This is a test

- 392 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Emerging Concepts in Urban Space Design

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This important work, now available in paperback, from Professor Geoffrey Broadbent, provides a clear analysis of the nature of many of today's design problems, identifying their causes in history and suggesting a basis for co-ordinated solutions. The author discusses `picturesque' and `formal' tendencies in modern architecture, relating them to parallels between philosophic thought and design theory through the ages. Using a wealth of international examples from around the world including America, UK, Italy, Germany and France and with over 250 photographs and illustrations, Emerging Concepts in Space Design offers a fascinating insight into the history and likely future directions of urban design.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Emerging Concepts in Urban Space Design by Professor Geoffrey Broadbent, Geoffrey Broadbent in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

1: Urban space design in history

The roots of planning

If we are to understand the nature of the city it is useful to remember that the word itself derives from the Latin civilis which means ‘befitting a citizen’. We should remember also that the same root underlies our word civilization. Civilization is that which takes place in great cities!

Kenneth Clark (1959) opened his television series on ‘Civilization’ and the associated book by looking at the centre of Paris; at Nôtre Dame, the Louvre, the Institute de France, the town houses and the bookstalls lining the quais of the Seine. Here, he suggested, are all the things which civilization means to us.

As he said, civilization is possible when humankind has reached beyond the level of scratching a bare subsistence and freed from ‘the day-to-day struggle for existence and the night-to-night struggle with fear’, develops in equilibrium qualities of thought and feeling, ideals of perfection in reasoning, in justice, in physical beauty, and so on.

It's a matter of stability too, or as Clark puts, ‘permanence’. The good, solid walls of stone he saw in Paris gave him such permanence, so did the ideas enshrined in the books. Civilization for him was evidence that humankind had extended itself to the utmost, mentally and spiritually.

Some of course will recoil in horror at such elitism. Clark would simply have called them ‘uncivilized’ but they would do well to read what Frederick Engels said in his funeral oration at the grave-side of Karl Marx (1883).

‘Marx’ he said, ‘discovered the law of human history…that mankind first of all must eat, drink, have shelter and clothing, before it can pursue politics, science, art, religion etc’.

The latter Marx called the ‘superstructure’, built onto the economic ‘base’. But once society has passed beyond the primitive struggle for existence economic activity itself, of course, becomes part of the ‘superstructure’. Which puts into context the origin of the city.

The first cities obviously were built when humankind had got beyond the struggle for mere existence. The earliest known city, Jericho (c. 7000 BC) was an oasis near the River Jordan and it has extensive defences whilst Catal Huyuk in Central Anatolia (Asian Turkey c. 6500 BC) seems to have flourished on trade (Mellaart, 1967). Both depended on sophisticated agriculture, including the rearing of livestock.

But city-sized populations in general could not be brought together until ways had been found of producing food nearby, in sufficient quantities and transporting it into the city. So it is hardly surprising that traces of the first great cities on the whole are to be found in great river valleys and basins.

Irrigation on the necessary scale seems to have been developed first of all in central Mesopotamia—between the Tigris and the Euphrates—from about 6000 BC. There the first city-scale developments were built in Sumer, at Uruk (c. 3500 BC), Ur (c. 3100 BC) and Eridu (c. 2750 BC). The first Egyptian cities have been found near the estuary of the Nile, at Faiyum (c. 4440 BC), and Meride (c. 4300 BC). Further south down the Nile beyond Cairo the first two Egyptian capitals were founded, at Memphis (c. 3100 BC) and Thebes (c. 2080 BC). Further east in the Valley of the Indus there were Mohenjo-daro and Harrappan (both before 2400 BC, whilst further east again on the Yellow River, or its tributaries, there were the early Chinese cities such as Erh'li-t'ou (c. 1766 BC) and Cheng-chou (c. 1650 BC).

The presence of great rivers made irrigation possible but as Kenyon says (1960) it had to be organized:

The successful practice of irrigation involves an elaborate control system. A system of main channels feeds subsidiary channels, watering the fields when the necessary sluice gates are closed. Therefore the channels must be planned, the length of time each farmer may take the water by closing the sluice gates must be established, and there must be some sanction to be used against those who contravene the regulations. The implications therefore are that there must be some central communal organization and the beginnings of a code of laws which the organization enforces …the evidence that there was an efficient communal organization is to be seen in the great defensive systems.

Power naturally accrued to those who built and controlled the irrigation systems, not to mention the defences. None of this could have been achieved without centralized planning. Small wonder then, that the first cities show evidence of social stratification and the development of craft specializations.

The little town of Beidha, south of Jericho, had individual shops for specialist workers in bone, workers in stone, butchers and so on, whilst the greatest Neolithic city of them all, Çatal Huyuk had very much more detailed specializations (Mellaart, 1967).

