This is a test

- 344 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

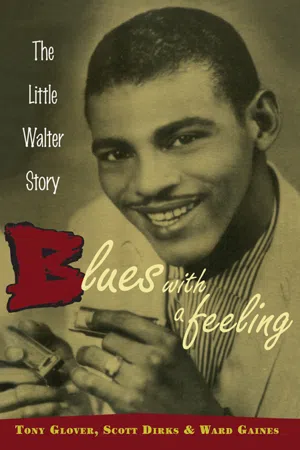

About This Book

Whenever you hear the prevalent wailing blues harmonica in commercials, film soundtracks or at a blues club, you are experiencing the legacy of the master harmonica player, Little Walter. Immensely popular in his lifetime, Little Walter had fourteen Top 10 hits on the R&B charts, and he was also the first Chicago blues musician to play at the Apollo. Ray Charles and B.B. King, great blues artists in their own right, were honored to sit in with his band. However, at the age of 37, he lay in a pauper's grave in Chicago. This book will tell the story of a man whose music, life and struggles continue to resonate to this day.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Blues with a Feeling by Tony Glover, Scott Dirks, Ward Gaines in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Night Train

Louisiana 1920–43

The true circumstances of Little Walter’s early life—of his birth, his family, and his upbringing—are cloaked in deep layers of myth and thick mists of time, more than for any other blues musician who reached his level of fame and prominence in the second half of the 20th century. Details and hard facts seem slippery shape–shifters that vary with each telling—and teller—and pervasive auras of southern-gothic darkness and secrets untold underlie all.

Still, some unassailable facts have been established. He was born in Marksville, Louisiana, some 140 miles north and west of New Orleans in east central Louisiana, in Avoyelles Parish, along the northern edge of an area known as “Cajun country.” Marksville is about 30 miles from the Mississippi River, and within easy driving distance, even in the early days, of the delta area that spawned so many blues greats. Theres very little to differentiate this part of the countryside from that of Mississippi to the east, other than the Cajun and Creole influence most evident in the French names borne by so many streets, rivers, lakes, and other geographic features. The town itself marks the approximate northern apex of a triangle that extends south to encompass the Louisiana Gulf–Coast and everything in between, thus defining the boundaries of Cajun influence in Louisiana.

The nearest “big city” is Alexandria, about 30 miles to the north, in an area now touted by the local tourist board as “The Crossroads,” and also advertised as a part of the state where “you’ll find the hills and bayous, the prairie and the rich Red River Delta, each with its own history and traditions,” as well as “opportunities for fishing, hunting and camping.” Conspicuously absent from the tourist board literature—at least from the perspective of the music fan—is any reference to Little Walter, the area’s most famous blues son, or to the areas Cajun and Creole musical traditions.

The area is also mentioned as the locale for an early traditional “devil at the crossroads” story—the legendary pact wherein a musician reputedly gains his musical prowess by making a deal with the devil. Writer Michael Tisserand quotes Mary Thomas, who grew up around Lake Charles:

There was a four corner road out there in Marksville, and a man told my daddy, if you come here and you wait for twelve o’clock with a black cat, it was selling your soul to the devil… He went and there at twelve o’clock stood the tallest man he had ever seen in his life, with red, red eyes—and every time his mouth opened all he could see was red. And he didn’t ask him anything—he just told him “Play a waltz.” Five minutes later, he was gone, and that cat had disappeared … And the next morning when he started up, he played the accordion, the violin, the harmonica, guitar, bass guitar. Anything he put his hands on[,] he could play …

Although today it’s a small city with a population nearing 6000, in the 1920s Marksville was a “one horse town,” consisting of a center square and a small five-or six-block downtown area that catered mostly to the needs of the surrounding farms and the people who worked them. As in many rural towns in this part of Louisiana, white “Cajuns” (descendants of the Acadians who migrated south from Nova Scotia in the early 1800s) have lived side-by-side with mixed-race “Creoles” (descendants of Black slaves, many from the West Indies) for generations. They’ve shared the same French-based Creole patois, the same Roman Catholic religion, the same food, the same music, and they have celebrated the same holidays. It wasn’t uncommon for them to sometimes even share the same lineage, if one looks back past the layers of southern respectability to the heritage of the original Louisiana Creole culture of the 18th century. There was a long-observed (although seldom spoken–of-in-polite-company tradition) of the white man with his secretive “left-handed marriage” to a black or mixed race mistress, which often lasted throughout his lifetime. This came originally out of a cultural acceptance and even respect given a white man of a higher social status keeping and supporting an “octoroon” mistress in “French” Louisiana despite the legal strictures of the day. Mulattos became part of an “elite” freeman class among other blacks, called “gens libre de couleur.” Out of this heritage, some of their descendants today still retain a bit of this Creole “snobbery.” Author Nick Spitzer points out that both Creoles and Cajuns spoke a mixed and broad French Creole, “using French words within a Creole grammar that came from a variety of African tongues, which probably arose in the plantations of the West Indies.” Spitzer writes, “To be of mixed blood or mulatto carried greater social status than pure African ancestry. The term Creole may have come from persons claiming their European ancestry, and from an attempt to distinguish descendants of French culture from the English-speaking Americans.” However, in the mid-19th century, the term “Creole” commonly meant “a person of French or Spanish ancestry, who may or may not be of mixed blood.”

