Chapter 1

Introduction

Architecture for rapid change and scarce resources

If the nation is destroyed and people’s homes are wiped out, then where can one flee for safety? If you care anything about your personal security, you should first of all pray for order and tranquility throughout the four quarters of the land, should you not?

(Nichiren, Japanese Buddhist monk, Major Writings, vol. 1, 16 July 1260)

On 10 April 2011, upon returning from work, I found that there was no electricity and, consequently, as a pump is used to feed water into our apartment block, there was no water either. I had become used to having both water and electricity all the time in London, despite having experienced shortages in both while living in India. I was feeling a bit smug because I had not been using a fridge or a freezer for almost two years1 and so there was no food that would go off on this hot spring day. I could not use my computer, the Internet or telephone and I do not own a TV. So I turned on my solar radio and relaxed for a while. But then, I realised that I would not be able to cook because the hob uses an electrical spark to light the gas. I could water the plants with stored rainwater but would not be able to drink water myself. My supply of stored drinking water was running out and the shops were out of bottled water owing to local panic buying. The lease rules do not allow the use of fuel-based appliances such as barbecues or a ‘storm kettle’. The electricity was eventually restored after two-and-a-half hours, just as I was thinking of going further to get food and water.

These two-and-a-half hours gave me a glimpse of a future and perhaps an ever-present reality for many of the world’s poor. Despite progress in a technological sense, billions of people remain unfed, homeless or are dying of preventable diseases. According to Wateraid, 884 million people all over the world lack access to a safe water supply and 2.6 billion have no access to sanitation in 2011. They estimate that 4,000 children die daily from diarrhoea owing to lack of clean water and sanitation facilities.2

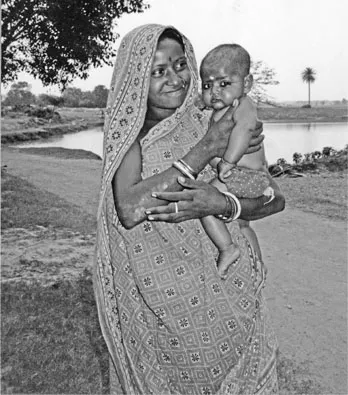

The Millennium Eco-system Assessment, prepared by 1,300 scientists from 95 countries, concluded in 2005 that the excessive exploitation of natural resources would be a cause of future poverty and hunger – not a solution. Now, one in five people live on less than one dollar a day ($1.25 according to some).3 Everyday, one in five of the world’s population goes hungry while in richer countries, people are dying of obesity-related diseases. Half of deaths of children under five are associated with malnutrition (some six million annually worldwide). Some progress, indeed. As I write this, Britain, apparently the seventh largest economy and the home of the Industrial Revolution, is in the midst of a ‘double dip’ recession after just 300 years of industrialization. Its former colony, India, is now the third largest economy (while paradoxically, having the world’s largest number of poor). However, we often find the paradox that the poor are happier than the rich (Figure 1.1). Amartya Sen, the eminent economist notes: ‘Economic growth can make a very large contribution to improving people’s lives; but single-minded emphasis on growth has limitations that need to be clearly understood’.4

Figure 1.1 Proud mother from my village in West Bengal, India. Indeed my English husband remarked that he had seen the biggest smiles in this little remote village with no proper roads, water and electricity. For more on this paradox, see clinical psychologist Oliver James’ book Affluenza (Vermilion, 2007).

Photo: James Jordan.

We look at the practical impact of economic issues on the development activist’s work in Chapter 2.

