eBook - ePub

Eating Disorders and Magical Control of the Body

Treatment Through Art Therapy

This is a test

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

People with eating disorders often make desparate attempts to exert magical control over their bodies in response to the threats they experienced in relationships. Mary Levens takes the reader into the realm of magical thinking and its effect on ideas about eating and the body through a sensitive exploration of the images patients create in art therapy, in which themes of cannibalism constantly recur. Drawing on anthropology, religion and literature as well as psychoanalysis, she discusses the significance of these images and their implications for treatment of patients with eating disorders.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Eating Disorders and Magical Control of the Body by Mary Levens in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Psychotherapy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction to magic

Magic is a vast subject in its own right. I shall be selecting from this field only those concepts which have influenced our past and present modes of thinking and behaving and which have affected the ideas of both society as a whole (our culture) and individuals. I will not be examining the social and political implications of magic.

How does magic enter into the field of eating disorders? The linking concept is that of ‘magical thinking’. However, it is important to distinguish between magical ideas as they exist within various cultures and the type of magical thinking on which I shall be concentrating as part of the pathological defences of patients with eating disorders.

My understanding of this distinction lies in the function of magic. Evans-Pritchard, a British anthropologist of the 1930s, considered magic to be an important institution in some societies. The magical belief systems operate to enhance the overall functioning of the group or society and they can actually serve to reinforce essential functions such as social and economic processes within these societies. The function or role of magic therefore depends upon the structure of the society in which it is maintained. This ‘social magic’ stands in direct contrast to the magical thinking employed by patients with eating disorders, which serves no such social function. Their magic results from desperation. Their magic is one which they feel is the only effective means of surviving, and is aimed at retaining a sense of self which may often imply a magical disconnection from their own bodies. Rather than helping them to become more integrated into their social group, their magic results in their becoming more and more isolated from their own families and social network.

Thus, the magical ideas employed by patients with eating disorders serve no useful social function. However, because these patients feel that these ideas are all that they have left, the magical thinking acts as a means by which, isolated from their own social group, they can strive to maintain some sense of self and thereby defer or prevent the acceptance of their own bodies. The patient with an eating disorder feels that reduced body mass and content equates with reduced experience of having a body and feelings. Examples of this magical thinking can be seen in her artwork, where she believes that images of secure boundaries around self-portraits will effect greater security. With relation to food, obsessional defences against contact with calories enables her to believe that this will protect her from an everpossible invasion by (life-embodied) foodstuffs. The magic to which the patient with a severe eating disorder resorts is indeed a means of attempting at all costs to avoid the slow, arduous process of growth. For some it involves a painful wrench away from the primitive and familiar way of existing.

If we were suddenly to find the ability to control the world by the wave of a magic wand—to find that all of our needs could be instantly met without the need to wait in anxious anticipation; that our most desired wishes might be granted; that we were protected from the loved person who might suddenly turn on us, thereby wiping out all that we had once relied upon—then surely we would, with the greatest reluctance, hand over our wand in exchange for an assurance that a healthier person has no need to control his/her environment in such a way; that the potential benefits of living in the real world (which of course demands that we tolerate frustration, disappointment and pain) truly do outweigh magical control.

If we have been lucky enough to discover the benefits of a healthy adaptation to reality, so that there is no need to construct an alternative world to live in which is defined by our own rules of reality, then it may seem to us illogical to imagine opting for the ‘quick fix’. After all, we accept that living a life dominated by instant gratification, by finding ways to reduce discomfort immediately, leads to a withering of our mental muscles. It leads, in other words, to a lack of development of our capacity ever to bear the anxieties of life (our responses to external difficulties), with the result that we will be constantly on the run from them, whether through abusing a substance or withdrawing from the external world. Watching videos or compulsively playing computer games may contain some of the same elements of escape from reality that is achieved by heroin or alcohol abuse. As yet it is not so apparent how the abuse of food or of the body serves the same function. Links can be made between the various ways in which human beings attempt to construct their own reality inside in order to protect themselves against the most primitive experience of dissolution. This is the form of magical control which is based on desperate attempts of omnipotence and which leaves the individual highly vulnerable to all forms of collapse.

