Chapter 1

The dramatic contexts

To recapitulate the Introduction, the word ‘context’ needs to be treated with care, as the word is used, and used frequently, with two entirely distinct connotations throughout the book: ‘real’ and ‘fictional’. ‘Purpose’ and ‘role’, therefore, are two words which have two entirely different connotations according to which ‘context’ is being invoked. Furthermore, in any dramatic event, within the real context there is always at least one further contextual layer, and sometimes two, the context of the medium and the context of the setting.

THE REAL CONTEXT

The background to any drama experience is the percipients’ own real context. This is taken to mean the real pattern of relationships and situations from which the whole text which is the dramatic event arises—all the people involved in making the dramatic event (with the functions of writers, teachers, actors, directors, interpreters, audience, participants, etc.) and the social, ideological and cultural context in which they are living.

THE CONTEXT OF THE MEDIUM

The coming together of people for the event itself creates an intermediary context of the medium. A somewhat equivocal truth about drama is that it is always ‘an event of special significance…it generates meaning’.1 It is a group art, whose action and meanings are collective. There has to be a coming together of people, who separately or simultaneously embody a number of distinct functions. This takes place in what is, or must become, a specialised location, where the art form is expressed and communicated through the medium of some of the percipients, augmented by performance elements.

In conventional genres of western theatre, this coming together happens in a theatre, which is basically a building or space which is designed to make it easy for the participants to create the fictional context, and for the audience to believe in it. That is why auditoria are usually darkened, with as few extraneous activities as possible going on, to keep the audience focussed on the fictional action and help them forget those elements of the real which are incongruent with it. The theatre is not just an external setting for the drama, like a randomly chosen picture frame, but germane to the social occasion that is a drama, which many of the participants are engaged in creating for the audience, who are not there by accident, but by contract. The makers of the drama, and where and when it happens, are therefore all part of the medium by which the elements of dramatic form are made manifest. I call this contextual layer the context of the medium. Some scholars prefer to use the term ‘the performance context’, but when dealing with processual genres where there may be little performance as such, like drama in education and TIE, this can be misleading. Even if there is no theatre building, if the drama takes place in a classroom, this context of the medium is present: there has to be an agreement to use the (often unyielding) space for the fiction; the group has to be united in agreeing to have a drama. This is one reason why some teachers are scared of using drama with their classes: you can’t impose an agreement to do drama, it has to be negotiated with the children. If one child refuses to accept the group’s fiction —who, when the rest of the class are tensely engaged in rescuing the orphans’ gold from the dragon’s cave, loudly states ‘There isn’t a dragon, it’s just Philip’, or in egotistical bravado creates his own fiction and zaps the dragon, cave and orphans with a raygun—the dramatic context disappears, and with it the drama. Both of those responses happened to me within the same drama, and I assure you it is so. In a theatre, this contract for drama is made easy: the people are there voluntarily, drama is what they expect will take place, and those who are audience accept that their path through the fictional context has been preset by those called playwright, director and actors, and that they have prescribed ways both to respond and not to respond.

Inexperienced audience members may be confused within this context of the medium and shatter it by incorporating inappropriate responses into the fictional context from their own real context—such as the legendary American cowboy at a nineteenth-century touring melodrama, who rescued the (fictional) heroine by shooting (really) dead the actor playing the villain. Less spectacularly, this phenomenon often happens in children’s theatre, and even cinema, where children unused to theatre gratuitously supply their comments on and assistance to the action. This happens so frequently that encouraging loud but limited and peripheral audience participation long ago became incorporated into the context of the medium as a convention of children’s theatre and Saturday matinée cinema: ‘Hellooooo, Uncle Arthur!’ and ‘Look out behind you!’

THE CONTEXT OF THE SETTING

Sometimes, drama happens in places which are not specifically designed for drama, and where the participants may have different purposes from doing or watching a drama, places such as a shopping mall, or a pub…or a school. This may be said to form another layer of the whole context, the context of the setting, where the setting imposes very dominant messages which make drama difficult, and so the renegotiations have to be either very beguiling, in order to deflect the hoped-for percipients from their other purposes (like shopping), or very specific, in order to persuade them that the drama’s purposes are in fact in line with their own. For instance, in Brisbane where I live, during the International Expo 1988 street theatre on site was one of the most popular attractions. For audience and performers alike it was far easier and more successful than in a normal shopping centre on a Saturday morning, since entertainment and spectating formed part of the purposes of the pedestrians at Expo.

