![]()

1

CULTURE AND PUBLIC RELATIONS

Formulating the Relationship and Its Relevance to the Practice

Krishnamurthy Sriramesh

Introduction and Rationale

Although communication has been innate to humans since the origin of the species, one can reasonably conclude that communication scholarship is a twentieth-century phenomenon. It was in 1914 that perhaps the first national association of communication scholars was formed in the United States as the National Association of Academic Teachers of Public Speaking. Over nearly a century, that association has undergone changes in nomenclature reflecting the widening interests of its members extending beyond speech communication. Today the same association is known by the more generic name of National Communication Association, showcasing a wider array of communication disciplines. Public relations scholarship, whose primary focus is the use of communication to build relationships, has also come of age only since the mid 1970s even though the practice itself can be dated back to pre-biblical times in many parts of the world (Sriramesh, 2004).

Culture, a phenomenon that is innate to human beings, has a relatively longer history of scholarship than communication or public relations. However, attempts to link culture with public relations began only in the 1990s. Although the twenty-first century is not the first time the world has witnessed globalization (see Sriramesh, 2010, for a review of globalization in previous centuries), one might make a reasonable assertion that the onset of globalization in the final decade of the twentieth century and into the new millennium has put culture at the forefront of organizational studies and of communication. Three decades ago, the organizational communication scholar Smircich (1983) noted that “culture is an idea whose time has come.” In 1992, Sriramesh and White (1992) contended that culture’s impact on public relations could not be discounted any longer and had hoped that the 1990s and the twenty-first century would bring increased focus and research on the key relationship between culture and public relations. Even though the Maastricht Treaty and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) had yet to be signed and globalization had not yet become the buzzword it is today, we contended then that “to communicate to [with] their publics in a global marketplace, public relations practitioners will have to sensitize themselves to the cultural heterogeneity of their audiences … The result will be the growth of a culturally richer profession” (p. 611). However, as will be reviewed in this chapter, attempts at studying the key linkage between culture and public relations in the two decades since we wrote that have been few and far between. As a result, the public relations body of knowledge has developed, and continues to develop, ethnocentrically. There is a dire need for studies that will strive to make the body of knowledge more holistic.

A few examples help illustrate the presence of ethnocentricity in practice and scholarship providing the rationale for this book—the first dedicated to assessing the nexus between culture and public relations. First, one sees the wide practice of the adoption, or translation, of American or British public relations textbooks by educators and universities in distant cultures with negligible or no attention given to “localizing” the contents, concepts, and examples (see Sriramesh, 2002, for a longer critique). A second example is the practice in public relations scholarship of discussing values with little or no reference to culture. The Journal of Public Relations Research, a leading public relations scholarly journal, heralded the new millennium with the publication of a special issue on the values (emphasis added) needed for effective public relations practice in the twenty-first century. The thoughtful essays in the special issue discussed, among other things, professional values, activist values, feminist values, and postmodern values, but the term culture appeared only once in the entire issue. Another example is the essay assessing the “state of the field” in one of the premier communication journals (Botan and Taylor, 2004) that did not make a single mention of the relevance of culture to public relations. Further, Botan and Taylor were silent about any developments in the field of global public relations research, which includes the work of at least three or four dozen scholars from Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Europe (and some from the US as well). That is a genre of research that has been developed since 1990 and it is surprising that even the peer reviewers of this prestigious journal did not point out this gap to the authors during the review process.

A similar ethnocentricity can be noted in public relations education as well. As a prelude to the dawn of the new millennium, the Public Relations Society of America (PRSA) tasked the Commission on Public Relations Education (CPRE) in the United States to “determine the knowledge and skills needed by practitioners in a technological, multicultural, and global society [emphasis added] and then recommend learning outcomes.” After due deliberations, the Commission offered its recommendations in its Port of Entry report published in October 1999. These recommendations fell far short of what is required for a robust curriculum that prepares students for operating with the holistic perspective that our globalizing world demands. For example, of the 10 “necessary knowledge” factors that the Commission recommended for PR graduates, only one related to globalism—“multicultural and global issues”—and it was listed tenth. In the list of 20 “necessary skills” that PR graduates ought to possess, only three can be subsumed to contribute to multicultural public relations education: “sensitive interpersonal communication” (13), fluency in a foreign language (14), and applying cross-cultural and cross-gender sensitivity (20) (see Sriramesh, 2002, for a longer critique). The CPRE revised its recommendations in 2006 but the changes vis-à-vis the relevance of culture are minimal and tell us we have a long way to go in making public relations scholarship relevant to a globalizing world.