We can question whether any belief system or practice acts to enhance or to destroy its object. Perhaps, more correctly, we might ask what use an individual or a group makes of any given process? Even psychoanalysis may be questioned in this way. Whereas one person may use the potential experience offered by a certain structure in a way that allows some shift away from a previously more defined, pathological system, another person or the same person at another time may use that opportunity to lend power to his/her destructive wishes, thereby letting go of all brakes and speeding rapidly towards inevitable chaos.

At this stage it might be helpful to look at the way in which magic and magical thinking are explored in the psychoanalytic literature. Rycroft (1968) defines magic as:

Primitive, superstitious practices based on the assumption that natural processes can be affected by actions which influence or propitiate supernatural agencies or, as in the case of sympathetic magic, by actions which resemble those which the magician wishes to induce.

(Rycroft 1968)

Freud (1960) said that magic must subject natural phenomena to the human will. This definition contains within it one of the core conflicts of patients with severe eating disorders who subject their bodies to the will of their minds. These patients must have absolute control over natural bodily processes. Since they have not achieved a completely integrated sense of their body and mind, they become excessively dependent upon some external regulator to compensate for what is experienced as a state of internal deficiency. Emotional deprivation which was experienced at an earlier stage may be translated by the anorectic, for example, into active deprivation of herself. Rather than being a passive victim, this time at least she feels in control. The bulimic via the symbolic equation of food and nurturing, attempts to supply for herself what was missing.

Freud described the infant’s need to use magical thinking as a way of satisfying wishes, at first in an hallucinatory manner. He claimed that belief in the omnipotence of thought underlies all magical ideas and that magical acts are performed in response to specific motives. By making the distinction between primary and secondary processes in thinking we can begin to understand some fundamental links for the patient with an eating disorder. Primary process thinking arises from the desire to satisfy urges and drives and is not bound by logic, by temporal and spatial concepts or even by verbal representations. This aspect of thinking, which occurs in the unconscious, tends to be pictorial and not symbolic. In later stages of development, as secondary process thinking develops, the psychological drive shifts away from the motives of the act to the act itself. This helps us to understand the way in which the ‘magical act’ is carried out. For example, the act of vomiting in itself begins, after some time, to carry far more significance than purely emptying the stomach of unwanted food. This shift results in an idea which is often held by these patients, namely that an act in itself somehow determines the result in a magical way. Krueger (1989) describes this process: ‘incorporating symbolism and magical thinking [was] summarized by a patient who said, “It’s like I have anything and everything I’ve always wanted when I’m in the middle of a binge”’.

Freud was an important contributor to the much criticized but now established belief in the link between the principle of omnipotence in thoughts and the animistic mode of thinking. He compared primitive humans’ magical thinking with the logic of schizophrenics and concluded that the same form of thought, in which there is no clear distinction between what is specific to the ego and what is foreign to it, was to be found in children and in other disturbed adults. This has led to debate about the mental functioning of ‘primitive’ humans being based upon similar principles to those governing the earliest, most ‘primitive’ stages of child development in western, non-tribal societies. This is a highly complex area. At issue is not so much the question of the universality of human psychological development but rather the meaning which may be attributed to the way in which any group or individual functions. In the minds of many people, there is an association between primitive humans’ belief in the power of their wishes and the psychoneuroses of modern humans.

Although many of us today might propose that magical beliefs, shamanism or spells have been replaced by ideas more conducive to a western, post-industrial, scientific society (for instance, in the realms of physics, medicine or psychoanalysis), there are countless examples of ways in which magical beliefs still dominate areas of society (e.g. religion) and individuals within that society.

Another significant writer on the place of magic in the psychological development of the human infant is Jean Piaget. In his book, The Child’s Conception of the World (1929), he refers to a concept called ‘participation’. This implies a relationship between two things or two people, that are partially identical or have direct influence upon each other even when there is no spatial or intelligible causal connection between the two.

Participation is the key feature of magical thinking, that is, of the ways in which people attempt to modify reality. This type of thinking has been described as ‘pre-conscious pictorial thought’ and involves an equation of the object itself with its representative (i.e. in an idea or an image). Thus, what happens to one will happen to the other. In magical practices it is believed that affecting an external object which is identified with a person causes that person to be affected too.