Architecture for scarcity

All these words – architecture, rapid, change, scarce and resources – are loaded with meanings that differ from time to time, place to place and culture to culture. Architecture is linked to our senses and social communication – a development of visual and cultural identities. It is an essential element in our spatial language using forms and voids, embedded within complex fields of urban and cultural discourses and specific context. Architectural practice today is a complex arena – ever changing and ever expanding. The idea of ‘pure architecture’ is perhaps a futile term – reductive and stagnant. In a lecture at the University of Westminster, the architect Ian Ritchie argued that the shift from an industrial reductivist to a post-industrial holistic approach required a complex enquiry that needs to instigate the social, political and philosophical criticism of design, ‘if we are to re-define our work with any intelligent sense of value and meaning’.5 Questions about the future of architects and the direction of their work are being raised all the time. The Building Design Magazine6 reported that Michael Gove, the British Education Secretary, had told the then President of the Royal Institute of British Architects, Ruth Reed, that there were ‘too many architects’. The Royal Society of Arts organized a competition in 2011 called ‘The Resourceful Architect’ in response to the intriguing questions about ‘architects’ ingenuity, strategic thinking and social role’. As jobs for life and patronage decline, architects have to reeducate themselves in the world of rapid change and scarce resources and create their own meaningful work. This aspect is discussed more extensively in Chapter 9. The nature of participatory work along with the clients and beneficiaries, which is increasingly becoming an important tool of design for the development activist, is described in Chapter 6 (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 MA Architecture of Rapid Change and Scarce Resources students presenting their work to stakeholders in the ‘real world’ at a crit, November 2008, London Metropolitan University.

Photo: Author.

A quarter of the world’s armed conflicts of recent years have involved a struggle for natural resources of one kind or the other. Scarcity of resources and rapid change started in earnest with the Industrial Revolution. As the Industrial Revolution spread around the world, raw materials were taken not only from industrialized countries but also from non-industrialized colonies. Thus, the legacy of the Industrial Revolution – scarce resources – is to be found in most countries, not just the economically backward countries or former colonies. The topic of scarcity in many forms is to be found in popular discussion today. The University of Westminster organized a series of lectures in 2011 called ‘Scarcity exchanges’ bringing together ‘leading international thinkers to expound on one of the most pressing, but often avoided, issues of the day’. Our world is also a very unequal place and this inequality exists not only globally, but also within countries and people. This presents a dilemma that is not only linked to scarcity but also to cultural differences.

Climate change is part of the rapid change of our environment and society. Famines and water shortage, particularly those flamed by climate change and wars, are on the rise. This means that people are also on the move, because they need food and water; and to escape from danger. Petrol is reportedly the reason for wars and invasions now while food is used as a weapon of choice in conflicts by either restricting or withholding it. Demand in Europe and America for gold, diamonds and coltan (mineral used for making mobile phones and computers) from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has claimed an estimated three million lives since 1998.7 Armies of Rwanda, Zimbabwe and Uganda have also plundered DRC’s mineral wealth.8 Water is another source of conflict, rapidly taking over from petrol, probably as it is absolutely essential to human survival. Some of the bitterest issues in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict stem from water allocation and use. According to Amnesty International, Israelis are supposed to be using four times as much water as the Palestinians (I saw many restrictions in place for water use imposed on the Palestinians for farming, sanitation and drinking during my visit there in 20119).

Unfair trade restrictions are also a reason for strange paradoxes. While in the European Union (EU), owing to agricultural subsidies, farmers are literally paid not to farm; the African and Asian countries are struggling with food shortages. Every European cow is subsidized by $2.50 a day, that is 75 per cent more than most Africans live on. The EU is also importing food into Asia and Africa that can be grown locally. As another example, the EU practice of importing sugar has caused world sugar prices to fall by 17 per cent.10 The EU even imports beet sugar to Mozambique, where sugar is a lucrative export crop. The rise of Fairtrade practices since the 1970s is trying to stem this tide of inequality but it has a long way to go, given that the richer nations have already made huge economic headway. For the development activist, Fairtrade is very important because it supports community and social well-being in the form of construction of schools, centres and other buildings in poor countries.