Early in 1920, census takers made the rounds down the lanes of Marksville, and on January 30th of that year, they visited the farm of Louis Leviege on Duprines Road. Among those the officials registered there that day were the parents-to-be of the man who would change forever the role of the harmonica in blues music. At the time, Little Walter s grandparents, Louis, 42, and his 36-year-old, blue-eyed wife Canelia, had eight children living on the farm that he was still working to pay off. Both of Louis’s parents had been born in Louisiana; his father was said to be “negro and Indian, came from New Orleans,” according to Walter s older sister Lillian, while his mother was white. Canelia’s mother “came from France and was all French.” Both were listed as being English speakers, able to read and write, although Louis reportedly was more at ease communicating in Creole, speaking English only when visitors came.

In 1920, the eight Leviege children ranged in age from 2 ½ to 18 years, with five daughters and three sons (see chapter appendix). Also enumerated in the household that day was a boarder, 22-year-old Adam (better known as Bruce) Jacobs, listed as literate, and a “farm laborer.” Adam was darker but shared some of the same facial features his future son would inherit: high cheekbones and narrow chin, but with a thinner face that matched his rather slight build.

It probably came as a surprise to no one that Adam would kindle a romantic connection with one of his boss’s daughters. At any rate, it’s unlikely that Adam Jacobs was there because he couldn’t find anywhere else to stay in Marksville: he had family throughout the area. In reality, in those days Marksville could almost have been called “Jacobsville”: the 1920 census shows some 24 separate Jacobs households, mostly “farmers” or “laborers,” but also including a Reverend Wallace Jacobs, and his seven sons. Many of the Jacobs were loosely related (some referring to themselves using the Creole pronunciation “Yocko”), but there was also another group that also bore the name “Jacobs” that claimed ancestral roots in Jamaica.

A couple of days after visiting the Louis Leviege household, the census takers recorded Adams parents living in one of the two main sections where Jacobs congregated along Island Road, not far from Choctaw Bayou and about 5 miles west of town. Like the Levieges, 59-year-old Joseph Jacobs and his 25-year-old second wife Elizabeth also worked a mortgaged farm, and lived there with six children (see chapter appendix). There were also at least three other brothers and sisters of Adam Jacobs living in the vicinity in their own homes, all listed as being in their early to mid-20s.

But there were a couple of things the census takers definitely weren’t informed about. According to records found on file in Avoyelles Parish, on February 22, 1919, patriarch Louis and his boarder Adam had gone to the courthouse and applied for a marriage license between Adam and Louis’s second oldest daughter, Cecille. The men filled out the regular forms including one that bonded Adam (as principal) and Louis (as security) to pay $100 to the governor of Louisiana. This was apparently a form of breech-of-promise insurance, because the form continued: “… the condition of the above obligation is such that if there should be no legal impediments to this alliance then said obligation to be null and void.” A license was duly issued for the marriage of the 22-year-old Adam and 16-year-old Cecille. Five days later the wedding took place, officiated over by a Catholic priest and attended by a couple of Louis’s nephews and two other witnesses.

But clearly Adam had a roving eye; the second item omitted in the census report was that about nine months after the wedding, in November of 1919, a daughter, Lillian, was born to Adam—and his wife’s older sister, Beatrice. Beatrice was a slender but busty young woman with thick wavy hair, coffee–with–cream complexion, and high, wide cheekbones that tapered down to a narrow chin, all of which evidenced her French Creole roots. It’s easy to imagine that she might have been considered quite a catch for any young suitor—and just as easy to see where Walter got his fine-featured good looks.