The above examples also alert us to the fact that “ghettoizing” discussions of “culture” in public relations scholarship, limiting them only to studies related to “international public relations” or “global public relations,” would be a serious disservice both to practitioners and to students. A review of recently published scholarly volumes in public relations reveals the pattern whereby public relations concepts and theories are discussed in almost total isolation from culture, and only as an afterthought one sees brief descriptions of culture, or “global issues” at the end of the volume. A discussion of culture is vital to every public relations concept, strategy, and skill—the central theme of this book. What is culture and how should the public relations body of knowledge view this concept?

Definition and Scope of Culture

The term culture has been variously defined by anthropologists and ethnographers. Kroeber and Kluckhohn (1952) listed over 164 accepted definitions and about 300 more variations of these definitions. The first comprehensive definition can be attributed to Tyler (1871), who saw culture as “that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society” (p. 1). The expansive nature of the term, and thereby its malleability, was also highlighted by Kroeber and Kluckhohn, who defined culture as a “set of attributes and products of human societies, and therewith of mankind, which are extrasomatic and transmissible by mechanisms other than biological heredity” (p. 145). Culture is so all-encompassing that it is hard to define/describe it, and often one is not aware of one’s own cultural traits and idiosyncrasies. This makes culture hard to measure, a key requirement for scholars and researchers. Hofstede (1984) posited that the presence of culture can be seen at three levels: the universal level (at which as human beings we all share certain characteristics), the collective level (at which only those belonging to a certain collectivity share some common characteristics, mainly as a result of acculturation), and the individual level (at which our cultural traits are molded in unique ways by the individual experiences that each of us has).

Acculturation contributes to the sharing of cultural traits. But which factors help determine the culture of a collectivity? Kaplan and Manners (1972) identified four determinants of culture. The first, technoeconomics, is indicative of the impact that technology and economics have on the development of cultural characteristics in a society. At no time in history is this link more evident than in the twenty-first century with the onset of new/social media as a direct result of an increasingly global economy. The second, social structure, refers to the impact of the institutions of a society on the culture of its peoples. As we shall presently see, political and economic institutions, among other things, have a direct impact on culture and also public relations. The third, ideology, is indicative of the values, norms, worldviews, knowledge, philosophies, and so on espoused by the members of a society. Finally, personality refers to the adoption of individual personalities by members of a society based on acculturation that happens at home, at school, and in the workplace. One can see parallels between the collective and individual levels identified by Hofstede and these four cultural determinants.