Drama in education and theatre in education are two more such genres. They take place in settings which actively mediate against the ready suspension of disbelief; schools have very specialised purposes, and very strong messages of reinforcement for them— many of the practices of schooling are specifically designed as focussing devices for those purposes. In such cases, steps must be taken to ensure the transformation of the context of the setting into one congenial to the medium or art form.

In fact, an inadequate awareness of the potency of the context of the setting has been one of the major factors hindering the growth, effectiveness and recognition of drama in education in schools. For a class to take drama seriously it is necessary for the teacher to persuade the clients—and colleagues, usually—that drama will contribute to their learning; that is the students’ expectation of what a school day is for. This is why drama teachers do not like drama being regarded (as it often is) as a reward subject, or one to fill up a wet end of term Friday; this automatically devalues the experience in the eyes of its participants because it has nothing to do with their real purposes.

THE FICTIONAL CONTEXT

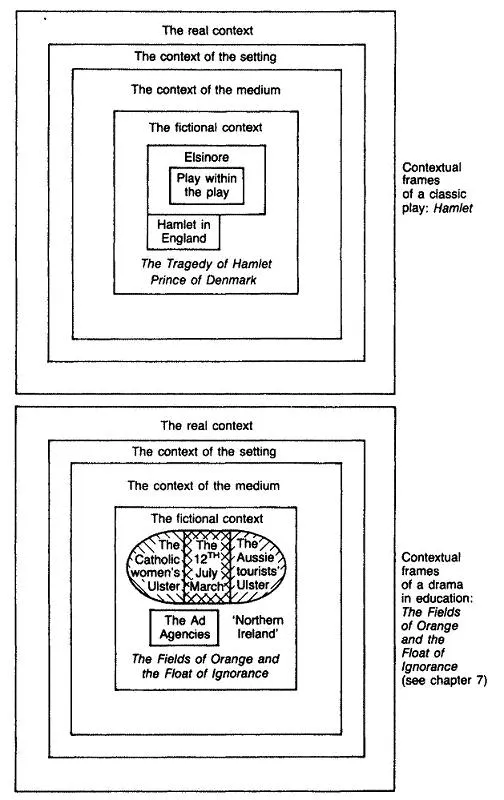

Within these layers of the real world, a fictional context is created, consisting of a situation and characters—the selected and focussed pattern of fictional or fictionalised human beings, their location and their relationships which are the subject matter of the dramatic narrative. Figure 2 indicates a few of the internal frames which may exist within the fiction. In terms of the elements of dramatic form, only the fictional context is an element of the drama itself, the primary one in terms of where this book starts.

CONTEXTUAL FRAMES

In other words, the whole context incorporates numerous contextual layers or concentric frames, three of which are external to the drama itself, which forms the fourth, and which may itself contain several more. It is little wonder that conventional literary theory has tended to find drama too hard to analyse in linear terms. This may be depicted as shown in Figure 2, equally for a conventional play (Hamlet) and for a drama in education (The Fields of Orange and the Float of Ignorance, described in detail in chapter 7).

In one very important sense, fictional context is a derivative from real context. It is a particular framing of aspects of the real, for purposes which relate very directly to the real, and the real network is never fully or deeply suspended. This is particularly true in the genre of drama in education. In a genre like this, where the audience are also simultaneously pro-active participants, it is very hard totally to separate the messages and meanings belonging to the real context, the setting and the medium from those of the dramatic fiction. The real context and the context of the setting are virtually unchangeable within or by a drama, though that cowboy in the melodrama audience certainly crudely altered one actor’s reality. Short of such drastic action, the real context cannot be renegotiated within the active life of a drama, though the whole polemical theatre movement, and drama in education, are predicated on the belief that some change in the real context, however minute, is possible as a result of the drama. However, the context of the medium is more negotiable—as we have seen, a theatre can be replaced by a shopping mall, a schoolroom or even a tramcar—though not without effort. The fictional context, the subject matter of the drama, is entirely negotiable. All four layers are interdependent.

Figure 2 Contextual frames in drama

In drama there must always be some congruence between the real context and the fictional context, and the ideological purposes within that context, whether subversive or reinforcing of the contextual values and attitudes, cannot be achieved without the control and management of this congruence.