Was the marriage of Adam and Cecille already over when the census takers came around a couple of months after Lillian’s birth? Or was it just that the family considered the tangled relationships private family business, and not the government’s affair? It’s hard to say, but as one of the younger relatives later put it, “I knew something happened; they kept great secrets as well as they could.” Lillian was the first of three children Adam and Beatrice would have together over the next decade, despite an apparently continuing, on–and–off relationship between Adam and Cecille. A few years later, on Christmas Eve (c. 1926) along came John; “He looked like my mother, brownskinned, had curly hair like her,” Lillian said. Sometime around the turn of the decade, Adam and Beatrice had a final falling out, probably a result of the infidelities in which he reportedly engaged throughout his life. (It was whispered that he had eyes for the mother-in-law as well, and some suggested that he was “trying to go through the whole family.”) Whatever the reasons for the split, daughter Beatrice was again pregnant and on her own. The rather strict Levieges considered her a compromised woman.

Louis Leviege and his wife eventually had three more children; Samuel was born a month after the enumerators came through, then younger sister Rita, and finally Carlton, born around 1930. Sam remembered his father as “… a beautiful dad, maybe has a first grade education, but [he] was a family man, loved his family and was a good provider.” Under his hard work, the farm grew to some 40 or 50 acres, including some 25 acres of swamp land. The main crop was cotton. “As far as you could see was cotton, nothing else to raise but cotton,” Sam said. “And we had a great big garden with everything else that was our survival, corn, peas, you name it … I learned how to eat meat, possum and coon.” There were also chickens, cattle, and hogs that were slaughtered for food. The kids were expected to do chores, Sam remembered: “They didn’t stop you from going to school, but when you got out of school, you went and picked cotton, chopped cotton, and everything else.” Like many of the local creole families, the Levieges were Catholic, and Sam recalled a long walk to the church and the nearby school. “I had relatives living out in the country, they’d come to school in a buggy, black couldn’t ride no bus.” Sam remembered his sister Theresa singing in the choir; “She had a voice like Aretha Franklin.” Sam’s oldest brother Rimsey was quite a baseball player: “If Negroes could’ve been playing in the major leagues—he was a shortstop, made Jackie Robinson look like a rookie.” Unfortunately Rimsey was never able to capitalize on his talent; he was hit and killed by a train after wandering too close to the tracks following a night of hard drinking.

On May 1st, 1930, Beatrice gave birth to her second son, whom she named Marion after his grandmother s father. According to Lillian, he was 10 or 12 years younger than her and wasn’t known as Walter then, and wouldn’t be till later years. (No birth certificates have been found for any of the Jacobs children, and it’s likely that none were issued at the time, a common occurrence with the many home births in the rural south in those days.) Years later while on tour with Walter through the south, Jimmie Lee Robinson, his guitarist and friend from early Chicago days said Walter’s grandfather, introduced as “Papoou,” showed him the place where Walter was born, under a tree outside the family’s house. He was told that Beatrice wasn’t allowed by the family to have the baby in the house because she was “out of wedlock”; she’d permanently separated from Adam at some point during the pregnancy. Walter’s older sister Lillian flatly denies this account, and shows a faded photograph of the cabin where she was born and the one nearby where she says Walter was born. The small one-or two-room “shotgun–shack” style dwellings are made from boards of weathered and fading pine, each with a tin roof and a small front porch. The dirt road connecting the two adjacent houses winds past fields bordered by split–rail fences, and they appear to be in a relatively secluded area: there are no other structures visible in the photo.

Whether he was born in the house or outside of it, Walter’s birth was a harbinger of a difficult life to come, with Beatrice hemorrhaging and sick following her delivery. Hearing reports of Walter’s arrival (and possibly the “under the tree” story), and perhaps fearing for the survival of the mother, Adam showed up three days later, seeking to take both John and the new baby with him over to relatives near Alexandria, some 30 miles away. “My grandfather and them didn’t like my mother, and they told her she couldn’t stay over there with his baby,” Lillian admits. “Even though she had two other kids, people was just crazy. When you separated like that, they didn’t allow you to be back with your husband or nothing … But my mother didn’t want to stay, she wanted to be where her mother was at.” Adam wound up leaving his older son John in Marksville with the Levieges but taking newborn Marion. Lillian wouldn’t see him again until he was 11 years old. Adam carried the baby over to the home of his uncle Samuel Jacobs where the boy would spend most of those years, raised by Samuel and his Aunt Dawn. Samuel may have actually been a blood relative, but it would have mattered little even if he wasn’t. During those times, kinship was a fairly flexible connection; any older person who cared for any child could be considered an uncle or aunt, any abandoned child living with another family might be referred to as a cousin, and so on. Possibly seeking to disguise the boy’s identity from any Levieges who might come looking for him—or maybe just in an effort to completely distance him from that side of his family—Adam and his family dispensed with the name “Marion.” It was at this point that the boy became known as “Walter.”

