eBook - ePub

Russians in Britain

British Theatre and the Russian Tradition of Actor Training

This is a test

- 218 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

From Komisarjevsky in the 1920s, to Cheek by Jowl's Russian 'sister company' almost a century later, Russian actor training has had a unique influence on modern British theatre. Russians in Britain, edited by Jonathan Pitches, is the first work of its type to identify a relationship between both countries' theatrical traditions as continuous as it is complex.

Unravelling new strands of transmission and translation linking the great Russian émigré practitioners to the second and third generation artists who responded to their ideas, Russians in Britain takes in:

-

- Komisarjevsky and the British theatre establishment.

-

- Stanislavsky in the British conservatoire.

-

- Meyerhold in the academy.

-

- Michael Chekhov in the private studio.

-

- Littlewood's Theatre Workshop and the Northern Stage Ensemble.

-

- Katie Mitchell, Declan Donnellan and Michael Boyd.

Charting a hitherto untold story with historical and contemporary implications, these nine essays present a compelling alternative history of theatrical practice in the UK.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Russians in Britain by Jonathan Pitches in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Acting & Auditioning. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A Tradition in Transition

Komisarjevsky’s Seduction of the British Theatre

To know how to direct acting one must know what acting is and how to teach acting.

(Komisarjevsky, Play Direction: Short Synopsis of Lectures, Harvard Archive)1

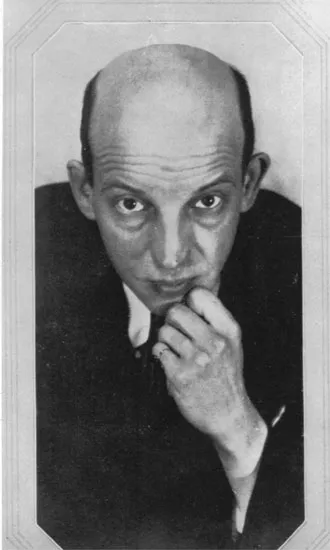

Of the many influential Russian émigrés to have had a tangible impact on the British theatre tradition over the last century, Theodore Komisarjevsky (Figure 1.1) deserves special recognition. Whereas Michael Chekhov’s legacy is built upon just three intensive years at Dartington from 1936 to 1939, Komisarjevsky worked for two decades in the UK (1919–39), directing scores of productions from London to Leeds to Glasgow, and culminating in a series of epoch-defining productions at Stratford’s Shakespeare Memorial Theatre, before the Second World War. By the time Maria Germonova’s splinter group of the Moscow Arts Theatre – the Prague Group – arrived in London in 1928, claiming to be continuing the Stanislavsky tradition and, according to Germanova’s letter to The Times, ‘interpret[ing] it to audiences in Western Europe’,2 Komisarjevsky had been practising as a director and teacher in Britain for almost ten years and had already earned a career-defining reputation for his own sensitive interpretations of Chekhov’s plays. Whilst Meyerhold’s purple period of theatrical work was appreciated from afar in the UK – and disseminated in publications such as Leon Moussinac’s (1931) The New Movement in the Theatre – Komisarjevsky was producing Le Cocu Magnifique and The Government Inspector in the nation’s capital, the latter with a young and impressionable Charles Laughton in the role of Osip, the servant. Komisarjevsky even beat his Russian compatriots to the British bookshops, publishing his Myself and the Theatre (Komisarjevsky 1929) with William Heinemann seven years before An Actor Prepares appeared courtesy of Geoffrey Bles and four years before Richard Boleslavsky’s Acting: the First Six Lessons came out in Theatre Arts Books.3 Indeed, as the first Russian practitioner operating in Britain, after the formation of the Moscow Art Theatre, Komisarjevsky can profitably be thought of as the British-based equivalent of Boleslavsky in the States,4 at least for the many acting ensembles with which he worked in the 1920s and 1930s.

Figure 1.1 Portrait of Theodore Komisarjevsky in London. Source: Burra Moody Archive.

From a number of angles, then, as a critic, a director and a teacher, Komis – as the British theatre establishment began to call him – had a demonstrable impact on the tradition of acting in the UK before the Second World War. His writing, and particularly Myself, infiltrated deep into British (and American)5 theatre culture; his work as a director effectively initiated the British fascination with Chekhov before impacting decisively on the Shakespeare tradition thirty years before Peter Hall founded the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC); his teaching was no less significant and influenced a generation of British theatre actors who were perhaps the first to perform on a truly international stage: John Gielgud, Peggy Ashcroft, Claude Rains, Charles Laughton, Anthony Quayle, George Devine, Alec Guinness.