Magic relates closely to symbolic function. Symbols within magical ideas appear to be participatory and for this reason magical thinking is viewed as utilizing a pre-symbolic mode of thought. Piaget describes the evolution of magical ideas as following a certain law in which

Signs begin by being part of things, or suggested by the presence of things in the manner of simple conditioned reflexes. Later they end by becoming detached from things and disengaged from them by the exercise of intelligence…between the point of origin and that of arrival, there is a period during which the sign adheres to the things although already potentially detached from them.

(Piaget 1929)

Thus, certain behaviours may originally contain no magical element but merely be simple acts of protection. However, with repetition, these acts lose their rationale and become a ritual which in itself performs the desired function. The actions become the cause as well as the sign or symbol. For example, the infant’s cry may lead to some action on the part of the mother. A continuity is created between her activity and that of the baby’s. The more the environment responds to the baby, the greater his/her sense of participation. Similarly, the discovery by the baby that his/her limbs can move at will may imply that he/she can command the world.

Piaget’s contribution to magical thinking is of great importance. He summarizes the magical practices of children as: (a) occurring through the participation of actions and things (where action influences an event); (b) occurring between thought and things (where reality is influenced by thought); (c) occurring between objects themselves (two things must not touch each other); (d) occurring through the participation of purpose. In other words, objects are regarded as living and purposeful, that is, animistic. According to Piaget, if a child believes that the sun chooses to follow him/her around, this belief is animistic; however, if the child thinks that it is he/she who can make the sun move, this idea is founded upon magic and participation.

Freud stated that the animistic mode of thinking, the principle of omnipotence of thoughts, governed magical ideas. It was this that led him to associate these ideas with the internal world of primitive humans, for which he has been sharply criticized. Freud believed that primitive humans (likewise neurotics) had immense belief in the power of their thoughts. Piaget opposed this, distinguishing between the participation and magic of primitive humans and that of both the neurotic and the child.

Freud considered magic to precede animism. In Totem and Taboo, he differentiated between the two by suggesting that, whereas magic reserves omnipotence solely for thoughts, animism hands over some degree of it to spirits, and so prepares the way for the construction of religion. How these concepts affect normal human behaviour is more fully understood when considering their presence in everyday thought. Piaget examined ways in which the boundary between the self and the external world may become blurred, for instance in the case of a listener feeling the need to clear his/her throat when hearing the speaker’s husky voice. One could find numerous examples, particularly in states of daydreaming, anxiety or fear. At times of great stress, the attempt to maintain or grasp reality may itself induce some magical thinking or ideas.

For Piaget, animism, as distinct from magic, was the product of participation which a child would feel to exist between the child and his/her parents. Through being unable to distinguish psychical from physical, every physical phenomenon appears to the child to be endowed with will. The distinction between thought and the external world is therefore seen to evolve gradually. The projection of mental relationships into external objects is experienced as concrete and real.

I initially encountered animism in one of the first patients I worked with who suffered from an eating disorder. The 28-year old woman had collected dolls over a number of years. She now had over two hundred and she attributed to each one specific personality characteristics. She would respond to her dolls quite concretely, rewarding them as appropriate. One doll had the power to make her eat (against her will). Only by setting fire to this doll could she prevent its powerful influence. This was a clear example of how behaviour can be related to magical ideas.

The theories of Freud and Piaget offer complementary ideas from psychoanalytic thought and developmental psychology regarding magical thinking. Whereas Freud’s psychoanalytic theory of development describes the special affective condition underlying magical beliefs as resulting from narcissism, Piaget thought that this state resulted from an absence of any consciousness of the self. Freud describes the child at this stage as being solely interested in him/ herself, in his/her own desires and thoughts which seem charged with a special value. In Piaget’s view, if the infant believes in the all-powerfulness of thought, he/ she cannot therefore distinguish his/ her thought from that of others or his/her self from the external world.

Religion, like art, utilizes the mechanisms of Freud’s primary process thought to give structure to abstract concepts. The use of concrete thought is very often culturally sanctioned. Many early religions tended towards the mechanisms of concretization. Within Judaism one can trace a gradual move from paganism to monotheism, which was then adapted by the rest of the world and which involved progressive shifts away from concretization. Indeed, the western tradition of magic is also linked historically to Jewish influences. Although private, personal magic is condemned in the Old Testament, authorized magic was frequently worked by the prophets such as Moses parting the Red Sea. A simple example of the concretization of the expulsion of evil is provided by the ritual in which the sins of the whole community were heaped upon the head of a goat, which was then cast out on the Day of Atonement.

