![]()

Chapter 1

The Legacy of Health Ineqsualities

Michaela Benzeval and Ken Judge

Introduction

When New Labour came to power in the United Kingdom in 1997 it brought with it a strong commitment to reducing inequality and social exclusion. Its election victory was greeted with great enthusiasm. Many people believed that comprehensive and purposive public action would make a real difference to the growing social injustices that were evident across all aspects of British life. New Labour itself was determined not to waste the opportunity given to it and quickly introduced a wide range of initiatives to tackle social exclusion and poverty. But it became obsessed with detailed issues of delivery. An excessive reliance on top-down targets, and an ill-placed faith in its own ability to micro-manage complex change processes, perhaps reflected the relative inexperience of ministers during New Labour’s first term in office.

Seven years and more on from the landslide election victory that brought the Blair government into power, much of the initial enthusiasm for a centralist approach to ‘big’ government has waned. But the commitment to promoting social justice remains. What has changed is that there appears to be a more sophisticated recognition of the complexity, pervasiveness and durability of the social problems that have to be confronted. At the same time, there is greater awareness of the need to learn the lessons from past attempts to promote social change. With the benefit of hindsight, many of New Labour’s first flurry of social policy initiatives now look naive and over- optimistic. The enthusiasm for evidence-based policy-making, for example, quickly gave way to a desperate scrabble for quick wins to substantiate the ‘can-do’ rhetoric of the government as it became increasingly clear that the scientific basis for effective interventions to reduce long-standing problems such as health inequalities was remarkably weak. In these circumstances, it would be easy to dismiss the first generation of policy initiatives and to move on, but that would be a mistake and a waste. There is much of value to learn from the early attempts by New Labour to deliver on its election promises. This book seeks to contribute to that process.

One strand of New Labour’s initial strategy involved a focus on area- based initiatives (ABIs) to reduce the effects of persistent disadvantage in neighbourhoods blighted by generations of poverty and neglect. Health Action Zones were the first example of this type of intervention, and their focus on community-based initiatives to tackle the wider social determinants of health inequalities excited great interest both nationally and internationally. Like so many other initiatives, HAZs were established in relative haste as high-profile pathfinders that were intended to modernise health care and reduce health inequalities in the most disadvantaged parts of England. One consequence is that they quickly lost their relatively high profile as the policy agenda filled with an ever-expanding list of new initiatives to transform public services and promote social justice. By the beginning of 2003, after most of them had been active for half or less of their intended seven- year lives, they were to all intents and purposes wound up. Nevertheless, the main purposes for which they were established remain important.

So what can be learnt from the experience of Health Action Zones? This book draws on a wealth of findings from the national evaluation of the initiative. It provides a context for and an overview of the HAZ experience, and it explores why many of the great expectations associated with HAZs at their launch failed to materialise. Among the questions it addresses are:

- is there a useful tale to be told about policy failure?

- or is there perhaps a story of progress in the face of adversity?

The answer turns out to be a bit of both. Throughout the book evidence is provided that adds up to the conclusion that HAZs made a good start in difficult circumstances rather than that they failed.

In telling some of the many stories that have to be told to make any sense of the HAZ experience, there are important lessons to be learned about the design, implementation and evaluation of complex community-based initiatives that seek to tackle social problems such as health inequalities. But before our collective impressions of the nature of the HAZ journey and its implications begins, it is important to provide some contextual material about the most important of the issues that they were established to address. To understand both the limitations and the potential of the HAZ initiative, it is essential to have some appreciation of the nature of the problem of health inequalities, the latest scientific evidence about their causes, and the possible role of local action in any strategy to reduce them.

Health Inequalities: The Problem

Health inequalities have been documented in Britain for over 150 years (Benzeval 2002), and despite considerable increases in overall life expectancy during the twentieth century, they continue to persist to the present day (Donaldson 2001). However, what is meant by the term ‘health inequalities’ (Whitehead 1992; Braveman and Gruskin 2003) and how the phenomena are measured (Mackenbach and Kunst 1997; Kawachi et al. 2002) are both the subject of considerable debate. Moreover, there are a number of different dimensions of health inequalities – social, geographic, gender and ethnic – that are considered to be important. There is not room to explore all of the relevant issues here; instead evidence about the main inequalities identified by the Labour government as important policy objectives – geographic and socio-economic (DH 2001b) – is considered. However, most commentators, including the government, recognise that other dimensions of inequalities in health such as those between men and women (Annandale and Hunt 2000) and among different ethnic groups (Nazroo 1999) are important.