There were specialists in flint and obsidian—a black volcanic glass—who made arrowheads, daggers, spearheads, knives, sickles, scrapers and boring tools, not to mention mirrors of polished obsidian. There were jewellers who made beads for necklaces, armlets, bracelets and anklets. There were workers in stone who made adzes, axes, polishers, grinders, chisels, mace heads and palettes; bone-workers who made awls, punches, knives, scrapers, ladles, spoons, bowls, scoops, spatulas, bodkins and belt-hooks. There were wood carvers who made boxes and bowls, weavers who made woollen cloths and rugs. There were reed weavers, who made baskets and mats; potters, painters, sculptors and other artists. Since some of the houses were a good deal larger than others and since some people were buried much more lavishly than others, there is evidence of social stratification.

So, four things in the first place, made the city possible: the separation of the built-up area from the surrounding countryside, possibly by defensive walls; the development of irrigation systems for intensive agriculture; the development of power structures by which the irrigation systems, and other aspects of urban life, could be controlled—usually by kings and priests; and the development of craft-specialities to serve not only the needs or the desires of the urban population but also as bases for trade.

Since cities were founded in these things, it is hardly surprising that cities ever since have been permeated by them or their equivalents.

As for their physical design, cities and parts of cities, have grown in two ways. The first is described by Alexander (1964) as the natural way in which people simply start building, as they still do in the shanty towns of the emerging world. And then there is the artificial way in which a master plan is prepared; streets laid out, squares and urban blocks on to which buildings are then placed according to some planners’ sense of order (Stanislawski, 1947).

This contrast will recur many times in the book. So will another contrast: between formality and informality. The ‘natural’ city tends towards informality, not to mention an apparent disorder whilst the planners will want their conscious decisions to show. Most planners aim for regularities of a kind which show that human minds have been at work; but some aim for a self-conscious irregularity of the kind we call Picturesque. This book is largely about that contrast but of course it will have to be put into context.

Classical planning

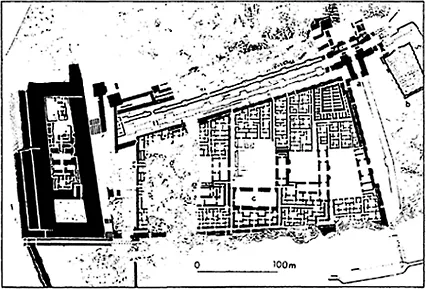

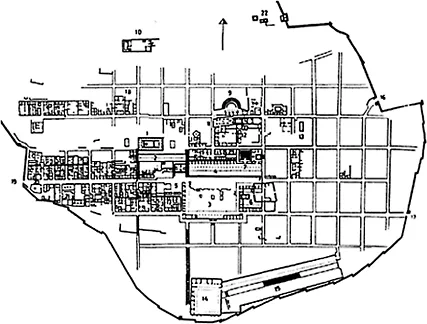

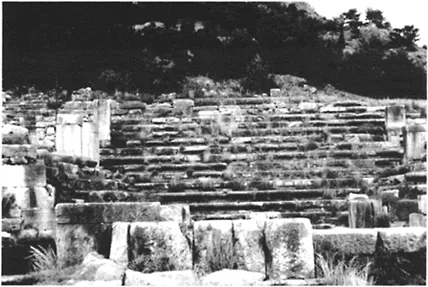

Straight streets, meeting at right angles, were known in Nebuchadnezzar's Babylon which was planned between 1126 and 1105BC (Fig. 1.1). Aristotle in Politics (ii, 5) seems to have thought such planning was invented by Hippodamus of Miletus (479 BC) who, he says: ‘discovered the method of dividing cities’. Miletus was planned on a checkerboard or grid as many later cities have been. But so was its neighbour, Priene, built on steeply sloping ground with the main streets running along the contours and the (stepped) minor streets crossing them (Figs 1.2 and 1.3). Indeed, as Kostoff says (1985), the preferred Greek method of planning was per strigas, that is to say by bands in which east-west avenues were crossed, at right angles, by one or more north-south streets.

Such ancient texts as survive on city planning are concerned, not so much with the geometry of the streets, as with aspect, prospect and climate. Hippocrates, for instance, suggests (in Airs, Waters and Placesiii–iv) that the healthiest aspect will be facing east and Aristotle agrees (Politics vii, 10.1). If it cannot face east then the city should face south. Vitruvius too is concerned with prevailing wind (I, 6. i): broad streets will be open to the winds but the smaller alleys should be protected. ‘Cold winds are very unpleasant; hot winds ennervating, humid winds unhealthy’

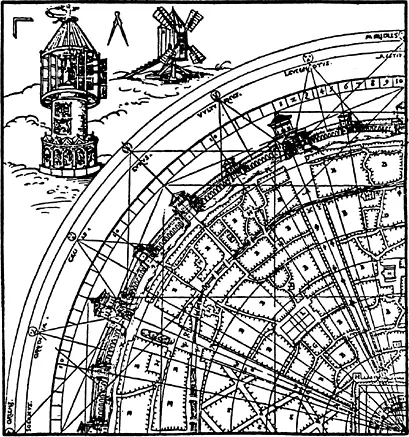

Vitruvius, indeed, has much to say about the winds and other environmental matters in choosing the location for a city (Fig. 1.4). The first need, he says, is for water. So (VIII, 1. i) one ought, before sunrise, to fall flat on one's face, supporting one's chin on the ground so ‘the sight will not wander higher than it ought’. Thus one can observe where moisture ‘seems to curl upwards and rise into the air’ after which digging will confirm that indeed there is water to be found.

