1

READING THEORY PERSPECTIVES

INTRODUCTION

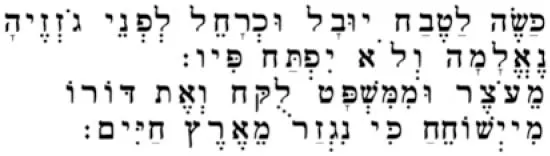

Suppose for a moment that you are an American visitor to Jerusalem in the Roman Palestine of the mid-first-century AD. It is morning during the dry season. The Mediterranean sun shines brightly. You decide that it is a good day to go to Gaza to see what is new by way of caravan imports from Egypt. So early in the morning, with sea breezes still cool in the hills, you begin the seaward walk down from Jerusalem on the Gaza-Jerusalem road. Not too far in front of you, you see a person walking, going in the same direction as you are. Suddenly you hear a man’s voice coming from over a rise in the road. That voice says something that sounds as follows:

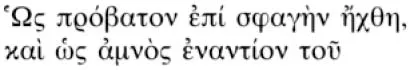

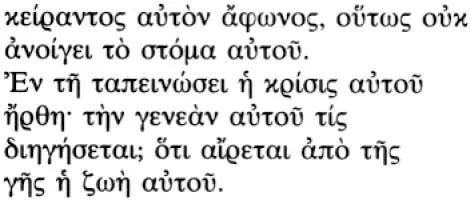

Obviously what you have just heard are not the squiggles you see written here. Rather what you have heard were sounds, strange sounds, sounds as strange as the above squiggles. You notice now that the man in front of you also stops. You go up to him and ask: “What did that mean?” He shrugs his shoulders in response. Obviously he does not understand English. So you open your arms, shrug your shoulders and throw your head back slightly in that Mediterranean gesture that means: “What is going on, then?” Light dawns in his eyes and he proceeds to tell you:

Again, you get a downpour of strange sounds, indicated here by the strange squiggles used to write down those sounds. By now, you figure out that what the man is telling you in his strange sounds is his version of the sounds you both heard.

It should occur to you by now that you are a foreigner in a foreign land where a familiar thing such as conversing with someone in English is equally alien. Now, what would you need to understand your friendly fellow traveler? How would you get to understand his strange sounds? I suggest that the way to come to understand your first-century acquaintance is not unlike the way you would get to understand a contemporary foreigner who does not know English, yet with whom you wish to communicate. Furthermore, I suggest that trying to understand a writing such as Luke-Acts involves the same procedure as attempting to understand foreigners speaking to you in their own language. Only in the case of Luke-Acts, as with the example above, you are the foreigner. For, any historically sensitive reading of New Testament writings necessarily puts the reader in the role of a stranger in that extremely strange and curious land of the first-century eastern Mediterranean.

The authors of the biblical writings as well as the persons they portrayed all came from this region. They wrote their books in those strange squiggles we call the Hebrew and Greek alphabets. And these strange squiggles all stand for extremely strange patterns of sounds quite alien to most US ears. How would one get to understand such strange sounds and read the alphabets that stand for those sounds? Would it be sufficient to transcribe your informant’s sounds into our own alphabet? If you did so, it would look as follows:

Hos probaton epi sphagen echthe, kai hos amnos enantion tou keirantos auton aphonos, houtos ouk anoigei to stoma autou. En te tapeinosei he krisis autou erthe.

Ten genean autou tis diegesetai? hoti airetai apo tes ges he zoe autou.

Even in our own alphabet, there is not much that looks familiar. Does the statement sound any more familiar if you try to read it?

Moreover, would a translation of the Greek give you the meaning of what your fellow traveler intended to tell you? The Greek translates out as follows:

As a sheep led to the slaughter or a lamb before its shearer is dumb, so he opens not his mouth. In his humiliation justice was denied him. Who can describe his generation? For his life is taken up from the earth.

Does this translation tell you what the statement means? If you looked in a biblical concordance, you would find that this passage is from Acts 8:32–3 and quotes Isa. 53:7–8 in a Greek translation such as the one your travelling companion gave you. Does that help you understand what is going on now? If you read the passage in Acts 8, you will find out that the one whose voice you initially heard was a black man, probably a proselyte of the house of Israel on pilgrimage to Jerusalem. He is described as a eunuch from the court of Queen Candace in Ethiopia. You will likewise find out that the person from whom you inquired about what was being said was a follower of Jesus of Nazareth named Philip. His Greek name might tell you why he preferred to talk to you in Greek. In Acts, Philip is described as a “deacon.” Now that you have a name, social role, some minimal information about the words you heard and basic geographical and chronological orientation, can you interpret the passage translated above?

If other people knew only your name, social role, some of your statements and some geographical and chronological information about you, would you say that they can now really understand you? If they had some minimal information about an esoteric book you might be reading, would that suffice to help them understand that book and why you are reading it? What more would they have to know? Would a story of your family history suffice now? Would a story of your life help?

