eBook - ePub

Adapting Buildings for Changing Uses

Guidelines for Change of Use Refurbishment

This is a test

- 136 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book provides practical guidance on the refurbishment of buildings, enabling them to be used for different purposes from those for which they were originally designed Based on a research project at the Bartlett School of Graduate studies, University College London, UK The book is written in a highly accessible style with bullet-point checklists and lots of illustrations The author considers all the different aspects of adapting a building, such as cost, value and risk, explain the importance of all the parties involved in such a project and look at how to avoid common problems

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Adapting Buildings for Changing Uses by David Kincaid in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Adaptive reuse

1.1 Introduction

In considering the potential for buildings to be adapted to different uses it is helpful to start by looking at the question from the simple two-dimensional standpoint of the floor area required for different specific activities. This ignores height, strength and many other ultimately important physical characteristics that are necessary to detailed design, but by focusing on activity, not ‘use category’, allows us a clearer view on the commonalities of human activities whatever the use setting. This two-dimensional space view was explored in research done in the 1960s which looked at the problems created by rapid growth and change in buildings designed for hospital and school use. Peter Cowan, then at UCL, investigated this question and reported his findings to the Bartlett Society2 for a large and varied number of different activities (Cowan, 1963). He showed that when all sizes of spaces used for a generic set of human activities were plotted against frequency of occurrence, the peak of the curve of space provision occurred at only 20 square metres and fell away sharply thereafter as space size increased. Also, spaces as small as 2.5 square metres were found to be appropriate for a wide range of useful and necessary activities. These findings indicated that the potential for buildings which may appear constrained by internal configurations, shape or structure (as well as for those that are large and relatively unconstrained physically) to be adapted for a wide variety of uses is not especially limited by the space needs of a significant range of human activities.

This suggests that most buildings are physically suitable for adaptation to most uses, and influenced the proposition that ‘long life – loose fit’, which was popular in the 1960s, should be a guiding principle behind most design briefs. This longer view of use potential has recently seen a revival under the sustainability agenda as reported at the 2001 AIA convention.3 (Plugman, 2001). The research supporting this book also confirms this idea of the general utility of buildings. However, while this encourages adaptation as a serious alternative to demolition and new build, it does not help to determine which new use is best suited to a particular building in a particular location at a particular time. This more complex issue, which has much greater relevance to the problems of today’s cities, and is a primary concern of anyone considering the fate of a particular building, is a major part of the material covered by this book.

To investigate the issues relating to which new uses are likely to be functionally and financially viable for an existing building required that as researchers we explore the complexities of existing practice in adaptive reuse. To do this it was necessary to identify and categorise all of the major players involved in making the decisions and implementing adaptive refurbishment projects at present, from financiers to users. It also involved establishing a rigorous framework of criteria for decisions, such as those relating to risk or cost, from which the enquiries could be developed. Some of the detail of these investigative mechanisms is described in the following sections in order to provide the reader with what it is hoped will be a convincing explanation of the results and how they may be used to provide guidance on which use may be most appropriate for a given building. Additionally, this is intended to allow the reader to make better use of the guidance given on project delivery, funding and marketing.

It should, however, be pointed out that the book does not deal with the well-known and established techniques and knowledge bases associated with design, project management, costing and project financial analysis. The literature on these is extensive and of long standing, as are the programmes of study in all these areas. All of these are considered by the author to be as valid and well tested for refurbishment projects as they are for new projects, and as such were not part of the research.

What is provided here is a fresh understanding of how an extensive range of physical and locational characteristics can be considered in a systematic way to provide guidance on what uses are best suited to an existing redundant building and how those aspects of funding, design and project management which are unique to adaptive reuse can be more effectively handled to improve the chances of success in this field. The uses which emerge are much more specific than those normally referred to in planning regulations and are much greater in number. The management issues identified alongside the issues of use choice focus on the problems that arise due to the differing perceptions and interests of those involved in this work. The benefits of assembling project teams from those experienced in refurbishment are also described and discussed.

The book begins by dealing with the topic in the context of the UK; however, a number of references are made to US and Canadian practice which show many consistencies with the UK and the research results developed here.