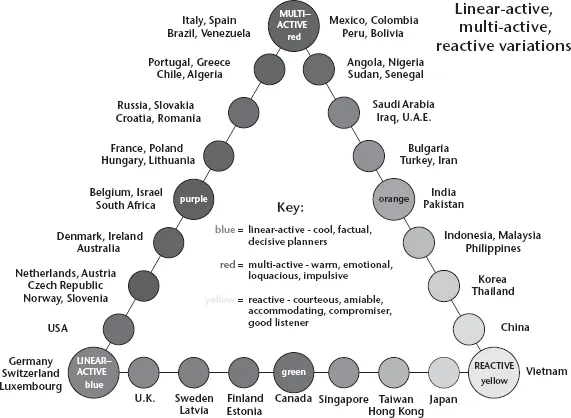

The culture of a society influences, but can often be different from, the culture of organizations in that society, which requires us to assess the relationship between societal culture and organizational culture separately (Sriramesh and White, 1992; Sriramesh et al., 1992). Especially beginning in the early 1980s, there were many studies on organizational culture, which added many new dimensions to the discussion such as the interplay of cultures, subcultures, and countercultures within organizations. Hofstede’s (1984) studies of culture in the organizational context led to the identification of first four and then five dimensions of culture, and his work dominates discussion of culture within organizations. Almost 30 years on from his seminal study in which he sought to assess the cultural idiosyncrasies among managers of an organization hailing from 39 countries, his five dimensions of culture continue to be used by scholars in public relations. After a review of the studies linking culture with public relations (see Sriramesh, 2006), I critiqued the almost sole reliance on Hofstede’s dimensions of culture in public relations scholarship and contended that the field needed studies that would not only look at cultural characteristics that were common across a number of societies (as the dimensions Hofstede identified were) but equally importantly look also at cultural traits unique to a society. Lewis (2006) built on the work of Hofstede and Stuart Hall and offered new perspectives on cross-cultural differences. One such addition is his discussion of what he calls “cultural types.” Rather than pigeonholing cultures as Hofstede did with his cultural dimensions, Lewis offered a continuum on which he placed different countries based on three dimensions: linear-active (cool, factual, decisive planners), multi-active (warm, emotional, loquacious, impulsive), and reactive (courteous, amiable, accommodating, compromisers, good listeners) (Figure 1.1).

Expanding the Scope of “Culture”

In order to link the term culture effectively with public relations, we need to expand the scope of the term beyond societal culture. Because of the interdisciplinary nature of public relations practice, and thereby scholarship, we would have to examine the political culture, economic culture, societal and organizational culture, media culture, and activist culture of a society, as mentioned by Sriramesh and Verčič (2009a). Currently, we have at best a few conceptual linkages between public relations and these five cultures, suggesting that the opportunities for research and knowledge building in this field are plentiful.

In identifying the link between political economy (a combination of political and economic cultures) and public relations, Duhe and Sriramesh (2009) observed that “a political economy approach to public relations examines the interplay between organizations and publics with particular attention paid to the conflicts, expectations, and constraints imparted upon relevant parties by a powerful combination of social, economic, and political forces” (p. 25). We further contended that “the collaborative, democratic, and relationship-building functions of public relations” had the potential to help not only developed economies but also economies that are in the ascendancy, such as the BRIC countries. We (Sriramesh and Duhe, 2009) also offered several avenues for future research linking political economy and public relations under three broad categories: the primary purposes of a nation’s economic activity, the role of the state in the economy, and the structure of the corporate sector and civil society. Several factors are important in determining the relationship between public relation and the political economy of a society, such as the predominant objective that drives a nation’s economy, the roles of liberty, equality, harmony, and community in the economy, the extent to which the economy is open to the outside world, the extent to which the economy is in transition, and the extent to which “winners” and “losers” exist in the economy and the dynamics of the relationship between these groups. One can say with a great deal of confidence that currently the public relations body of knowledge has few studies that have provided empirical evidence linking political economy with public relations—a gap that needs to be addressed in the second decade of the new millennium.

FIGURE 1.1 Cultural Types: The Lewis Model. Source: Lewis (2006) with permission from Richard Lewis Communications (2006).

Although public relations scholars have recognized the innate relationship between mass media and public relations, much of that conceptualization has been one-dimensional, as if there were a single media culture in all regions of the world. Mass communication scholars have studied differences among the mass media in different parts of the world since the mid 1950s, when Siebert, Peterson, and Schramm (1956) offered four normative theories of mass media. Over the next few decades, several other scholars expanded the discussion of the different media cultures in different societies (e.g. Merrill and Lowenstein, 1971, 1979; Merrill, 1974; Hachten, 1981, 1993; Martin and Choudhury, 1983). The normative theories of the mass media offer a useful guide to the differences in media cultures around the world that should be of great use to public relations practitioners. However, with the passage of time and changes in the political (ideological) landscape around the world, these normative theories do not offer the same level of utility as they once did. For our purposes, it would be helpful to reduce the differences inherent in different media systems to three principal factors: media control, media diffusion (outreach), and media access (Sriramesh and Verčič, 2009b). Media control is often confused with media ownership but should be seen as beyond ownership, assessing who has the de facto power to influence media content in a society. This is often a direct manifestation of the political and economic culture of that society. Media diffusion refers to the extent to which the mass media consumed by the members of a society. This can also be explained as the amount of “outreach” of the mass media of a society, which can also be linked to economic culture. Media access is the extent to which the media of a society are open to providing an avenue for the content generated by all members of a society without undue discrimination. A combination of these factors provides us with insights into not only the media culture of a society, but also the other cultures outlined in this section as well. The significant factor to be noted is the i...