Adam/Bruce had a reputation as a gifted musician, and undoubtedly there was a fair amount of music around his house. “The man could make that violin cry!” Lillian recalled. Lillians younger stepsister Sylvia recalled, “I heard many people say he could play just about anything you put before him—accordion, guitar, harp.” He also played piano, and there was a sort of informal Jacobs family band. “All his brothers would play music,” his niece Rosa remembers. Her father Shelby played guitar, another brother violin, a sister played organ; “He came from a musical family.” There was also the influence of the radio, which broadcasted a rich variety of regional music, including country music like the popular “Grand Old Opry” show, which could be heard beaming from Nashville throughout the south. Harmonica soloist Deford Bailey, one of the first black musicians to be heard on radio, was a regular on the “Grand Old Opry” from 1926–41. He recorded several sides in 1927, and his train imitation pieces set an early standard for what harp players had to do to be taken seriously. It is unknown whether Walter ever heard him, but Bailey’s playing was so influential and widely imitated that Walter could hardly have escaped hearing someone who had come under Bailey’s spell at some point.

Sometime later, younger brother Sam Leviege left his father’s house. “My sister Cecille didn’t have any children,” Sam recalled, “so she took me. I was just a youngster, she was just like a mother to me. She worked for the rich people; when their kids outgrew their clothes, they give ’em to her and she brought ’em home to me. What they didn’t eat, she brought the cold plate to me.” It seems her estranged husband Adam/Bruce was still coming around. “I remember the night he killed this guy,” Sam recounted:

My sister Cecille and I had left my dad s house, had to go about a quarter mile to her little country home. This guy, a mechanic named Milton, was visiting my dad. He left, cut across the cotton fields and cornfields, coming to my sister s house. Well, Bruce was supposed to have been gone, but he came back and was standing right side the chimney. And he shot—this guy was supposed to be Cecilies boyfriend. I witnessed to the killing. Bruce shot and killed him right there.

Adam ended up in Angola prison, where, according to Sam, he eventually became a guard/trustee. From 1917–92, Angola had no hired guards, using instead trustees picked from those in prison for murdering friends or relatives—usually one-time crimes of passion rather than for profit—as a cost-cutting move. The armed guards were told to shoot to wound only—but that was hard with a shotgun. Jacobs again demonstrated his affinity for firearms when he shot a couple of escaped prisoners during a manhunt that ended in woods near Marksville. Sam left town in 1936 to go to work for the CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps, a Depression-era employment program) and moved on to Shreveport.

Beatrice found consolation over the loss of both her unfaithful lover Adam and baby Marion with a young light-skinned man named Roosevelt Glascock, the son of a black African woman and “a man buried in the white part of the cemetery,” as one daughter put it. According to another daughter, “His daddy was Irish.” Roosevelt’s mixed–white blood didn’t protect him from the violent and organized racism that was prevalent at the time, however. There is a family legend passed down about Roosevelt and his mother having to hide in a mattress because the Klan was after them. Glascock was an educated man—“These mulatto kids was all educated”—in fact his eleventh-grade schooling qualified him to teach public school had he chosen to do so (completing eighth grade was the teaching requirement then). But Glascock had other business on his mind; his biracial background would come in handy as he ran “Dubeau’s Corner” a “black and tan” gambling club, “white on one side, black on the other,” in downtown Marksville right across from the courthouse and the town lock up. Beatrice and Roosevelt soon hooked up, and around 1934 she gave birth to Lula, the first of three daughters they wo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- contents

- acknowledgments

- preface

- 1. night train

- 2. good evenin’ everybody

- 3. wonder harmonica king

- 4. i just keep loving her

- 5. ebony boogie

- 6. “juke”

- 7. diamonds and cadillac cars

- 8. you gonna miss me when i’m gone

- 9. roller coaster

- 10. i’ve had my fun

- 11. crazy mixed up world

- 12. i ain’t broke, i’m badly bent

- 13. back in the alley

- 14. mean old world

- epilogue

- chronological recordings

- sources and notes

- bibliography

- index