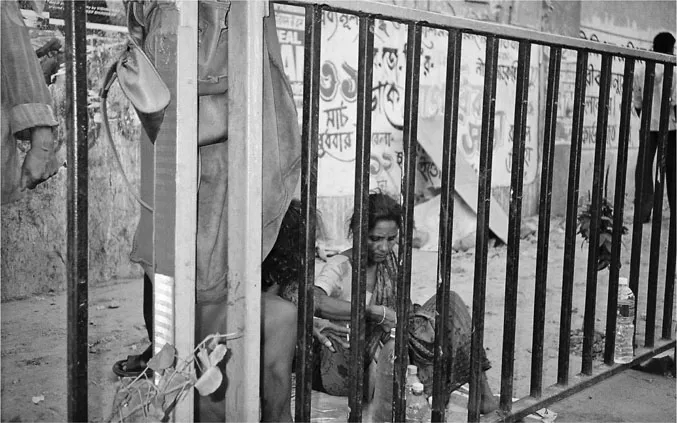

Today, the world’s richest 1 per cent receives as much income as the poorest 57 per cent.11 And of course, it is the world’s richest that commission architects to design their homes, not the ones that are homeless. It is very difficult to estimate the numbers of homeless people in the world because countries have different legal definitions for homelessness. Natural disasters and civil unrest, where people move between places and countries, also complicate the picture of homelessness around the world. The best we have is a conservative estimate from the United Nations in 2005, which puts the number of homeless at 100 million. However, the UN report looked only at people who did not have any homes whatsoever. Not included were people who lived in poor quality housing such as slums and squatter settlements, or people who are on the move. Urban population growth has led to a DIY mentality where the poor moving into the city have taken possession of vacant land and buildings, even streets (Figure 1.3). They build their own homes using whatever materials they can purchase or find. We look at the complex issues of homelessness, squatter settlements and slums in Chapter 3.

Figure 1.3 New migrants to Kolkata, India, from Bangladesh, living on the streets.

Photo: Author.

Studying these areas of rapid change and scarce resources also presents problems of documentation. The ways to observe and record such fragile, varied and dense settlements, composed of people who may be immigrants, and are vulnerable, illiterate and mostly poor, can be a challenging task for those who have been versed in studying formal settlements and order (Figure 1.4). Informal settlements, refugee camps and slums present a chaotic visual experience that can be difficult to put down as drawings. In Chapter 8, I list the ways that my students, colleagues and I have used to observe and record participatively, along with examples of good and bad practices.

Figure 1.4 Old Delhi, once praised by foreign travellers for its beauty and cleanliness, now an urban mess, through past colonial policies, commercialization, overcrowding and insensitive planning.

Photo: Author.

Urbanization and globalization of architecture

Ninety per cent of ancient Greeks lived in the countryside, but the ‘polis’ or the city defined how they lived and interacted. In 1800, only 2 per cent of the world’s population was urbanized. In 1950, only 30 per cent of the world population was urban. In 2000, 47 per cent of the world population was urban. By 2030, it is expected that 60 per cent of the world population will live in urban areas. Venezuela is one of the countries that has already crossed this mark – 92 per cent of its population already live in urban centres. São Paolo, for example, grew 72 times its size in one decade until 2000. The phenomenon of the megacity where the population is more than 10 million is a relatively new development, which has not been seen before. Architects and planners are struggling to understand huge conurbations such as Tokyo-Yokohama (33 million) and Mexico city (22 million). Many of these cities also have densities not seen before – Mumbai, for example, with 20,482 persons per square kilometre (India has eighteen of the world’s fifty densest urban conurbations12). Most of this urbanization happens without infrastructural support – without any water, electricity or sanitation in place (Figure 1.5). People who live in squatter settlements and slums in the poor nations improvise much of these. High densities, poverty and lack of facilities can be responsible for high crime rates – Juarez, in Mexico, is now the murder capital of the world (my visit there, even in 1995, was not easy tourism). Most planned cities are dependent upon the car and oil – and food. A city’s food footprint can be more tha...