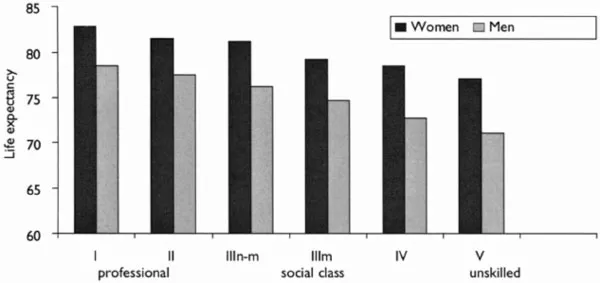

Evidence about inequalities in life expectancy at birth among socioeconomic groups in the late 1990s is shown in Figure 1.1. Taken from the Longitudinal Study (LS), these data show that boys born to professional parents in 1997–9 could expect to live to the age of 78.5, 7.4 years longer than those born to fathers with unskilled occupations. The equivalent gap for girls is 5.7 years.

Figure 1.1 Life expectancy at birth by social class, LS, England and Wales, 1997–9

Source: Donkin et al. (2002, Table I)

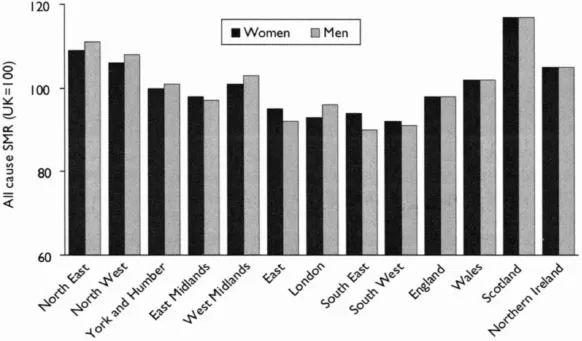

There are also considerable differences in mortality among different areas of the country. Figure 1.2 shows the Standardised Mortality Ratio (SMR) for different regions within England, and the four countries of the United Kingdom. The whole of Scotland and the North East and the North West of England have SMRs considerably higher than the UK average, whereas the South West and the South East benefit from much lower relative mortality rates. As the Chief Medical Officer commented in his annual report for 2001, such differences are ‘not new’:

Figure 1.2 All cause Standardised Mortality Ratios by region, UK, 2000

Source: ONS (2002, Table 3.14)

Throughout the 20th Century, parts of northern England have shown consistently higher mortality than other parts of the country. Despite overall improvements in health, the inequalities gap between socially disadvantaged and affluent sections of the community has widened. A new analysis has shown that some communities in England have death rates equivalent to the national average in the 1950s.

(Donaldson 2001, p. 3)

Donaldson makes two important points that require further exploration. First, he emphasises that such geographic differences are linked to social disadvantage and affluence, and second, that such inequalities are widening.

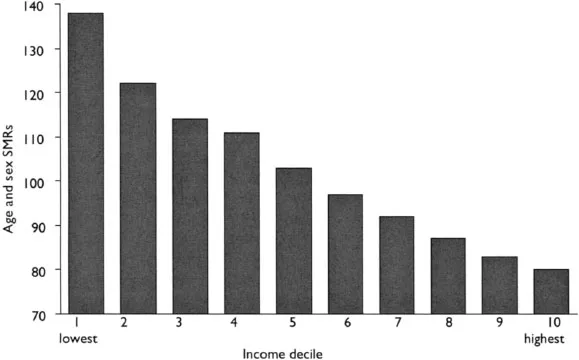

A wide range of studies has grouped geographic areas by different measures of socio-economic status to show that geographic inequalities in health are the result of socio-economic differences among places. For example, Shaw and colleagues (1999) grouped parliamentary constituencies by their average income to show a very steep health gradient. A revised version of their analysis is shown in Figure 1.3. In 1998/99 parliamentary constituencies with average incomes in the bottom 10 per cent of the distribution had a SMR for under-75s approximately 38 per cent higher than the British average, while those areas in the top 10 per cent of the income distribution had a SMR 20 per cent lower than the average.

Figure 1.3 SMRs under 75 by parliamentary constituencies grouped by income, Britain, 1998–9

Source: Davey Smith et al. (2002, Table I)

The same study suggested that inequalities in health among parliamentary constituencies had widened during the 1990s (Davey Smith et al. 2002), while other studies have showed a widening of inequalities between areas in the 1980s (e.g. Phillimore et al. 1994) and within regions in the 1980s and 1990s (e.g. Reid and Harding 2000). Similarly, at the individual level, studies have shown widening inequalities between social classes since the 1970s based on a range of measures of health and socio-economic status (Drever and Whitehead 1997; Hattersley 1999). On the other hand, a few studies have suggested that there may have been a narrowing of inequalities at the end of the 1990s. For example, Whitehead and Drever (1999) found evidence of a reduction in social inequalities in health for infant mortality, and Strong and colleagues (2002) found a narrowing of geographic inequalities in mortality within Trent region. Other studies, however, have found that the way in which inequalities are measured over time can affect whether or not trends appear to be widening or narrowing (Donkin et al. 2002; Rees et al. 2003).

