This is a test

- 308 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Making no assumption of your prior knowledge, Economics introduces the basics of economics as they relate to the built environment. Looking at the principles of microeconomics (markets, price mechanisms, resource allocation, theory of the firm, etc.), these principles are put into the context of construction firms and property markets. Lively, real-life case studies are built into the text to provide concrete examples of the theories being explained and macroeconomics are also covered.

Key features of this easy-to-use book include:

- clear chapter structure

- tutorial questions linking the case histories to basic principles

- extracts from newspaper and journal articles to show the relevance of economics to the construction industry

- 100% construction orientation

- a useful bibliography, glossary of economic terms

- preview questions at the start of each chapter and exercises and discussion topics at the end to test your understanding.

Economics will enable you to understand the working of economic forces as they relate to the construction industry.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Economics by J.E. Manser in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture Methods & Materials. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Why economics?

PREVIEW

Economics is about making choices. Individuals, groups, businesses and nations are constantly having to choose how to use their resources. Can I afford a holiday abroad this year, or would it be better to get a new car? Should the firm invest in the latest in mini-excavators, or would it be better to buy more scaffolding? Is the Department of Transport’s bid for new roads going to succeed at the expense of the Education Department’s claim for more schools? If we had sufficient resources to satisfy all our wants, economics would vanish, but we never have enough resources for everything we want to do. So we economize, we make choices.

It is not simply a lack of money that limits what we can have. The government could easily print more money, but this would not help us. Money is only an IOU—a banknote is a written promise to pay the bearer a certain sum. It has value only in so far as we can redeem it, which means in so far as we can exchange it, use it to buy things, goods and services. It is our enjoyment of these which determines how well off we are. Standards of living are measured largely in terms of consumption.

What we consume depends not just on incomes, but on what is produced. If the government were to pass a law to double everyone’s income there would not be any more goods in the shops for you to buy You might have more money to spend, but so would everyone else. Stocks of goods would soon start to sell out and suppliers would raise their prices. In real terms we would be no better off.

SCARCITY, CHOICE AND COSTS

A higher standard of living means producing more goods. But production cannot be increased indefinitely. Limits are imposed by what resources are available, that is the skills of the workforce, the machinery they use, the raw materials, the energy and all the other inputs necessary to making the things we want to enjoy. (Sometimes resources are not fully used, in which case our economy will produce less than it could, but there is still a limit on what is possible.)

Limits on the resources available force us to make choices. More of one thing means less of another. This is what economists call scarcity, meaning simply that there is not enough to allow for everyone to consume freely as much as they would like. In cases where this sort of plenty does exist, for instance the air we breathe, no choices are necessary. Such items are called free goods. Free goods may be vital to our wellbeing, but they are not important to economics because production and consumption do not involve sacrificing alternatives. If I put my tomatoes in the sunshine to ripen the fruit, it does not mean there is any less sunshine for you to enjoy. Some free goods, like clean air, we take so much for granted that we are in danger of misusing them to the point where they may cease to exist in sufficient plenty for all to enjoy! At this point they too become scarce and their use poses economic questions.

Rainfall is another example of nature’s bounty, which may be treated as a free good where it is in ample supply. The rain that falls freely on my crops also falls on my neighbour’s—but a decision to build a storage tank for the rainwater means that it ceases to be a free good. It now becomes a stored water supply and so enters the realm of economics, of choices between alternatives.

Decisions have to be made. How much time should be given to building the tank? What materials should be used? Where should it be placed? How big should it be made? These questions are partly technical, involving issues such as the permeability of different materials and the design of the structure, and partly economic, involving questions about the most efficient use of resources. What is the cost and availability of different materials? How much time is it worth spending on the project? Time and materials used to build the tank cannot be used elsewhere. Once the task is completed, a free good, rain, is transformed into an economic good, something which is scarce, namely a stored water supply.

Further choices have to be made concerning the distribution of the goods. Who will benefit from this water supply? One basic decision about its allocation has already been taken: by storing the water, run-off is reduced, so there is more water for the household with storage tanks and less for households lower down the valley. Very often when we make choices that will benefit ourselves we find those choices also affect other people, sometimes adversely.

How shall the water be used? For irrigation, for drinking, for cooking, washing and cleaning? The supply is limited, the potential uses almost endless. Every litre put to one use means a litre less for some other use. Making choices implies making sacrifices, going without the alternative possibilities. This is an inevitable consequence of scarcity and economists use the term opportunity cost to emphasize this fact. Building the tank used resources—labour, materials and space—which could have been used in other ways (to build a grain store perhaps, or hen houses) but which are now committed and no longer available for other uses. Hence the water supply was created at the cost of sacrificing other possibilities: it has an opportunity cost; there is a price to be paid for the water—it is no longer free.

Students are generally very familiar with opportunity costs. Expensive textbooks compete with rent demands and the attractions of a night out on the town for the student’s limited income. More money would solve some problems, but not all. There is another scarce resource, time! Managing time is as much an exercise in opportunity costs as managing a budget—the ‘price’ of a night on the town may be a rushed assignment and lower grades.