However, whereas there is good evidence of his productions (mainly from prompt copies, reviews and associated correspondence), and his three books,6 Myself, The Costume of the Theatre (Komisarjevsky 1932) and The Theatre and a Changing Civilisation (Komisarjevsky 1935) are still available for scrutiny, evidence of Komis’s pedagogy is far more difficult to tie down. He founded a theatre school in Moscow in 1913 before he moved to Britain, taught at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA)7 and, after moving to the USA, taught again at Yale. His acting studio ran for nearly fifteen years once he settled in the United States and he spent much of his later life (1944–54) planning a fourth book, specifically on acting. Accounts of his approach to directing indicate that when he had time to devote to a production he also used the opportunity to develop the ensemble’s skills. However, despite such a demonstrable and longstanding commitment to teaching, the evidence of what Komis actually did in the studio – his exercise regime, if not ‘system’ – is notable by its absence.

There are several reasons for this. One may simply have been the breadth of his vision. Komisarjevsky was a complete ‘man of the theatre’. A trained architect, he designed the sets, costumes and lights as well as directing the actors. As Anthony Quayle put it in an interview for Michael Billington:

He was a really remarkable man, a draughtsman and designer as well as a director. His was the entire and total concept. Even Peter Brook can’t do everything … Komis could.

(Billington 1988: 52)

Such theatrical polymathy meant that his priority or focus as a writer was never as clear-cut as was that of, say, Stanislavsky or Michael Chekhov, and this is reflected in his publication record, which includes writing on interior design, ballet, the history of costume and the socio-political context of theatre from the Greeks to the twentieth century.

A more significant reason for the lack of documentation of Komisarjevsky’s studio work was the absence of a documenter or scribe to record his lessons. Meyerhold relied on prominent students such as Aleksandr Gladkov to keep records; Michael Chekhov had a dedicated transcriber in Deirdre Hurst du Prey, who recorded almost every lesson at Dartington for posterity. The formidable practitioner collective of the First Studio (Vakhtangov, Boleslavsky, Suerzhitsky and a young Chekhov) had a book permanently open in their studio to document the day’s findings (Benedetti 1998: 15). Komis had no such system; he often led private one-to-one classes and when his collaborator and last wife Ernestine Stodelle was present she was likely to be co-presenting and therefore not best placed to record the sessions.

Another key factor in the lack of detail surrounding Komis’s pedagogy seems to be his reluctance actually to commit his ideas to paper, beyond the important sections on training in Myself and the Theatre and snippets from The Theatre, both of which will be analysed later. The long-standing correspondence Komis had with the British actress Phyllada Sewell from 1930 to 1954 illustrates this resistance very tellingly. The idea of a book to complement his other theatre-related publications is first mentioned in a letter from Komis in December 1944:

I have a few book projects in my mind. Probably they will remain in my mind forever, unless I win a couple of thousand in an imaginary lottery, and remove myself to an imaginary warm cottage in an imaginary land of quiet and dry warm weather.8

His pessimism proved to be accurate for, although Komis made reference to a book project in many other letters to Phyllada and engaged her partly in the brokering of a potential contract with the publishers of The Theatre, the Bodley Head, he remained stubbornly and strangely reticent when asked to expand on his ideas. The editor of the Bodley Head, C. J. Greenwood, for instance, received no reply when he asked the following (not unreasonable) question in a letter from 1950 pertaining to the project, now conceived as ‘a handbook for professional students & amateurs’:9

All you have told me in your letter is that the length would be about 100,000 words or more and that it would be on producing plays and operas, and how to do it … Would it not be possible for you to write me in more detail on the plan of the book: say a couple of pages describing exactly what you propose doing, together with a list of chapter headings. I imagine this must be pretty clear in your mind.10

If the contents of the book had been clear in Komis’s thinking four years before his death, then that is where they remained for they were never committed to paper. He did begin preliminary research for the study the following year, interestingly prioritising scientific research as his major source of inspiration: ‘I am reading books on psychology to know more about modern theories for my book on acting. It’s supposed to be the book for the Bodley Head man’,11 he wrote to Phyllada, capturing the acting zeitgeist in the United States at the time. However, the year after that, in September 1952, he was still promising to start it and professing to have forgotten all about Greenwood.12 By the time he died, two years later, there was no significant progress made on the book, not even any drafts, and thus a considerable gap in the understanding of Komisarjevsky’s contribution was created.