The dual nature of people’s attitude toward magical practice and belief is equally well represented by the Old Testament. Jewish magic (actually a combination of Mesopotamian, Egyptian and Greek elements) had a wide reputation in the ancient world, as portrayed by King Solomon who owned a magic ring and understood the language of the animals and birds. On the other hand, Isaiah condemned the mediums and wizards who chirped and muttered.

A number of authors have compared and contrasted the anorectic and the saint. This is a fascinating concept and contains the seeds of much of what will be discussed later. Selvini Palazzoli (1974) declares that the asceticism of the anorectic should not be confused with that of the religious:

the saint becomes ascetic not as an end in itself but as a means to attain mystical communion with God…Anorectics do not become ascetics after a slow and arduous process of inner development.

(Selvini Palazzoli 1974)

Magical thinking may be demonstrated by describing a bulimic patient in a particular art therapy session. This patient started painting in a state of heightened stimulation. She explained that she had just had a telephone conversation with her mother, during which she had felt punished for deciding not to visit her mother the following weekend. Before painting, she had asked with some emotion, ‘How can I ever lead my own life if she constantly makes me feel so guilty for it?’ I suggested that she put some of these feelings on to paper. After sitting rigidly for a few minutes, she chose the largest sheet of paper available and then, rather than squeezing the paint from the bottles on to palettes, she gathered up as many bottles as she could in her arms and began frantically pouring the paint directly on to the paper. After watching this for some time, I intervened. ‘You’ve been expressing how this makes you feel. Now how about making an actual picture, using parts of what has come out already?’ She went on to cut out parts of the thick mess and to stick these on to another piece of paper. She then began to paint an image of one person inside another.

Expressing her rage, through the pouring of the paints, brought this patient near to tears. The sadness was connected to her associations not only with bingeing in this state but also with the unbearable experience of feeling so enraged with the very person upon whom she felt dependent, a position forcing her to recognize her separateness. The furious merging of all of the colours seemed to me to be a frantic attempt to deny this separateness, to achieve union and to satisfy ‘all that she had ever wanted’. The question of whether to spend the weekend at her mother’s home or to ‘lead her own life’ mirrored her true struggle and the punishment that she felt for choosing to ‘reject’ her mother served to create a conflict which made it yet more difficult for her to ‘leave home’. The initial use of the materials was in effect a magical attempt at control. The materials became endowed with a life of their own. The painting takes on a transitional quality as the different materials are experienced in an animated form. This process also occurs for the patient with an eating disorder in her relationship to food.

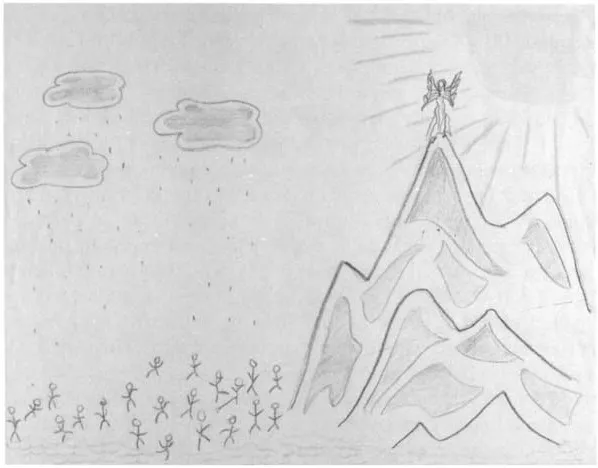

I have seen numerous paintings made by patients with eating disorders in which they, or some substitute which they recognize to be a symbol of themselves, are sitting on mountain tops, on coulds or in heaven and are looking down at earthlings. The paintings, which are complemented by fantasies of omnipotence, ultimate control and ensured safety illustrate the position of the all-seeing untouchable, unreachable disembodied spirit (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1

This god-like posture performs an important function in the relationship that these patients have with their own bodies. For the anorectic, the counting of calories may itself create the required safety and security. The action develops into a magical means of protection, in that the symbol remains attached to what it represents. The symbol of the skeletal body becomes attached to such concepts as helplessness and demarcation from others. To change (i.e. to give up) this ‘frame’, the anorectic is giving up not simply a symbol for the self but the actual self.

The individual with an eating disorder cannot bear t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Introduction

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- References