THE PROCESS OF PRODUCTION

Resources used to produce goods and services are called factors of production. They are classified under three headings: land, labour and capital. Land includes all natural resources—not just the earth’s surface area but also the mineral deposits, forests, fisheries and so on provided by nature. Labour is the human effort employed in production, including managerial and administrative work as well as manual labour. Capital is the stock of man-made resources which have already been produced. It is the accumulation of tools, machinery, buildings, transport systems, etc., that we have manufactured to help us work more effectively and so increase our current output. As such, capital itself embodies past decisions on opportunity costs. The task of deciding how to combine these three elements, what goods to produce and which production methods to use, is termed enterprise. Some economists classify this as a fourth factor of production, others regard it as no more than a subdivision of labour.

The whole process of production is designed to provide utility, which means it is aimed at satisfying our wants. Utility cannot be measured objectively because people’s needs and desires are individual. A beefsteak has no utility for a vegetarian, nor a cigarette for a non-smoker. But wherever a want is satisfied, whether it is a basic need or something entirely frivolous but fun, utility is created. This means that production involves more than the manufacture of goods.

All manner of services which contribute to consumer satisfaction are part of the production process. Consumers in Southampton or Edinburgh cannot enjoy their favourite TV programmes on sets still stacked in a Welsh warehouse. Utility is not created until the consumer’s wants are satisfied, so the transport, insurance, advertising, stockholding and display of the goods in shop windows are all part of the production process. Similarly direct services, such as banking, hairdressing, education or entertainment, are all forms of production, helping to meet consumer needs and satisfy consumer wants.

Economic questions face us daily. As individuals we seek to maximize utility. Limited incomes mean choosing among the many goods and services available. Businesses, seeking to maximize profits, also have to decide between alternative courses of action—from the basic choices of what sort of goods to sell, through to detailed issues of design and production, all of which will have implications for the way they use resources.

A builder may decide to concentrate his efforts on house building, thereby sacrificing the opportunity to work on shops, offices, etc. This is only the first decision of many. What type of house should be built, which materials should be used, are traditional building methods preferred, or would pre-fabricated units be better, should the property be sold or let? Traditional bricks and mortar construction requires a different mix of materials and more labour than timber-frame or pre-cast concrete. Costs will vary, a fact which has implications for who will buy the houses, or, in other words, for the distribution of the goods.

Economics is the study of this process of using resources to satisfy wants. Are we managing to maximize utility? Are we using our resources in the best possible way? Could we, by making different choices, achieve a higher standard of living? What constraints limit us? Who should decide how we allocate resources between competing industries, and how to distribute goods amongst different members of the community? A brief consideration of these questions will raise many issues fundamental to economics. It also raises questions about the relationship between economics and politics. We will return to this in the next chapter.

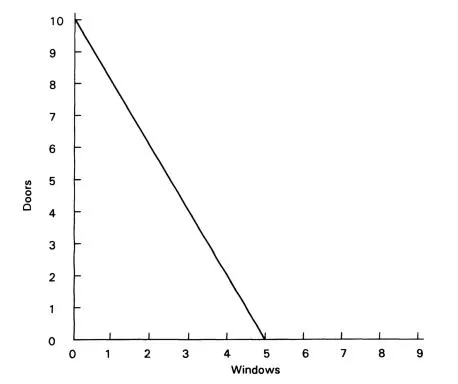

TRANSFORMATION CURVES

We have already seen that the production of all goods and services involves an opportunity cost. If we want more of this we must take resources away from something else and have less of that. If a builder chooses to construct sheltered accommodation for the elderly, the land, labour and materials he uses will not be available to build homes for first-time buyers. The decision to put in a bid for this contract rather than that one, if successful, will mean the firm’s resources are tied up and they will not be able to take on other work for the time being. This may mean sacrificing some potentially profitable opportunities. The entrepreneur must constantly weigh up the alternatives.

Figure 1.1

Transformation curve.

A transformation curve is a graphic representation of this opportunity cost. Along the two axes are measured quantities of the alternative goods which could be produced from a given quantity of resources. A joiner, for instance, can use his labour, tools and materials to produce doors or windows. The transformation curve plots all the different combinations of output which the joiner can achieve, showing the ‘trade-off’ between t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- ALSO AVAILABLE FROM E & FN SPON

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Dedication

- Using this book

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Why economics?

- 2 Economic systems

- 3 The market mechanism

- 4 Factor markets: land

- 5 Factor markets: labour

- 6 Factor markets: capital

- 7 Competition and monopoly

- 8 Theory of the firm

- 9 Profit maximization

- 10 Size of firms

- 11 The construction industry

- 12 Competition and pricing in the construction industry

- 13 Forms of business organization

- 14 Marketing

- 15 Productivity

- 16 The workforce

- 17 Capital equipment

- 18 Land and site values

- 19 Financing the firm

- 20 Externalities and cost-benefit analysis

- 21 The national income

- 22 The money supply

- 23 Housing policy

- 24 International trade

- Glossary

- Further reading

- Index