DRAMA IN EDUCATION: CHOOSING A CONTEXT

The notion of allowing the clients to select their subject matter has been a vital factor in the development of drama in education from the time of the pioneer practitioner Peter Slade (the 1950s). This, according to Slade, was a concomitant of harnessing the natural instinct towards dramatic play inherent in children. Slade and his followers respected (to a point of encouraging random ideas, sometimes) the offerings of children, trusting them to reach ‘significance’, which for him lay in the natural patterns of the art form, and in particular the patterns of archetypal symbolic movement, which emerged automatically from children’s play.

Whilst young, the Person has ideas already. The ideas are shown to us by words and action…where the right conditions prevail we begin to see the now unmistakable signs of an intended [Slade’s italics] art form…it is the dawn of a certain seriousness… Their language contains moral and philosophic references, a new poetic flow and views which often surprise. The period is one of…great enchantment, and the extra sensitivity that is developed brings the Child to the threshold of the most wonderful years of Dramatic fulfilment.2

Though many later practitioners would not subscribe to the unrestrained romanticism of the thought and the language, Slade’s willingness to negotiate the subject matter of the drama with the clients has led to one of the most characteristic conventions of drama in education: ‘What shall we make a play about?’ This convention seeks to assist the participants to arrive as a group at a central focus which can be both sustained and modified by further questions as the drama proceeds, eventually creating a fluid but clear contract which holds the action together. This is dealt with in detail later in this chapter and in chapters 6 and 8.

While the language and romanticism of Slade are clearly Rousseauan (though Slade does not explicitly acknowledge Rousseau), the ‘deep soul experiences…and ice cold logic’ to which he is referring are derived from Jung (whom he does acknowledge3). For Jung, the collective unconscious may be revealed through forms of action, such as religious ritual, which are in fact dramatisation: ‘organised religious ritual expresses… the living process of the unconscious, in the form of the drama of repentance, sacrifice, redemption’.4 These revelations through symbol, myth and ritual will ‘naturally’ evolve in any community given time.

Time is usually the problem. The succeeding generations of drama teachers found that these natural processes, if indeed they exist in the lyrical forms of Jungian psychology invoked by Slade, are usually severely inhibited by the contexts of setting in which they happen. Schooling is neither automatically educational liberation nor cultural enrichment, as three drama educators from different genres, Bertolt Brecht, Albert Hunt and Brendan Butler,5 combine to make eloquently clear. Books much read by drama teachers have included How Children Fail, Deschooling Society, Teaching as a Subversive Activity, School is Dead and Pedagogy of the Oppressed.6 At the very least, the drama teachers have discovered that ‘Schooling is but a small part of education…,’7 and the negotiability of the art form in pragmatic terms as well as philosophical/ideological ones is bounded by the messages of that schooling which forms the intermediate context of setting.

A theatre is a physical environment designed to assist the creation of drama, by neutralising the messages of the real context—in a standard theatre, by the concentration of focus upon a specially recreated location, while the rest of the space is temporarily suspended in silence and darkness. A schoolroom, which is where the vast majority of drama in education and TIE events take place, is entirely different. The expectations of the participants are that non-fictional events are what normally take place, that the ‘learning’ which goes on in a classroom is part of the ‘real world’. Objectivity holds sway. The physical environment obtrusively reinforces this: the physical setting of the furniture, the concomitant sounds of bells, the properties like blackboards and pens, reinforce the normal activities, which are the outcomes of the status relationships and purposes of the participants—namely, that the room is where this ‘learning’ happens, through the medium of a teacher teaching children ‘subjects’. Therefore, far from being an easy or appropriate environment for Slade’s ‘natural forms’, the classroom discourages the kind of ‘absorption’ which is for him a prerequisite for the automatic elevation of children’s ideas into significance. In other words, the dynamics of drama are actively at odds with the environment. This is dealt with in detail in chapters 5 and 6. There are two ways in which drama teachers have coped with this incongruence, and these two approaches have formed the foundations of the two major strands in drama in education (and the base of one of the two major dichotomies that have bedevilled the movement):8 (a) drama as ‘service’; (b) drama as ‘subject’.

DRAMA AS SERVICE

Teachers have attempted to play down this conflict between the environment and the art form, by seeking congruence, firstly of expectation, then of subject matter. This movement has often typified itself as ‘drama as a service’ within the curriculum. School is where certain subjects are ‘normally’ taught, so drama makes it its business to fit in with those subjects, to be a teaching method. The fictional contexts are taken directly or indirectly from these subjects, and the allied explic...