of everyday, or practical, knowl- edge – integrated and without academic disciplines – and when we plan that action we reflect upon previous experiences and the memories we have of them, and what we did in those situations. However, if we want to analyse events, then we might employ different perspectives or academic disciplines to show a consistent and sustained process. In a recent book (Jarvis 1999) I argued that theories, especially those arising from the study of facts and events, are always post facto, and can never be applied to future events since each event is unique and can never be repeated within the processes of our experience. In some ways, analytical reflection within the framework of academic disciplines is always about the past or a present phenomenon about which we are thinking, and not about planning for the future. Nevertheless, we can and do learn from this analysis. But it is in initiating action with the world, experiencing it, that we are – and it is from this that we can learn. Consequently, we are both being and becoming. Even so, this discussion about self-development and thought and action points us very clearly in the direction of the processes of human learning, and it is to these that I want to turn now.

The process of human learning

From the above discussion we can begin to understand why knowledge, which has been regarded as objective truth, could be taught and learned, so that ‘I teach philosophy’ or ‘sociology’ and so on – objective knowledge – makes sense within a Cartesian dualism, where the mind is distinct from the body. Here the learner is a passive recipient of an objective phenomenon and the body need not be considered within the process. But this is a posi- tion which needs now to be rejected. When we experience the outer world, the Other, we are doing so with both mind and body. When we experience, we are doing as well as thinking – our body is affected as well as our mind. Through experience we are aware of both ourselves and the Other as differ- entiated from us.

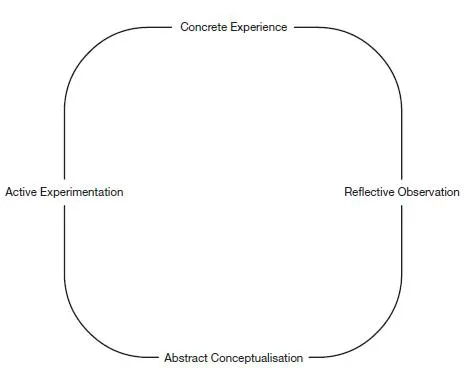

There are many theories of human learning which have been summarised in a number of books (see Jarvis et al. 2003; Illeris 2002) and in the following chapters of this book. But in traditional studies of learning two theories stand out in relation to the above discussion: behaviourism and experientialism. From the time of Pavlov, it has been recognised that learning is associated with behaviour. Indeed, Borger and Seaborne (1966: 14) suggested that from a behaviourist perspective, learning is ‘any more or less permanent change in behaviour which is the result of experience’. Skinner (1971) not only recognised this to be learning, but he regarded his own work as a ‘technology of behaviour’ and so denied the dualism of body and mind. His approach has been described as the ‘psychology of the empty organism’ (Borger and Seaborne 1996: 77), and while there are many reasons to reject this crude behaviouristic approach, its failure to understand the nature of the person-in-the-world is perhaps the most fundamental. Even so, its emphasis on behaviour is still very important, as Macmurray’s assertion that ‘I do, therefore I am’ demonstrates. More recently, learning theory has focused on human experience (see Weil and McGill 1989 inter alia), and there have been many studies from an experientialist perspective. Perhaps the most influential has been that by Kolb (1984), upon which many studies, including my own, have been based. He defines learning as ‘the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience’ (1984: 41). Immediately, we can see that knowledge is still at the centre of his thinking rather than the person. Indeed, in his famous learning cycle (Figure 1.1 is a simplification of his cycle; Kolb 1984: 42) the person is missing.

Figure 1.1 Kolb’s learning cycle.

This simple figure suggests that learning can start from experience or from an abstract idea or theory. However attractive the cycle, it doe...