Notice that these questions cover the who, what, when, where and how of the situation. They have not raised the why question, the question of meaning. Why read a passage from Isaiah on the road? Why the need for a Greek translation? Why the social role of an Ethiopian official, why the subsequent behavior of Philip? And if we stick to the passage itself, why the mention of lamb and sheep? Why humiliation? And in a Christian writing such as Acts, why this passage from the Israelite religious tradition in Isaiah? The answers to all these questions require historical information of the who, what, when and where sort. But to find out the why, the meaning of it all in the lives of people, requires information from the social system of the time and place of the original audience of this work.

To read Luke-Acts as we propose to do in this book requires familiarity with the social system presupposed by and conveyed through the language patterns that are presented in the Greek squiggles of the Greek texts. As we shall have occasion to indicate, the meanings people share are rooted in and derive from a social system. “Social system” refers to the general ways in which a society provides its members with a socially meaningful way of living. The social system includes (1) culture, i.e. the accepted ways of interpreting the world and everything in it; (2) social structures, i.e. the accepted ways of doing things such as marrying, having children, working, governing, worshiping and understanding God; and (3) accepted individual self-understanding, accepted ways of being a person. People use language to have some effect on each other in terms of the meanings that constitute the social system. And people learn those meanings along with the language of their society in the process of growing up in that society.

Incidentally, why do we presume that the strange alphabet of the Greek New Testament can be understood at all? It seems that as a rule human beings continually find patterns everywhere they look, and they invariably find some meaning in those patterns. In the above example, the voice you heard clearly sounded as though it followed some pattern of cadence and articulation. It was not a scream, shriek, moan, groan or any other sort of unpatterned sound. If it sounded patterned it must have been communicating meaning of some sort. Or so one would logically conclude. The response to your quizzical gesture produced another shower of sound that surely sounded patterned with cadence and articulation. Again, it seemed clear that the man was saying something intelligible. His utterance sounded like it should be conveying meaning of some sort because it was clearly patterned (Johnson 1978:3–7).

The case with squiggleson a page is quite similar. Look at the Hebrew and Greek passages printed above. While they are not English, they are surely not the chaotic doodlings of a 2-year-old claiming to write something. They seem to be patterned and to follow a definite sequencing. The presumption which most humans share about patterned soundings and squiggles is that they convey meaning in some way. They are intended to communicate something to another human being. How? Reading is learning how to see patterns in the squiggles. Such patterns are called wordings. The wordings, in turn, reveal meanings,but only on condition that we share the same social system as the persons who initially wrote the squiggles. A translation of Luke that simply says his words in terms of our words hardly mediates the meaning of the Greek text, the meaning of Luke and his audience. The reason for this is that meaning is not in the wordings. Rather meaning is in the social system consisting of individual persons and their individual psychological and physical being, which is held together by a shared culture, shared values and shared meanings along with social institutions and social roles to realize those values and meanings. For example, take a basic New Testament Aramaic word such as ’abba(translated into Greek as pate¯r,and into English as “father”). Would the English, “father,” fill you with the meanings which a first-century Palestinian, Israelite native speaker thought and felt with this word? Frankly, no! Again, I suggest that for a native English speaker who has never lived in an Israelite, Aramaic-speaking community, the word ’abbaalways means the very same thing as the English “father,” since it invariably refers to the roles, behaviors, and meanings ascribed to US fathers. The only way to get “father” to really mean what an Israelite, Aramaic speaker such as Jesus might have meant by ’abbais to get to know the social system within which the role of ’abbaworked (see Elliott 1990:174–80; Malina 1988; Barr 1988). The reason for this is that what people say or write conveys and imparts meanings rooted in some social system. The purpose of this chapter is to explain why this is the case and what that might mean for our understanding of that human skill called reading.

For literate people, the process of reading is often taken for granted, much like seeing or hearing. Few people reflect upon that set of behavioral skills picked up most often in elementary school. Yet access to the Bible in general, and to the books called Luke-Acts in particular, is totally dependent upon reading. Not a few readers innocent of what the reading process entails share a variant of what the computer-literate would call the “WYRIWYG” viewpoint (What You Read Is What You Get). We call this the fallacy of the “immaculate perception.” Such naivety can be found among both professional and non-professional students of the Bible, just as it can among those whose access to primary sources of information requires reading (for example, historians and literary critics of all stripes). The presumption that what one reads derives directly from the writing that one confronts is a presumption founded on the belief that writings are objective objects, simply “out there,” and are to be handled like any other objects such as rocks or sticks. Such a presumption disregards the developing psychological uniqueness of the reader (called subjectivity). And it also disregards the reality that makes communication with language possible at all, that is, the social system shared by readers and their social groups as well as writers and their social groups.