Fig. 1.1 Babylon: Nebuchadnezzar's South Palace (c. 1126–1105 BC) (from Oates, 1979, p. 100).

Fig. 1.2 Priene (c. 350 BC): Gridiron plan (from Akurgal, 1978).

One should observe what kinds of plants seem to flourish on site for these will be good climatic indicators, the flavours of the fruits, not to mention any wine. Above all one should look at the cattle for, as Vitruvius says (I, IV, 9) If the livers were not, they moved to a different site.

Fig. 1.3 Priene (c. 350 BC): the steeply terraced streets (author's photograph).

Rykwert (1976) goes into considerable detail about the ceremonies by which Roman cities were founded and there is no need here to repeat his splendid account.

As for winds, Vitruvius thought there were eight—as represented on the Tower of the Winds in Athens. The Tower is octagonal, facing the eight winds and so, accordingly, should a city be planned.

Since its sides would face the eight winds, Vitruvius says (V, 7) ‘let the directions of your streets and alleys be laid down on the lines of division between the quarters of two winds’ so no wind would blow directly down them. For if the winds blew directly into the street they would blow even more strongly as they were confined. They would be dispersed, however, if they blew towards the angles of the buildings.

Vitruvius is so proud of this account that he repeats it then goes on to prescribe locations for the major temples, the forum, the basilicas ‘which should be in the warmest possible quarter’ and so on.

He assumed that the city would be walled, with defensive towers projecting from the walls. Access roads should slope upwards towards the city gates which should be approached from the right so that enemies, carrying their shields in their left hands, would expose their unprotected flanks to the defenders.

Vitruvius suggests (I, V, 2) that towns should be laid out: ‘not as an exact square, nor with salient angles, but in circular form, to give views of the enemy from many points’. He is clear that any ‘salient angles’ made defence more difficult because, instead of protecting the defenders, they protected the approaching enemy.

Fig. 1.4 Vitruvius: Diagram of the Winds from Rivius, G.H. (1548) (Vitruvius Teutsch, in Rosenau, 1959).

Our ancestors, when about to build a town or an army post, sacrificed some of the cattle that were wont to feed on the site… and examined their livers. If the livers…were dark coloured or abnormal, they sacrificed others to see whether the fault was due to disease or food. They never began to build…until…they had made many such trials and satisfied themselves that good water and food had made the liver sound and firm.

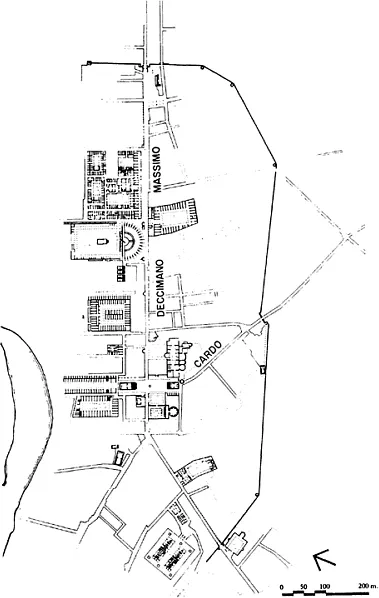

Fig. 1.5 Ostia: cardo maximus and decumani (from McDonald, 1986).

Despite Vitruvius's predilection for circular cities, most Roman planning followed the Greek gridiron form.

One Roman surveyor, probably Frontinus, describes the method for setting out a town (quoted Pennick (1979)): once the centre had been located, the augur identified it as the omphalos—from which the city, not to mention his survey, originated.

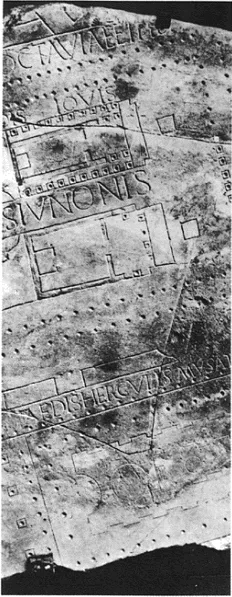

Fig. 1.6 Part of the ‘Forma Urbis’, the marble Map of Rome set up for Septimus Severus (3rd century AD) (from Bacon, 1967).

He sat at this point facing west and of course the four major directions could be laid out. In setting out the city, one should start with an amussium—an absolutely level marble slab—on which one should set a bronze gnomon, a ‘shadow tracker’. By tracing the shadows at certain specified times one could plot a line running due north to south and use this as the basis for setting out one's city.

Agrimensores laid out the lines of two major roads, the decumanus maximus running from north to south and the cardo maximus running from east to west (Fig. 1.5). Along these roads both town and country were laid out in squares although as Dilke (1971) says, the country was ‘squared’ in centuriae of 2400 Roman feet each containing 200 ‘heritable plots’ whilst the town was laid out in urban blocks, insulae which varied considerably in size although acti squares—a little less than half a mi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgements

- Part One: Historical Perspectives

- Part Two: Philosophies and Theories

- Part Three: Theories into Practice

- Part Four: Applications

- References