1.2 Refurbishment practice in the United Kingdom

Scale of the refurbishment market

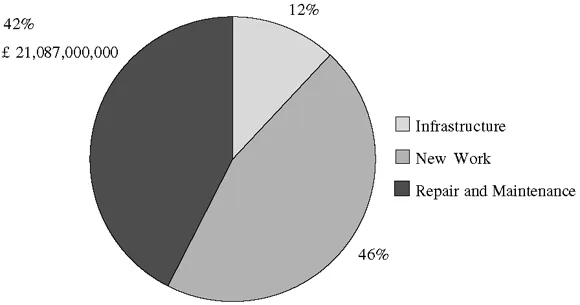

The scale of the refurbishment market in the UK has been growing steadily since the 1970s. By the mid-1990s refurbishment activity represented 42% of the total construction output (categorised by Government as repair and maintenance), worth in 1995 £21,087,000,000 (National Statistics, HM Government, London) ( Figure 1.1 ).4 This represents a two-fold increase in this sector since the 1970s, when it represented 22.5% of the total construction output within the UK. The two main categories of this work are housing (56%) and commercial (44%). Within these figures lie most of the refurbishment activity that involves change of use. Government planning application statistics put this at 9% of all building activity, but this may be an underestimate because often large-scale refurbishments must be designated as new building activity, as are all cases where housing is converted to other uses. Thus it is likely that change of use refurbishment is an activity involving expenditure of at least £5 billion annually in the United Kingdom.

Each year some 1.5% of the building stock of the UK is demolished,5 (Department of the Environment, 1987), mainly to be replaced by new buildings. A further 2.5% is subject to major refurbishment and renovation. Therefore, in any one year no more than about 4% of the national building stock will be in the process of physical change, the rest being subject only to routine maintenance and minor modification. As a consequence, there is a considerable inertia in the available stock of buildings, with a minimum 2–5 year time lag in the adjustments to the supply of new and adapted property to meet changing demands. Changes in the quantity and quality of demand for buildings over the 5–10 year medium term mainly have to be accommodated by the existing stock rather than by new-build developments. Unless building life expectancies reduce dramatically, and replacement rates increase accordingly, the changing requirements of building users must continue to be met by moving to more suitable premises, or through the adaptation and better management of the existing stock.

Figure 1.1 1995 construction output by type of work as a percentage of total output of £49,826 million.

Source: Department of Environment 1995 Construction Output Statistics.

Change of use characteristics

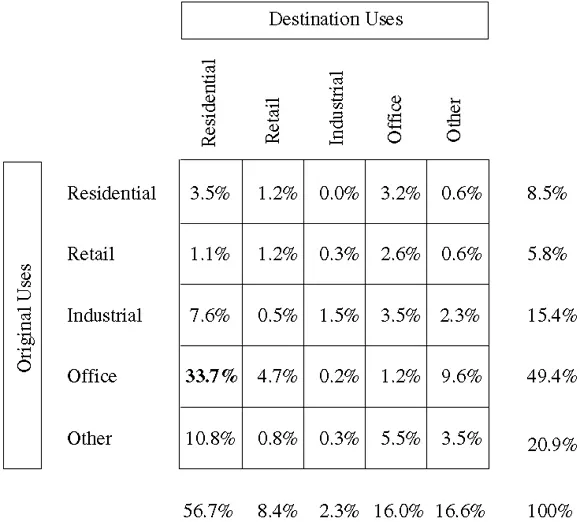

A sample of planning applications from the London boroughs most active in change of use activity from January 1993 to November 1994 (Barnet, Croydon, Camden, Hackney, Islington, Tower Hamlets and Westminster) shows the broad direction for these ‘change of use’ proposals. Figure 1.2 shows an origin–destination chart with the planning figures incorporated under the relevant use class. These are typically broken down into five broad categories: Retail, Office, Industrial and Warehouse, Residential, and Other (Institutional and Leisure). Changes out of office use accounted for 49.4% of all origins, and changes to residential accounted for 56.7% of all destinations. Four types of ‘change of use’ were dominant: Office to Residential (33.7% of all cases), ‘Other’ (public buildings, education, hospital) to Residential (10.8%), Office to ‘Other’ (9.6%), and Industrial to Residential (7.6%), all as shown in Figure 1.2 .

Figure 1.2 Origin and destination uses of planning applications involving ‘change of use’.