To immerse the subjective and social dimensions of human being within some all-encompassing objectivity is to condemn a person to perpetual ethnocentrism and anachronism. For the simple fact is that the squiggles on the page (regardless of alphabet) have to be deciphered somehow into articulate and distinct patterns by a reader to give access to the meanings communicated through the squiggles by the author. If reader and writer share the same social system, communication is highly probable. But if reader and writer come from mutually alien social systems, then as a rule, non-understanding prevails, as is the case above where you, the reader, are the stranger in a strange land. Should a translation of the wording (words and sentences) be offered, apart from a comparative explanation of the social systems involved, misunderstanding inevitably follows. In other words, should there be a person available to turn the squiggles into sounds, these sounds too need to be decoded by a hearer to gain access to the sender’s meanings—again, provided both share the same social system.

This description of hearing and reading a text might sound rather involved. However, it is truly necessary both to dispel the naive objectivism of the “Take up and read!” variety and to facilitate considered analysis. Reading is not simply sounding out the squiggles written or printed on a surface. I am acquainted with persons who can sound out what I know to be Polish or Hebrew or Greek or Latin without understanding much or anything of what they so readily perform. Reading is not simply turning markings into soundings. Rather, reading always involves decoding the markings and/or soundings into the wordings and, finally, having the wordings yield the meanings they convey from some author or speaker in a specific social system.

This may all sound like another Teutonic belaboring of the obvious, yet it bears emphasizing since nearly all interpreters of the Bible, professional and non-professional, take the reading process for granted. Further, one often gets the impression that these interpreters all too innocently assume that the categories of their elementary school grammar, generally learned at the concrete stage of human cognitive development, are categories that refer to concrete realities. Thus the letters, words and sentences of spoken language are presumed to be concrete, meaning-bearing, linguistic entities. After all, when we write down what we say, do we not put down concrete letters, words and sentences? And these concrete words and sentences are presumed to have meanings that are directly accessible to people by the simple process of learning to look at them. The process is not unlike collecting concrete, individual stamps, coins and butterflies.

But is this in fact the case with language? Is not language a flow of patterned soundings articulating wordings and expressing meanings? Are not words and sentences deriving from the level of wordings arbitrarily set apart into discrete entities? Are not words and sentences in fact abstractions and ideas treated as concrete things? Are they not then “thingified” concepts created by ancient and modern grammarians and lexicographers to facilitate their logical analyses of human thinking, a dubious enterprise at best (Fishman 1971:91–105)? People in fact do not utter words. Rather they utter a whole tissue of patterned, articulate and cadenced sounds which the literate grammarian breaks into smaller repeatable pieces. The full segments of sound are wordings. The smaller repeatable pieces of sound are set apart like cells in a culture dish and called words. Illiterate persons are not aware that they speak words. When asked to repeat a word, illiterates invariably begin at a point which they consider the beginning of their previous utterance (Lord 1960:99– 138; Ong 1982:31–77).

If words are not the locus of meaning, neither are language systems as such. In spite of the fact that modern Greek and Hebrew speakers can express the world of contemporary society and science quite well, there is still the suspicion that “biblical thought” is different from our own, because of the nature of the languages of the Bible. This is the much-quoted Whorfian hypothesis applied to the Bible. In the 1940s, B.L.Whorf advanced the hypothesis that cultural differences including ways of reasoning, perceiving, learning, distinguishing, remembering and the like are directly relatable to the structured differences between languages themselves (see Whorf 1956). For example, the tenses of the Hebrew verb would make ancient Israelites perceive the reality of time in a distinctive way. The sociolinguist Fishman notes (1971:92): “Intriguing though this claim may be it is necessary to admit that many years of intensive research have not succeeded in demonstrating it to be tenable.” As reading theory indicates, it is not to the structured differences between languages that we have to look, but to the social systems of different peoples.

READING

Every theory of reading presupposes a set of assumptions concerning the nature of language and the nature of text. How does language work? How does text work? And how does reading work? It is quite apparent that written language does not live in scrolls or books. The markings on a page stand for wordings that represent meanings that can come alive only through the agency of the minds of readers. Before setting out a model of describing what happens when a person reads, I shall begin by setting out some assumptions about language and text.

On language

There is an explanation of the nature of language that is rooted in the presupposition that human beings are essentially social beings. Everything anybody does has some social motivation and some social meaning. From the point of view of this approach, the chief purpose of language is to mean to another, and the purpose of this meaning is to have some effect on another. This perspective is often called sociolinguistics.

The approach to sociolinguistics adopted here derives from Michael A.K.Halliday (Halliday 1978; see also Cicourel 1985). In this perspective, language is a three-tiered affair consisting of (a) soundings/spellings that (b) realize wordings that (c) realize meanings. And where do the meanings realized in language come from? Given the experience of human beings as essentially social beings, those meanings come from and in fact constitute the social system. This three-tiered model of language wo...