This chapter aims to address this gap, collating the significant circumstantial evidence relating to Komis’s acting technique and re-assembling it from the perspective of trainee rather than spectator. In the case of the latter, there have already been several reconstructions of his directorial work which offer an excellent view of Komis’s contribution from the audience’s side of the fire curtain, both at the Barnes Theatre in West London (Tracy 1993; Bartosevich 1992) and, later, at Stratford (Berry 1983; Mullin 1974; Mennen 1979). There is also an extensive and highly scholarly biographical account of Komis conducted by Victor Borovsky and included in his Triptych from the Russian Theatre (Borovsky 2001).

Here the emphasis is different, even though it may at times be exploiting the same sources. In this chapter my aim is to reconstruct the pedagogy which underpinned the creation of those productions, insofar as this is possible. What follows, then, is perhaps best described as a piece of informed speculation using eye-witness accounts, actors’ testimony, the snippets of training ideas inscribed in his three completed books and archival sources such as correspondence and lecture plans. All of these sources will be organised in pursuit of a simple question: what would Komisarjevsky’s projected book on acting have looked like?

There are several reasons why this is a question worth asking: first, it promises to help uncover some of the pragmatics of Komis’s contribution to the British theatre tradition, revealing his directorial successes in a different light and going some way to explaining how those successes were realised; second, it offers an alternative window onto a pivotal period in British theatre history, a period when nineteenth-century traditions of training based on ideas of restraint and individuality were giving way to European models of authenticity and ensemble; and third, it places in a different context statements made by many of the most notable British actors of the pre-war period concerning the craft of acting.

In sum, such a question should help offer a perspective on the pre-war British theatre tradition in transition, a period which Michael Billington describes in his excellent biography of one of those notable actors, Peggy Ashcroft, whose own career was very significantly ‘entwined’ with Komisarjevsky’s, as we shall see later:

[Peggy] talked engrossingly about the “family” of actors, directors and designers with whom her career has often been entwined: John Gielgud, Edith Evans, George Devine, Michael Redgrave, Anthony Quayle, Alec Guinness, Komisarjevsky, Michel St-Denis, Glen Byam Shaw, Motley … I began to understand the continuity that is part of the strength of British theatre: particularly the way in which from 1930 to 1968 a group of like-minded friends and associates created a classical tradition before the big institutions arrived. Even a single-minded visionary like Peter Hall was, in his foundation of the RSC, in many ways giving a practical form to dreams that had been entertained before him.

(Billington 1988: 5)

Komisarjevsky was, for a period of some fifteen years, at the very centre of that family and, as such, must be seen as a pivotal figure in the important developments which ensued and which characterised the establishment, later in the last century, of many of ‘the big institutions’ – the National Theatre, the RSC and the Royal Court, to name three.

Background

Given the patchy evidence of Komisarjevsky’s teaching, it should be instructive to outline, before any detailed analysis, the context within which the Russian émigré was working and to highlight the key historical moments in his career that have direct relevance to questions of training.

The name Komisarjevsky was in fact an anglicised version of his Russian name, Fyodor Fyodorovich Komissarzhevsky, and his patronymic – the middle name taken from his father – is an indicator of a lofty theatrical inheritance. He was the son of Fyodor Petrovich Komissarzhevsky (Stanislavsky’s opera teacher and co-founder of the Society of Art and Literature), and the half-brother of V...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: the mechanics of tradition making

- 1. A tradition in transition: Komisarjevsky’s seduction of the British theatre

- 2. Stanislavsky’s passage into the British conservatoire

- 3. Michael Chekhov and the Studio in Dartington: the remembering of a tradition

- 4. Riding the waves: uncovering biomechanics in Britain

- 5. ‘Who is Skivvy?’: the Russian influence on Theatre Workshop

- 6. Shared Utopias?: Alan Lyddiard, Lev Dodin and the Northern Stage Ensemble

- 7. Re-visioned directions: Stanislavsky in the twenty-first century

- Conclusion: a common theatre history? The Russian tradition in Britain today: Declan Donnellan, Katie Mitchell and Michael Boyd

- Index