Source: APR database for January 1993–November 1994 for the London boroughs of Barnet, Croydon, Camden, Hackney, Islington, Tower Hamlets and Westminster (n = 344).

This origin–destination approach to ‘change of use’ analysis, making use of existing statistical data, could provide a valuable but simple management tool for planning authorities in the future. However, for planners as much as for developers, at present ‘change of use’ refurbishments are tackled in an ad hoc manner. Options are considered on a ‘project by project’ basis with experience remaining private to the individual firms involved. In these circumstances, the development of ‘best practice’ procedures is limited, with few opportunities to establish guidance for the avoidance of project failures. The knowledge base to inform refurbishment decisions has been developing rapidly but remains inadequate in the context of ‘change of use’ refurbishment, where there is a critical gap in research understanding and application. Literature surveys show that while there is planning guidance concerning change of use6 (Department of the Environment, 1991) and the reuse of redundant stock7 (URBED, 1987), this does not address technical problems and issues. There are no operational methods for the identification of the strategic options for refurbishment to new uses; neither are there established techniques for testing and comparing the relative value of options. As a result, the ability of property owners, user organisations and the property professions to assess the risks and benefits of alternative refurbishment measures remains limited.

Legal framework

However, the current approach is influenced less by management approaches such as referred to above and rather more by legal frameworks. Law regulates the use that is made of buildings. So the history of the adaptation of buildings is, to some extent, a function of these legal regulations, the ways in which they have been interpreted in the past, and the ways in which they are being applied today. Legal controls are slow to respond to changing circumstances. Planning and building regulations tend to operate in a form that, while suited to the circumstances of the past, is often inappropriate to meet contemporary conditions. The regulatory framework may therefore retard the dynamics of change and actually contribute to the problems that it was established to control.

Historically, the laws that control building use have rested on an assumption that the classes of land use and building use types are relatively permanent features, around which an appropriate and beneficial regulatory system for the built environment can be achieved. The regulations of use have been directed negatively, to avoid developments having detrimental effects on public health, welfare, amenity, and existing employment; and positively to control development, to promote economic activity and the creation of jobs, to conduct public consultation regarding proposed developments, to help achieve safety at work, to conserve heritage buildings, and recently to encourage mixed developments where appropriate.

The practical legislative position in the UK is complex, with more than 150 statutory measures for regulating the built environment. However, four major areas of legislation are particularly relevant to the adaptation of buildings. These are:

- • Town and Country Planning Act 1990

- Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990

- Building Act 1984 and Fire Precautions Act 1971

- ealth and Safety at Work Act 1974 and Environmental Protection Act 1990.

Each of these Acts has a set of ‘Regulations’ and ‘Orders’ which focus on specific areas of concern, targeting particular issues for implementation.

From a legal viewpoint, adaptations for change of use are of two basic types. First, there are changes from one use class to another, for example from commercial to residential use. Second, there are changes of use within the same use class, for example the division of a commercial development into a number of permanently separate office units.

From a legal viewpoint, adaptations for change of use are of two basic types. First, there are changes from one use class to another, for example from commercial to residential use. Second, there are changes of use within the same use class, for example the division of a commercial development into a number of permanently separate office units.

Evidently some legislation, particularly those parts that now recognise mixed development and multiple use, has moved towards an understanding of the importance of adaptive reuse. However, this book is not concerned to outline the systems of constraints that apply to this field, but rather to look at how better to effect the changes and understand the opportunities.

Accordingly, the next section will attempt to explain some of the basic supply and demand factors working on adapting buildings to new uses.

Accordingly, the next section will attempt to explain some of the basic supply and demand factors working on adapting buildings to new uses.

1.3 Changing use demands and existing supplies

Today the nature and pace of change within organisations and for individuals is having significant impacts on the built environment. Driven by information technology, global competition and environmental concerns, new organisational structures, flexible employment arrangements, novel working practices and changing demands for transport facilities are rapidly emerging. These fundamental developments are resulting in profound adjustments to the demand for, and the use of, urban space. Demand side changes of this kind in the UK, alongside recession, resulted in unprece- dented high levels of under-utilisation, lon...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures and tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1: Adaptive reuse

- Chapter 2: Finding viable uses for redundant buildings

- Chapter 3: Securing the management of implementation

- Chapter 4: Robust buildings for changing uses

- Appendix: Use Class Framework

- References