Health status and socio-economic circumstances are difficult concepts to define and measure, and the ways in which this is done can affect the estimate of the size of the problem (Manor et al. 1997; Macintyre et al. 2003). The composition and size of social groups varies over time, and whether or not these factors are considered may affect comparisons over time (Benzeval et al. 1995a). Similarly, whether relative or absolute differences in health are considered, whether differences between two groups (i.e. the most affluent and the most disadvantaged) or across the whole population are compared, and whether simple or sophisticated measurement techniques are employed, will also affect the scale of inequalities estimated from any particular dataset (Mackenbach and Kunst 1997) and hence whether or not they appear to be increasing or decreasing over time.

Despite these measurement difficulties, there is overwhelming evidence about the existence of social inequalities in health across the developed world, with a number of countries beginning to develop strategies to address them (Mackenbach and Bakker 2002). In England, the government has also acknowledged that health inequality is a substantial and persistent problem that needs to be addressed (DH 2003c). The next section, therefore, considers the causes of health inequalities and the general kinds of policy solutions advocated to reduce them.

The Causes of Health Inequalities

A significant landmark event in the study of health inequalities was the publication in 1980 of the Black Report (Townsend and Davidson 1982), an independent inquiry commissioned by the Callaghan government in 1977. The report suggested that the four most likely explanations for social inequalities in health were that they are:

- an artefact of measurement error

- the product of social selection

- caused by individuals’ behaviours

- a result of individuals’ material and social circumstances.

After carefully reviewing all of the evidence available at that time, the inquiry concluded that the materialist explanation was the most significant cause of health inequalities, although each of the others also made a minor contribution.

Since the publication of the Black Report, a huge research endeavour has been conducted to explore and assess the relative importance of these different explanations further (Macintyre 1997a; Graham 2000b). In general, this evidence, which has been based on increasingly sophisticated datasets and analyses, supports the broad findings of the Black Report. However, these explanations are not without their critics and a number of extremely acrimonious debates have developed between academics exploring different kinds of arguments in relation to them (Macintyre 1997a).

Nevertheless, when the second independent inquiry into health inequalities, commissioned by the New Labour government in 1997, reported in 1998 it came to a similar conclusion to that of the Black Report.

The weight of scientific evidence supports a socioeconomic explanation of health inequalities. This traces the roots of ill health to such determinants as income, education and employment as well as to material environment and lifestyle.

(Acheson 1998, p. xi)

Such assessments have been accepted by the government and form the foundation of its strategy to address health inequalities (DH and HM Treasury 2002; DH 2003c), as discussed in Chapter 2. However, such a succinct summary of causation belies the complexity of the underlying relationships and pathways, and hence the difficulties of designing policies to reduce inequalities in health. As Graham (2000b) points out:

A single pathway would, of course, simplify the explanatory task and provide a ‘clear’ steer to policy makers seeking to reduce health inequalities. However, the evidence points to multiple chains of risk, running from the broader social structure through living and working conditions to health related habits like cigarette smoking and exercise. … The chains of risk have been uncovered primarily through surveys of individuals. However, a small seam of research is beginning to locate individuals in the places in which they live and to suggest that both individual factors and area influences have their part to play.

(Graham 2000b, p. 14)

This is not the place to discuss the mass of evidence that explores the different explanations for health inequalities in depth. (For a more in- depth discussion of these issues see the collection of evidence submitted to the Acheson Inquiry (Gordon et al. 1999) or the summary of the findings of the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) research programme on health inequalities (Graham 2000a).) However, the key message is that health inequalities are the result of an individual’s social and economic circumstances across their life course. An important corollary is that a key determinant of health inequalities is the general social and economic inequalities that exist in England at the present time (DH 1998d).

England has experienced considerable social and economic change in the last few decades. A reduction in manufacturing industry and a growth in the service sector has led to a reduction in male employment, particularly among unskilled workers, and a growth in mainly female, often part-time, employment (Graham 2000b). This, together with the increasing number of lone-parent families over the same period, led to a growth in the number of working-age households where no one was in paid employment. By the second half of the 1990s, such families accounted for one-fifth of all working-age households (DH 1999b).

These trends, together with changes in benefit and taxation policies implemented by Conservative governments in the 1980s (Goodman and Webb 1994), contributed to a massive increase in the number of families living on low incomes and consequently a dramatic growth in income inequality, of an almost unprecedented degree compared with other industrial countries (Atkinson et al. 1995). By 1998/99, 14.3 million people (about one-quarter of the population) and 4.4 million children (approximately one in three) lived in households with less than half the average income (Gordon et al. 2000).

Alongside these economic trends there has also been considerable social change. The rise in the number of lone parents has already been mentioned; over 3 million children, one-quarter of all families, live in one-parent households. There has also been a dramatic rise in owner occupation of houses, which has...